I have klatarismenophobia.

I hadn’t heard of it, either. But it turns out there’s a name for the irrational fear of getting a flat tire. For me, the roots aren’t hard to trace: In the summer of 2019, while researching a book about ghost towns, I punctured a tire on a remote stretch of dirt road in 113-degree heat. I changed the tire and made it to safety, but ever since, I’ve dreaded hearing an unexpected chime and seeing that little orange light on the dashboard.

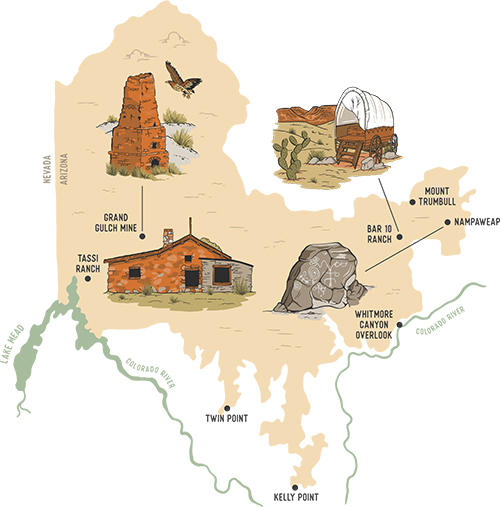

Nevertheless, I’m about to visit a place that eats tires for lunch: Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument, a land of solitude, diverse terrain, dark night skies and incredible views of its namesake gorge and the Arizona Strip. It’s a place I’ve been dying to visit — and a place that, if I’m not careful, will happily oblige.

People were practicing social distancing at Parashant (pronounced PAIR-uh-shont) long before the pandemic made it fashionable. At more than 1 million acres, the monument is nearly as large as Grand Canyon National Park, which sees about 6 million visitors annually. But Parashant gets about 1 percent of that — an estimated 77,000 per year, or about 200 per day. As one of the last truly wild places in the American Southwest, it offers zero cell service and road conditions that range from “rough” to “extremely rough.” A visitor can easily go days without seeing another soul. It might be the worst place in Arizona to get a flat.

My work at Arizona Highways has taken me all over the state, but for years, Parashant has been my white whale: impossibly large, forebodingly inaccessible and begging to be explored. Now, I’ve rented a suitable vehicle and studied the list of provisions I’ll need for a three-day adventure. I’ve planned my route, where I’ll stop and even how much gas I’ll use. In a place like Parashant, such plans aren’t just important — they’re critical to survival.

But as I’ll soon find out, plans at Parashant are a lot like tires at Parashant. They’re subject to change.

Parashant, the landscape, is home to 1.7 billion years of geology and some 13,000 years of human history, but Parashant, the monument, dates only to January 2000, during President Bill Clinton’s administration. It owes its existence to Bruce Babbitt, the former Arizona governor who served as Clinton’s secretary of the interior. Babbitt pushed for the 1906 Antiquities Act, which long had been employed to create and expand sites within the National Park Service system, to also be used to carve national monuments from large swaths of land overseen by the Bureau of Land Management.

Parashant, along with Agua Fria National Monument north of Phoenix, was part of a wave of new monuments that resulted. Joined by Babbitt and other dignitaries, Clinton issued the proclamations creating both monuments during a visit to the remote Toroweap area of the Grand Canyon’s North Rim. Today, Parashant is jointly managed by the BLM and the Park Service; the latter oversees the section closest to the Canyon rim, territory previously managed by Lake Mead National Recreation Area.

Jeff Axel, Parashant’s chief of visitor services, public affairs and partnerships, says the arrangement is unusual among his 10 postings over 25 years at national parks. “It’s really the only one of its kind in the Park Service,” he says, and the BLM partnership was one thing that drew him to Parashant. Another was the splendor of the Strip, which Axel notes “is a beautiful place to be — if you’ve got the right vehicle.”

That’s the other thing that sets Parashant apart. You’d have a hard time finding another park whose website is so devoted to asking: Are you ready for this? Really? Photos abound of passenger cars mired in a foot of mud and SUVs with two wheels removed, and multiple pages are devoted to the vehicles, tires and other equipment visitors need. There are seasonal concerns, too: The monument’s high country, studded with ponderosa pines, gets snowy, icy and muddy in winter, while the desert regions are oppressively hot in summer.

“It’s really about making sure people understand they have to be prepared,” Axel says. “We’ve had fatalities out there. People have gotten stuck or broken down, and without connectivity, nobody knows where they are.” A couple of times a month, someone needs to be rescued — and those are just the situations the monument’s staff knows about. Often, wayward travelers are trying to reach the developed North Rim area and take a wrong turn. “I found somebody, a month or two ago, who was totally freaked out,” Axel says. “They thought they were at the edge of the Earth. And they sort of were.”

Preparing for a trip to the monument (see What You Need To Know, below) is a lot like preparing for a long backcountry hike: Take everything you might need, and assume you won’t have help. “A lot of times, what people expect when they go to a national-park-type area is that there are going to be amenities and there’s going to be somebody coming by who can get them out of trouble,” Axel says. “Here, depending on where you are and the time of year, there might not be somebody coming by for a month.”

But that’s part of what attracts people to Parashant. “You can get to some really quiet places and some wonderful hikes,” Axel says. “It’s that experience of seeing what a lot of the country used to be without as many people as we have today.”

Suitably intrigued and intimidated, I follow Axel’s recommendations to the letter, load up my rented Jeep and head to Kanab, Utah, where I’ll spend a night before dropping into the Strip in pursuit of my white whale.

DAY 1 Kanab, Utah, to Bar 10 Ranch

I set out before dawn and soon find myself on County Road 109, the only reliable road into the east side of the monument. I make a quick side trip to Toroweap Overlook — which is part of Grand Canyon National Park, but I’m not coming all this way and not standing atop a 3,000-foot cliff over the Colorado River. Then, I backtrack and head west on County Road 5, which winds around the pine-covered southern flanks of Mount Trumbull, the centerpiece of one of Parashant’s four wilderness areas.

After only a few miles, I reach the rough, rutted side road that leads through junipers, piñon pines and a few ponderosas to my first stop: Nampaweap, one of the Strip’s largest petroglyph sites. I hike the short, easy trail and soon see dozens of pristine petroglyph panels on basalt outcroppings high above the path. Some of these drawings may be 10,000 years old, and they illustrate this wild place’s extensive human history — which includes the Southern Paiute people, who have ancestral ties to the monument. (The name “Parashant” is derived from a Southern Paiute family name.)

Continuing west on CR 5, I pass through a thick ponderosa stand before reaching the Mount Trumbull Trailhead, where I’ve planned a strenuous 5-mile (round-trip) hike to the monument’s highest point. Starting out in a piñon-juniper forest, I soon am navigating the trail’s punishing switchbacks while crunching over red cinders, evidence of the more recent of two eruptions on this basalt- and cinder-capped mesa. I remind myself to slow down — always a problem for me — and look up, and I’m greeted by an incredible panorama of the Toroweap Valley to the southeast and smaller cinder cones to the south. The climb is a heart-pounder, and I can’t help but think of my dad, who had a heart attack two weeks before my trip and then underwent triple bypass surgery. You know, that stuff is hereditary, the voice in my head tells me. And you’re turning 40 in a week. My response: This isn’t the time for this conversation with myself!

Past the switchbacks, I reach a section of ponderosas that burned in a lightning-caused fire in 2019. From here, the trail gets tough to follow, and I’m route-finding via the crunch of pine needles (too crunchy means I’ve lost the path) when I notice the first in a series of improvised rock cairns. Back on track, I scramble uphill to the U.S. Geological Survey marker, surrounded by old-growth ponderosas, at the peak’s 8,028-foot summit.

From a vantage point near the summit, I can see the Vermilion and Hurricane cliffs and the broad Uinkaret Plateau to the north. It’s a worthy reward, but judging by the register at the summit, it’s one that few have claimed: The most recent entry is from four days ago. On the way back to the Jeep, I wonder: How many people have reached this summit in the past year? How many have ever reached it?

And that’s the Parashant paradox. The trail won’t get more defined without more people to hike it, and more people won’t hike it until it’s easier to follow. Along those lines, the monument’s rough roads discourage people from driving on them, and without much vehicle traffic, improving those roads isn’t a priority. But all of this is a feature, not a bug. “We’re not going to make it an easy experience,” Axel says. “We want folks to have that challenge, and what we find is that visitors want that challenge. They don’t want the ‘groomed’ experience, like you get at other places. They want to get an ATV or a Jeep and say, ‘How far can I get out here?’ ”

Riding an exercise high, I pass the site of Mount Trumbull’s first sawmill, where ponderosa logs were processed for use in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints temple in St. George, Utah, among other projects, starting in the 1870s. It’s a short ramble west from there to the Mount Trumbull Schoolhouse, just outside the monument’s boundaries. The building is a replica of one that opened in 1922, held classes until 1968 and burned down in 2000. Inside, photos and a large relief map tell the stories of Mount Trumbull’s pioneering Mormon families, many members of whom still call the area home and contributed to the rebuild.

Southeast of the schoolhouse, down rough, rutted BLM Road 1045, is the Bar 10 Ranch, which sits on one of several inholdings in the monument. The Bar 10, run by the Heaton family since its inception, is marking 50 years as a cattle ranch this year but also has grown into a lodging destination for Parashant visitors, as well as for Colorado River rafters who arrive via the ranch’s landing strip and helipad.

The Bar 10 is also one of the only places in the monument where you’re likely to see other people. Over a roast beef dinner at the lodge, I meet Frank Lekan, who’s 72 and first came to the ranch in 1990 after an Arizona River Runners rafting trip. “I just thought it was the greatest place,” he says, and he now visits twice a year. The Colorado hooked him, too: Now retired from his job as a UPS driver, he works as a river host and has been on countless rafting trips.

Parashant, Lekan says, “has had a place in my life for a very long time.” Like many visitors, he enjoys tooling around in an ATV and visiting overlooks, including those that aren’t on the Park Service map. “I don’t know how to explain the feeling,” he says, adding that he’s happy “just to be out in the open and be able to go someplace where you don’t have 50 million people.” And the views are unbeatable, especially for a guy whose idea of heaven is “getting up in the morning, making a cup of coffee and seeing the Grand Canyon.” Someday, Lekan hopes, his ashes will be scattered at the monument.

A vintage covered wagon, one of 14 that dot a hillside behind the lodge, is where I’ll spend the night. Bundled up against the nighttime chill and exhausted from a day of driving, I drift off to the sound of a ranch hand strumming a Johnny Cash song at the fire pit.

DAY 2 Bar 10 Ranch to Twin Point

After a hearty breakfast, I continue south on BLM 1045 to the first of two Grand Canyon overlooks I’ll be hitting today. Descending an ancient lava flow into a landscape of creosote, barrel cactuses and prickly pears, I soon reach Whitmore Canyon Overlook, which is 1,000 feet above a broad bend in the Colorado.

This view is unlike any I’ve seen at the Canyon: high enough to take in the enormity of the surrounding buttes, yet low enough to see (with binoculars) the expressions on river rafters’ faces. I spot two rafting camps, one downstream on the north side of the river and one upstream on the south side. As I watch, a helicopter buzzes down the river and lands at the latter camp to pick up a few weary rafters, then flies past the overlook en route to the Bar 10.

I backtrack to the schoolhouse, then follow CR 5 north, along the southern section of the Hurricane Cliffs, to County Road 103, which passes Poverty Knoll and Poverty Mountain on its way back into the monument. These roads are among the best I’ve traveled on this trip, and being able to go 40 mph feels like flying after a day and a half of bumping along. Heading south, I cut through expansive fields of sagebrush before climbing back into the junipers and ponderosas.

My original plan was to continue on CR 103, which later becomes a Park Service road, to Kelly Point, the southernmost overlook in the monument. It juts far into the Canyon, and the view there is legendary. But Axel has talked me out of it: The 31.5-mile road to the overlook is extremely rocky and rutted, and traveling it in a Jeep would take me four to five hours each way. Instead, I navigate the initial stretch of the road to Waring Ranch, where cattle rancher Jonathan Waring settled in the 1920s; by the 1960s, he owned 13,000 acres in the area, making him the Strip’s largest private landowner. Lunching amid junipers, pines and a few decaying buildings, I note that the wind is picking up. I don’t know it yet, but that weather condition will define the rest of my day.

Next, I get a good look at 7,054-foot Mount Dellenbaugh — thought to have been climbed by the three men who abandoned John Wesley Powell’s 1869 expedition down the Colorado, then disappeared — en route to Twin Point, a Canyon overlook northwest of Kelly Point. The road to the overlook is rough but manageable, and I’m anticipating a view that includes the Sanup Plateau just below the point, Burnt and Surprise canyons cutting into the North Rim, and the Hualapai Tribe’s land on the South Rim.

The Canyon, however, has other plans. Arriving around 3 p.m., I’m greeted by 50 mph gusts blasting out of the gorge, which is socked in by a thick layer of dust. Standing near the rim, I feel like a TV weatherman aiming to go viral during a Category 4 hurricane. I can’t even see the South Rim, let alone any landmarks. The cloud cover means stargazing is out, too, and when I set up the Jeep’s rooftop tent, it acts like an unwieldy parasail. With better visibility looking unlikely, I decide to head “inland” and camp in the ponderosas, which should provide a windbreak. If that’s the worst thing to happen on this trip, I think as I head north, that won’t be bad at all.

If only.

DAY 3 Twin Point to Mesquite, Nevada

I awake to frozen rain on the Jeep and spot a few mule deer in a nearby clearing, then break camp and head northwest, toward the Grand Gulch Mine. Axel is meeting me on the side road that leads to the site so he can tell me about the mine’s history. But once I hit a decent road en route to our rendezvous point, I notice a strange shimmy in the Jeep’s steering wheel. I dismiss it as a traction control glitch and make it to Axel without much trouble, and we hop into his truck and start rattling down the rough road that leads to the mine.

Axel has spent the past seven years at Parashant and clearly knows it as well as a person can know a million-acre place. On the 14-mile ride, we discuss everything from the area’s geology to one of the monument’s latest wayward travelers: a motorcyclist who was headed to Kanab and somehow ended up at Kelly Point, then ran out of gas and hiked 30 miles in his motorcycle boots before being rescued. Before long, we’re at Grand Gulch, which sits on a bench of the Grand Wash Cliffs, the Canyon’s western boundary.

A Southern Paiute prospector found copper at this site in the 1870s, and the resulting operation produced 6.6 million pounds of the mineral from unusually high-grade ore, some of it more than 75 percent copper. The mine closed after World War I, although a reprocessing operation in the 1950s briefly gave Grand Gulch new life. Today, the mine shaft is on private land, but visitors can see the powder house, a bunkhouse, a crumbling headquarters building and a smelter that, according to Axel’s research, never worked quite right. Two 1930s-era dump trucks and a rudimentary airstrip are relics of the mine’s short revival. And the views of the surrounding cliffs are as alluring as any I’ve seen on this trip.

Back at the Jeep, we go over the rest of the day’s route. To avoid a deteriorated section of road, we’ll loop far to the north, then head south to Pakoon Springs and Tassi Ranch, two historical sites in the sandy Mojave Desert lowlands of Parashant’s western section. Then, I’ll cross into Nevada and spend the last night of my trip in Mesquite.

But my plans are about to change again. After a few miles, Axel, who’s trailing me, honks and pulls alongside as I again deal with the bucking steering wheel. “I see what’s going on,” he says. “And it’s not good.” We quickly diagnose the problem: The bolt that connects the Jeep’s track bar to the frame has broken or come unscrewed, likely during my return from Twin Point the night before. As a result, the front wheels gyrate wildly when I hit the slightest bump at faster than 15 mph or so. (I won’t learn until later that this is commonly known as a “death wobble,” and that’s probably for the best.)

We assess our options, all of them bad. We don’t have the materials to attempt even a temporary repair. And a 60-mile tow from here to a repair shop could cost thousands. I decide to make an exceptionally slow drive north to St. George along a series of decent dirt roads. “We always say you haven’t been broken in at Parashant until you’ve gotten a flat,” Axel says as we get back into our cars. “You took it a step further!”

The next four hours are the longest of my life: This stretch isn’t particularly scenic, and if I accidentally gain too much speed, I take another ride on the world’s worst mechanical bull. Axel, a true mensch, follows me the entire way, offering encouragement when we stop for breaks. Finally, we crest a hill, the city comes into view, and I get three days’ worth of notifications on my phone. We pull into the shop around 4 p.m. Utah time, and the repair is quick and cheap. But I’m due back in Phoenix tomorrow, and we’ve run out of daylight. Two stops short of its intended conclusion, my adventure in Parashant is over.

The mechanical bull tamed, I bid a grateful farewell to Axel and take Interstate 15 to Mesquite. Tomorrow, I’ll head home to my wife, and my kids, and my dad, and my 40s, and everything else in my life that simultaneously gives me purpose and drives me insane.

Someday, though, I’ll return to Parashant, and I know exactly what I’ll do. I’ll come in from the west, plow through the sand to see the historic buildings at Tassi Ranch and marvel at how ranchers made a life there in the early 20th century. I’ll head from there to Pakoon Springs, flowing freely again after decades of impoundment, and run my hands over the restored vegetation. And then I’ll loop around the Grand Wash Cliffs and back to Twin Point, where I’ll finally see the Canyon the way few others have seen it and fall asleep under a star-filled sky.

Or maybe I won’t. Because a place like Parashant can upend even the best-laid plans. That’s one of the beguiling, spellbinding things about this wild, wonderful place. Another is that it might give you an irrational fear of losing a bolt. I don’t think there’s a name for that.

What You Need To Know

Visiting Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument is an amazing experience, but you need to be prepared. That starts with having a high-clearance, four-wheel-drive vehicle with all-terrain tires — not street tires. The monument also recommends you take two full-size spare tires (or, if you have only one spare, an air compressor and a tire patching kit), along with a jack that will work on a rocky or sandy surface. Side-by-side ATVs are another popular option for traversing Parashant’s rough, unmaintained roads.

If you don’t own such a vehicle, companies in Arizona and Utah offer Jeeps, side-by-sides and other suitable vehicles for rent. For this story, I used Phoenix-based Red Rock Adventure Rentals (602-999-6591, redrockadventurerentals.com), which rented me a Jeep Rubicon (pictured) with a reserve gas tank and a rooftop tent. Other than the unlucky lost bolt, the car performed well at the monument.

Other things to pack include more food and water than you think you’ll need, a shovel to smooth cut banks or dig out of sand, and clothing for a wide range of temperatures and weather. There’s no cellphone service, so GPS devices, satellite phones and messengers, and apps such as Avenza Maps — which allows you to orient yourself on pre-downloaded maps, even without cell service — can be extremely helpful. Even if you have these tools, leave a detailed itinerary with someone who knows when to expect you back.

The only lodging option in the monument is the Bar 10 Ranch (435-628-4010, bar10.com), which offers rooms and covered wagons, along with hot showers and hot meals. Gas is available for purchase, but only by Bar 10 guests; there is no public internet access, but there is a satellite phone available for a fee. Elsewhere at Parashant are primitive campsites along roads and at overlooks. Rangers ask that you respect Leave No Trace principles by using existing sites, rather than creating your own.

Most importantly, contact the monument (435-688-3200, nps.gov/para) before your trip to get the latest road conditions and weather forecasts, discuss your plans and confirm that you have everything you might need. Parashant is truly wild country, and you alone are responsible for ensuring your safety and survival. Devoting enough time to preparation will make that task much easier.