SO, HERE'S MY BIGFOOT STORY.

On the last night of a llama trek in California’s Sierra Nevada, we camped somewhere around 8,000 feet. It had been an eventful trip: creeks swollen by snowmelt, a near-drowning and frequent sit-down strikes by the llamas. (They’re adorable, but not for six days at a stretch.) We finished the box wine, its terroir and vintage of equally dubious provenance, and gorged on the remaining food, ostensibly to lighten the llamas’ load for the last push back to the trailhead.

Around 3 a.m., I heard a sound coming from the meadow where the llamas pastured for the night. Still in my sleeping bag, I pulled open the tent flap and saw a shadowy, human-like figure waving its upraised arms and running through the campsite while screaming an ungodly scream. Elevation and cheap wine will play tricks on the mind, and there was enough time in that realm between dreams and consciousness to think the unthinkable.

It’s the big guy! Sasquatch, Bigfoot, the mythical cryptid of bumper stickers and rear window decals come to life. Or, in this case, my hirsute friend Tom. Half-asleep and stark naked, he had rushed out to help the wrangler scare a black bear away from the llamas.

For those few hazy seconds, I believed. And as I sit here now, brain-fog-free in the light of day, I cannot claim that a latter-day Gigantopithecus walks among us. However, that strange night did lead me to ponder the concept. Consider me Bigfoot-curious.

Which brings us to the Mogollon Monster, Arizona’s homegrown Bigfoot variant. He’s tall and hairy, smells of soggy dog and rotten eggs, and almost certainly doesn’t exist. But easy as it is to dismiss accounts of massive ape-like creatures as so much codswallop and hokum, these tales cross history, cultures and geography.

Start with the giant swamp-dwelling monster Grendel in Beowulf, the Old English epic poem possibly written as early as the eighth century and the bane of high school students 1,300 years later. The Mogollon Monster has kinfolk across America, including New York’s Kinderhook Creature and Appalachia’s regrettably named Wood Booger. In Australia, Bigfoot is the Yowie, and in Mexico, it’s the Sisimite or El Cuatlacas.

“It’s really interesting that they’re humanoid, but usually larger and stronger than us,” says Arizona State University literature instructor Dr. Emily Zarka, an expert in monsters who created and hosts the PBS Digital Studios series Monstrum. “They can be protectors of the environment they inhabit, and maybe even help humans. But they can also be aggressive and defend their territory.

“I think that these legends are in part about our ancestry and understanding of what human evolutions look like. It’s about fearing that we’re not on top of the food chain — whether it’s an unknown cryptid being that could be more powerful than us, or the misidentification of some kind of species that may or may not be extinct.”

In a time before shares and likes and all things viral, the Mogollon Monster legend spread not like wildfire, but through the slow burn of old-fashioned storytelling around campfires.

The monster doesn’t appear to pop up by name in newspapers until a 1967 article about a Boy Scout camping trip in the White Mountains. The article provides no context for what the Mogollon Monster actually is, but the big fella is mentioned matter-of-factly, as if readers already know all about him. “Some of the boys even claimed to have seen it,” according to the article.

The Scouting connection is strong. In an online account titled Bigfoot at Tonto Creek, the late cryptozoologist Don Davis recounted attending Scout camp in the early 1940s at the base of the Mogollon Rim outside Payson. While hiking, Davis and a friend raced ahead of their group and spotted “a reddish-brown figure” walking “with a strange sort of rocking motion.”

After they set up camp, odd things began to happen. One boy reported that someone had stolen the fish he’d just caught, and the scoutmaster worried a stranger might be lurking nearby.

That night, Davis moved his sleeping bag away from the group to find comfortable ground free of tree roots. He later heard rustling and footsteps. He recounted: “There, standing less than 4 feet in front of me, was a monster-like man. (Please note that I did not say a man-like monster.) The creature was huge. … His chest, shoulders and arms were massive, especially the upper arms — easily upwards of 6 inches in diameter, perhaps much, much more.”

Looking deeper into the legend’s origins, it becomes clear that the Mogollon Monster wasn’t the spawn of the Atomic Age fascination with mutant beasts that made Godzilla, Mothra and the Creature From the Black Lagoon the subjects of endless schoolyard debates. It predates early cryptid-inspired cinema, such as The Wolf Man and King Kong, by decades and goes back to a time not only before movies and television, but also before radio and Arizona statehood.

In the late 19th century, so-called “wild men” were all the rage. The Tombstone Daily Nugget published an 1881 account from the improbably named Julius Starlight, who claimed to have seen “a singular object” that “bore some resemblance to a human being … whose entire body appeared to be covered with hair.” Prescott’s Weekly Arizona Miner mentioned a wild man in the Hualapai Mountains in 1882, and the same year, the Tucson Citizen published an account of a creature in that range who raided miners’ cabins and was held “in mortal terror” by local Indigenous people.

Similar wild man stories were common throughout the American West. In his 1889 book The Wilderness Hunter, none other than Theodore Roosevelt described an encounter in Montana between a grizzled hunter named Bauman and a Bigfoot-like beast. Bauman and his trapping partner returned to their camp and discovered something had destroyed the site. Based on the tracks, the creature walked on two legs and was neither bear nor human. Before the spooked men left the valley, Bauman checked the beaver traps one final time, then came to find his friend dead with a broken neck and four fang wounds in the throat.

The Mogollon Monster’s urtext appeared in The Williams News on May 23, 1903. Below the masthead depicting ponderosa pines and mountains, a headline read, “Wild Man in Grand Canyon: A Colorado Man Tells Thrilling Story of Adventure With Strange Creature.” (Talk about clickbait.)

I.W. Stevens of Cedar, Colorado, then described a recent beaver hunt during which he came upon footprints presumably left by a Paiute or Hualapai man. Two days later, Stevens spotted someone on the north side of the Colorado River: “I saw sitting on a large bowlder a man with long white hair and a matted beard that reached to his knees. … He wore no clothing, and upon his talon-like fingers were claws at least 2 inches long. A coat of gray hair nearly covered his body, with here and there a spot of dirty skin showing.”

Brandishing a large club, the wild man charged at Stevens, who raised his rifle to defend himself. But Stevens also noticed a mountain lion, with two cubs and ready to pounce on the wild man, and fired a shot, mortally wounding the lion. The wild man then killed the orphaned cubs and “drank the warm blood as it flowed from the death wounds. The sight sickened me,” Stevens said, before fairly concluding, “That was the strangest adventure of my life.”

If lacking the Q rating of saguaros and Gila monsters, the Mogollon Monster is today more loved than loathed, and an effective Arizona brand ambassador.

After moving to Arizona in the early 2000s, brothers Noah and Jeremy Dougherty got serious about hiking and running. While competing in a historic 50-mile endurance run named for Zane Grey, they discovered the Mogollon Rim. “It wasn’t what we were used to in Arizona,” Noah says. “There were ferns and beautiful lakes and mountains, and views for days without being muddled up with telephone lines and towns.”

After deciding to start their own race, the Doughertys traveled to The Rim to map a course and began to hear stories about the monster from locals. And considering that the brothers were launching a 100-mile beast of a race — one ranging up to elevations of 8,000 feet, with grades as steep as 45 degrees and 18,000 feet of climbing — “Mogollon Monster” was a perfect name. Plus, it makes for one heck of a first-place trophy.

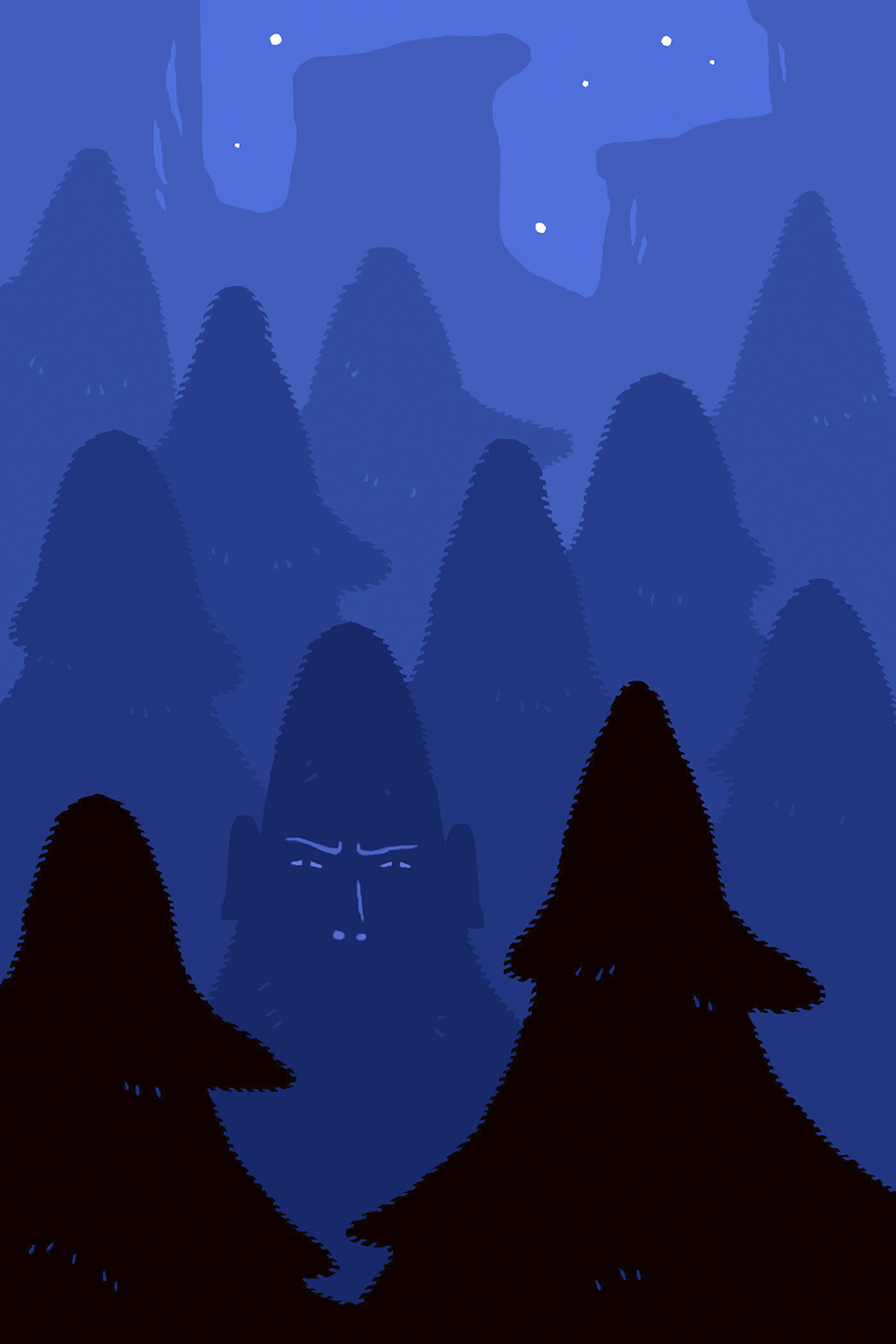

For the record, no runner has actually spotted the monster, and Noah says, “It’s hard to wrap your head around the monster being a real real thing.” But plant the idea of a hairy humanoid in the imaginations of sleep-deprived runners, all by themselves in a dark forest while racing for more than

30 hours, and just about anything seems possible.

“When my brother and I ran in 2017, this woman came up to us around 40 miles in,” Noah says. “It’s pitch black, and she’s like, ‘Can I run with you guys through the night? Because I just don’t want to be out here alone and run into something.’ Yeah, people do get freaked out.”

I increasingly wondered about connections between the Mogollon Monster and Navajo belief, especially after a friend sent me a 1944 book about the Wide Ruins Trading Post. I randomly opened to this passage: “The belief in the werewolf is a common and ancient one with the Navajos — the belief in a human wolf, in a man disguised in animal skins who goes about at night practicing witchcraft.”

The Navajo creation story about a powerful, violent monster named Ye’iitsoh also suggests a Bigfoot-like creature. Ye’iitsoh figures prominently in the AMC series Dark Winds (which is set on the Navajo Nation), and in his 2024 book

The Paranormal Ranger: A Navajo Investigator’s Search for the Unexplained, Stanley Milford Jr. describes multiple Bigfoot incidents, including in the Chuska Mountains and near Chinle.

In his Dragnet-meets-CSI: Sasquatch style, Milford details his own encounters. While convinced Bigfoot exists, Milford questions why he never found habitations or remains, such as bones, when bears and mountain lions leave such physical evidence behind. He also marvels at Bigfoot’s ability to suddenly vanish.

Milford cites Navajo creation stories that “include different worlds, different layers of existence, planes of being besides our own” before reaching a conclusion: “I had watched it disappear with my own eyes. So, I had to conclude that … it had stepped out of another dimension and into our world. And then it stepped back out.”

Idaho State University anatomy and anthropology professor Jeffrey Meldrum, a leading advocate for Bigfoot’s existence, discovered the creature’s cultural prominence in the Southwest while appearing at a conference at the University of New Mexico-Gallup. During a four-hour talking circle, Meldrum listened as the predominantly Navajo crowd shared firsthand stories and perspectives on Bigfoot’s ties to their traditions. “In Western culture, we make a strong distinction between empiricism and mythology,” he says. “Whereas in the Indigenous world, it’s kind of a seamless transition from one into the other.”

As a fifth-grader in Spokane, Washington, Meldrum attended a screening of the famous Bigfoot film made by Roger Patterson, who, in that pre-YouTube era, barnstormed with the clip. “To see Bigfoot marching across the screen made an indelible impression, to say the least,” Meldrum says.

We cover lots of ground: the challenges inherent in Bigfoot DNA testing, anatomical evidence from footprints Meldrum concludes were left by a relict giant hominin, and changing perspectives on the complexity of the human family tree. Yet definitive proof remains elusive, and Meldrum says such scarcity is the result of Bigfoot’s inherent rarity. “We’re talking about an animal that, by virtue of its natural history, is expected to be low in numbers compared to other forms of wildlife,” he says.

Staking out a position as a Bigfoot believer hardly qualifies as a careerist strategy in academia. Meldrum makes his case with calm clarity, and I’m certainly not qualified to challenge him on non-divergent big toes, geometric morphometric skull analyses and the phylogenetics of fossil hominins. I also realize I’m less interested in proof that the Mogollon Monster exists than in the persistence of the belief.

My buddy Tom, he of the llama trek, died last year. I always told him that based on the colossal mass of his head, his copious pelt and features more chain-sawed than chiseled, he was rocking more than his fair share of Neanderthal DNA. Tom was remarkably well read, but one primal dude and very much from the “We don’t know what we don’t know” school of thought. That inspired his lifetime of adventure. Because sometimes, the knowing isn’t nearly as much fun as the wandering and wondering. Which helps explain why so many people believe the Mogollon Monster could exist.

“As we become more urbanized and more dependent upon technology, I think there’s a real attraction to this idea that there’s still mystery out there,” says Zarka, the monster expert. “And, frankly, that there’s something out there that has managed to remain hidden. Despite all of our modern advances.”