The memories are starting to chip a little. Like nail polish on fingers that have plunged too many times into the dishwater or planted too many things into too-hard layers of earth. I do remember, though, that we spoke sometimes with snacks. Eye contact in the rearview mirror or the revelation of a furrowed brow and the inklings of a how much longer? would lead to baggies of Goldfish crackers being passed around as we ticked off mile after mile after mile on our first road trip as a party of three. My son was 7, and my daughter was 5, and I decided that — that summer, at least — we’d be brave.

We went to Southwestern Colorado by way of the Grand Canyon, Navajo National Monument and the Four Corners. We stayed, the three of us, in my two-person backpacking tent, for nights on end, first at the Canyon’s Mather Campground, where we saw an elk that came to drink from the community spigot. He was massive and backlit, and his antlers were draped in velvet. He was mythical. He was real. Even now, years later, he comes up in dinnertime conversations.

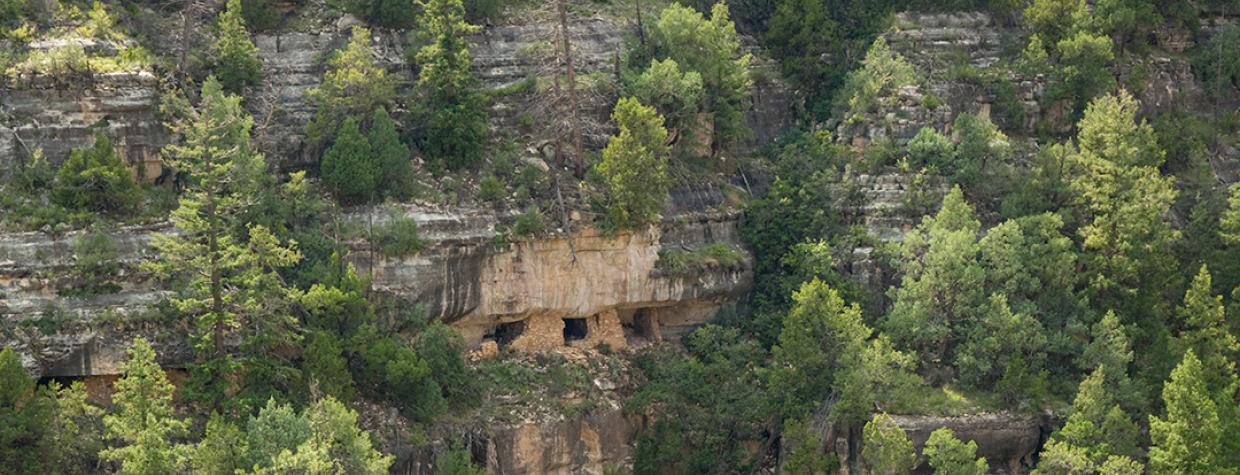

We spent two nights at Mesa Verde National Park in Colorado, where Ancestral Puebloans built intricate dwellings into cliffsides, as if that were something easy. We ate spaghetti that I pre-prepared and stored in gallon-sized Ziploc bags, then heated up in my tiny little propane-powered backpacking pot. We listened to a lot of John Prine.

The kids slept as I was stuck behind a semitruck driving up U.S. Route 550 between Durango and Ouray, Colorado, in wind and driving rain. I left marks on the steering wheel of our rental car that afternoon, terrified that I’d spin out in the water that coated the highway like spilled paint. We probably camped a few more nights after that, but I very clearly remember double beds and a takeout pizza and a plunge in a natural hot spring at a motel in Ouray before we began the slow drive back to Phoenix.

But the drive back didn’t mean we were done. Along the way, we stopped at Petrified Forest National Park and to see that corner made famous by that song that Jackson Browne wrote. And then, we decided to push it, to try to fit in just one more destination, a place none of us had ever been — Walnut Canyon National Monument. The idea? To prove Wallace Stegner’s notion that national parks were America’s best idea — that they show us at our best, rather than our worst.

When the Sinagua people moved into Walnut Canyon more than 1,400 years ago, they farmed squash, corn and beans below its rim. These crops comprise the “Three Sisters,” the nucleus of Indigenous culinary heritage. Although Walnut Creek twists for 34 miles along the Colorado Plateau, from the canyon it cut east of Flagstaff to the tiny town of Winona (which once was called Walnut, too), it is unreliable and often dry.

Sinagua. Sin agua. Without water.

And so, the people used dry-farming practices to make it all work, gathering rainwater from terraces built into the canyon walls. As their techniques evolved and the years ticked on, so too did the way the people lived. Pit houses along the rim evolved to alcoves beneath it. Archaeologists tells us that women were in charge of the architecture and the construction of their families’ homes. They used clay as mortar to seal cracks in the limestone rocks that formed the walls. They turned logs from felled trees into doors. The alcoves were advanced, but the Sinaguans lived in them for only a little more than a century before they moved on. Hundreds of years later, 232 prehistoric sites would be folded into the national monument that now pays tribute to the ancient people. Hisatsinom. The people who came before.

Of course, explaining all of this to two children at the tail end of a too-long road trip wasn’t easy. But there was something about the Island Trail that they liked. As we hiked the mile-long loop, they asked a lot of questions and imagined themselves living there, largely outside, eating the Three Sisters crops, as well as nuts, wild berries and hunted meat. We named some of the plants and trees — the ones that I knew from memory, anyway: ponderosa pine, Arizona black walnut, yucca, a columbine or two that peeked from the canyon walls. The others, we promised to research when we got home.

As we made our way back to the visitors center, I remembered a story that ran in the November 2010 issue of Arizona Highways. It was about writer Willa Cather visiting Walnut Canyon while on leave from her editing duties at McClure’s magazine. Cather was trying to find inspiration for a book,

so she signed in as “Miss Cather” on the visitor register on May 23, 1912, just months after Arizona became a state.

There’s more to the story, of course, but according to the author of the 2010 article, Jane Barnes: “As it turned out, it was the place where she became known to herself. At Walnut Canyon, Cather finally found her own center. She was surrounded by civilization, but free from its demands. She was alone in a great space, but the cliff dwellers had domesticated it so she did not feel overwhelmed.”

Cather’s resulting novel, The Song of the Lark, drew heavily from her experience in Walnut Canyon. She called it by another name, though: Panther Canyon.

“That sounds … scarier,” the kids agreed as we loaded back into the car.

I think that my children were too young to find their centers at Walnut Canyon that day, and they’ve probably long forgotten the story of Willa Cather, but whatever intuition comes with carrying two children and traveling with them years later tells me that they found something there in the wonder of it all. The expanse of it. The impossibility of building homes from canyon walls and truly, truly living off the land.

In the five years since that first big road trip, we have traveled thousands of miles across the western United States. We’ve seen a bald eagle fly over the Columbia River Gorge. We (briefly) lost our car keys in a fast-moving creek somewhere in Idaho. We rode out a thunderstorm in a leaky tent in rural Montana. We found ourselves high-centered in our getting-too-small Subaru at an abandoned campground somewhere in the Sierra Nevada, dug ourselves out, then found a better campsite along the Pacific Crest Trail. We have seen Glacier National Park in the morning light and later in a drizzle. We have run, diving into our tents, to save ourselves from swarms of mosquitoes somewhere in Northern California.

We have been — in alternating cadence — at our best and at our worst on these trips.

Just days after I finish this story, we’ll load into the car again for three weeks. There are four of us now. A dog, too, who wears her bandana like a badge. The kids sleep in their own tents. And we’ve graduated from bagged spaghetti to red beans and rice cooked in cast iron over coals. Little things change. Big things change. The excitement doesn’t. And while there aren’t any national parks or monuments on our list this year, we never know. Sometimes our roads dead-end. And sometimes that means that the next turn will be better.

No matter what, though, I think I’d like to take the kids back to Walnut Canyon when we get back. Just the three of us. To see what they’ll remember. And what new magic they might find.

(For Jack and Vera, Summer 2021)