ON A LATE-SUMMER DAY IN 1929, all manner of visitors came to Bright Angel Lodge, the rustic hotel perched on the South Rim of the Grand Canyon. A pair of rangers sat boldly, dangling their cowboy-booted feet, on the fence that separated a sidewalk from the Canyon’s fatally deep drop. Parents strolled by with a tight grip on their children, gawking at the grandeur.

One visitor stood out. She was tall, her snow-white hair tied up in a hasty bun. Her laced-up black boots were dusty from use, and her skin had the weather-worn look of someone who spent a lot of time outdoors. But it wasn’t her appearance that caught the eye. She stood out, in fact, because she was standing very still. Her gaze was fixed not on the vast splendor of the Canyon, but on a currant bush that grew just beyond the fence.

She made a low, coaxing whistle: pit-r-ick, pit-r-ick, pit-r-ick. In response, a yellowish-green head popped out of the bush and into the sudden illumination of a sunbeam. The woman spoke softly; after a moment, the immature western tanager came out of the bush to perch brashly on the fence, almost within arm’s reach. The bird had a berry in its beak and a certain head tilt that suggested to the white-haired woman a look of “winsome trustfulness.”

The woman’s name was Florence Merriam Bailey, and she had just turned 66 — “a husky old dame,” in her own words, “yet fit for the fray.” She had spent four months at the Canyon, hiking its trails, camping along Bright Angel and Pipe creeks, and keenly observing the birds.

Bailey was a rarity among ornithologists: female, self-trained, and a college dropout with a quiet way of ignoring the norms of her profession. It was common at the time to look at birds through the sight of a hunting rifle — skinned specimens were the way to go. Bailey had other ideas.

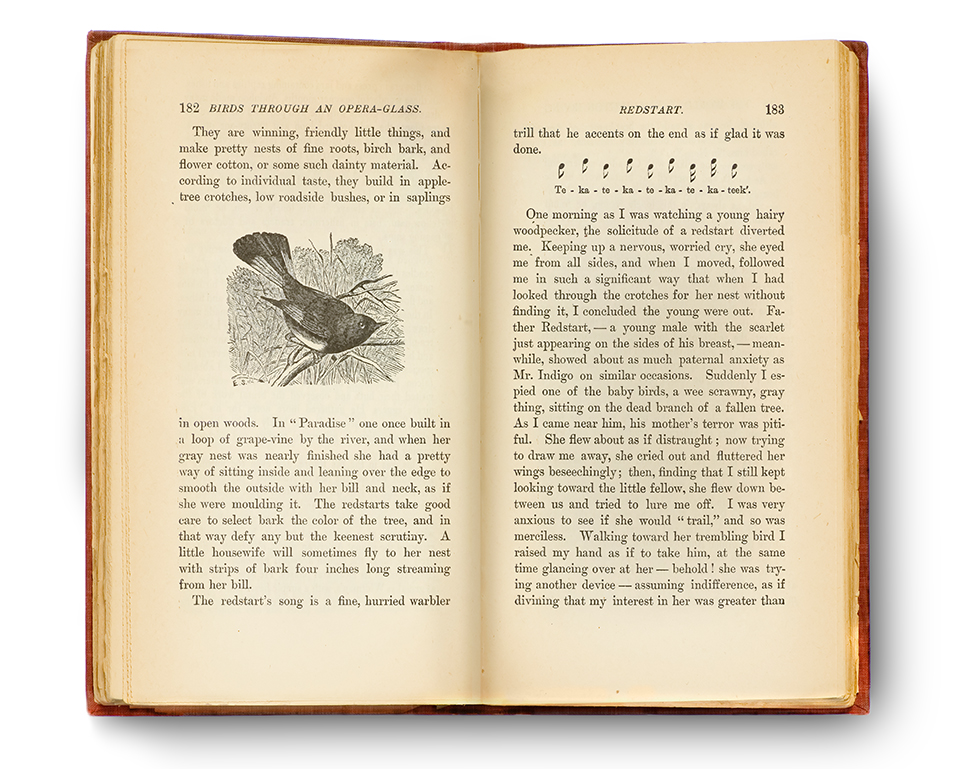

“Make a practice of stopping often and standing perfectly still,” she advised in her 1889 book, Birds Through an Opera-Glass. “The best way of all is to select a good place and sit there quietly for several hours, to see what will come.”

That advice might seem prosaic to birders and birdwatchers today, but not in Bailey’s era. She had been born to a wealthy, well-connected family in upstate New York in 1863. And although she would adhere all her life to the mores of the Victorian Era — soft voice, ramrod-straight posture, calm demeanor — she had escaped the notion that a woman’s role was confined to the domestic. Or, rather, her idea of “the domestic” encompassed a wide, wild world.

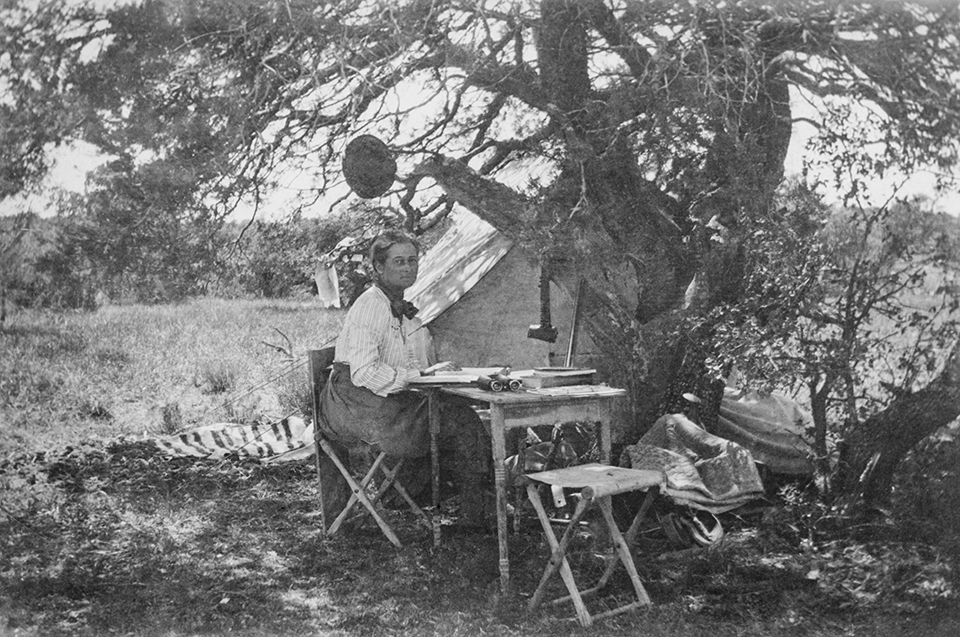

She traveled West for the first time in 1889, at age 25, for the sake of her health. Bailey suffered from an illness she never named; her biographer Harriet Kofalk called it “the great shadow.” This shadow, likely tuberculosis, didn’t stop Bailey from preferring sleep “with the heavens for a roof,” as she put it, over the comfort of a bed indoors. She wore divided skirts to explore the countryside by horseback and bicycle, and long before sleeping bags were stocked at stores, she invented a water-resistant bedroll by coating sheets in beeswax.

She was 36, a spinster by the reckoning of her era, when she married a fellow scientist and explorer, Vernon Bailey. He was a field naturalist at the U.S. Bureau of Biological Survey, the forerunner of the Fish and Wildlife Service. The couple hosted elegant dinner parties at their home in Washington, D.C., but anyone brave enough to peep beyond the dining room would be startled by the sight of a live lizard basking in the library — and, upon further exploration, might chance upon a hibernating bat in the pocket of an old sweater.

Bailey’s habit of welcoming unconventional houseguests didn’t stop when she traveled, and at the Canyon, she raised the ire of a hotel maid by sharing her room with a pregnant horned toad that soon produced 18 babies. Birds, however, were her chief delight, and not just the rare and unusual. On the Canyon’s rim, she wondered at the ravens circling far below her feet. “What was the game?” she wrote. “Were they toying with the air currents? As I watched in amusement, from deep down below they would let the morning upcurrent lift them to the height that pleased them, then break away, circle about, fly down, and drift up again like children at play. Sometimes at the lowest point of their descent I could not tell them from their shadows laid on the ground by the rising sun.”

Bailey rode a mule down the South Kaibab Trail, feeling herself “a least speck in that vast abyss,” and spent two weeks camping at Bright Angel Creek, where she recorded every sighting, rare or commonplace, with equal pleasure: the kingbird beating a scorpion to death, the mourning doves congregating in the mule corral, the “kaleidoscopic flock” of violet-green swallows that split the evening sky. One day, she spied an American dipper standing on a stone in the rushing creek. “So brave,” she gushed, “so cheery, such an exuberant songster.”

Her language might seem quaint — today, scientists frown upon ascribing human characteristics to animals. But Bailey lived in a time when birds were being shot in droves by farmers protecting their crops, hunters procuring feathers for fashionable hats, and ornithologists who believed the only way to properly identify a bird was to kill and skin it.

Consider the 1879 book American Ornithology, which suggested making a soft whew-whew whistle to American wigeons “to entice them within gunshot.” Or the 1892 Key to North American Birds, which devoted its first eight pages to advice about guns and ammunition. The author, Elliott Coues, suggested collecting 50 to 100 specimens for every species of bird, admitting freely, “Your humanity will be continually shocked with the havoc you work.”

Bailey’s own brother, the famous naturalist C. Hart Merriam, had shot and killed a flammulated owl in the Canyon in 1889. That was the gorge’s only record of the soup-can-sized owl until Bailey, sans shotgun, spotted a live one on her trip 40 years later. She never quibbled with the need to shoot birds for scientific collections; she simply set about doing science a different way. “The fact of the matter is,” she wrote in A-Birding on a Bronco, “you can identify perhaps 90 percent of the birds you see with an opera-glass and patience.” As for the remaining 10 percent, she mused, “Could I take their lives to gratify my curiosity about a name?”

Coues sneered at the “opera-glass fiends,” but Bailey’s lively writing soon found an enthusiastic following. Any newspaper running a column on bird life was apt to quote “Mrs. Bailey” as the authority on the matter. Her popular books replaced scientific jargon with elegant prose and precise illustrations; they’re often considered the first birding field guides.

Bailey used her platform to raise concerns about the threats diminishing bird populations, many of which still feel relevant. She worried about feral cats, window strikes and car collisions, collectively still responsible for millions of bird deaths every year. And she was active in the movement to end the use of feathers in millinery.

But while she frequently expressed sorrow and indignation over the deaths of birds at the hands of “thoughtless or prejudiced man,” her writing was full of joy. For Bailey, to be outdoors was to be “in the heart of things,” and to while away an afternoon watching birds was her best, truest purpose. Among the 180,000-plus people who visited the Canyon in 1929, she must have been the only one to think the scenery second-best. She couldn’t help haranguing tourists (“whose overfed minds,” she wrote, “can take in no more views”) to pay attention to the birds.

“They were more important to me than I to them,” she admitted, “going calmly about their affairs, paying little heed to meetings that I took much pleasure in.” But that was the point, after all: to study birds without harming, scaring or startling them. Opera glasses not only brought birds into reach; they suggested a new kind of attitude in the nascent art of birdwatching, one that considered a bird’s behavior equally important as its anatomy or plumage.

Bailey’s writings show a keen understanding of how birds fit into their environment — what she called the “home life” of birds. She observed their mating habits, parenting techniques and differing styles of song. She pulled apart old nests and counted every feather. Long before science communication was a buzzword, she sought to humanize birds, depicting them as music makers, homebuilders, capable of great migrations and devoted to their families.

Lingering at Phantom Ranch, at the bottom of the Canyon, one day, Bailey watched a pair of ash-throated flycatchers search for a suitable nest. The birds oscillated indecisively between a too-small bird box at the top of the dining hall and a roomier one in the crook of a cottonwood tree sheltering the grounds.

Bailey waited, her eyes on the soon-to-be mother bird. “She stood with the wad of material in her bill, wings drooping, merely looking around,” she wrote. “He kept calling; she, perching. The kitchen door slammed, the gardener hosed the yard. It was a good place for flies. ... But how about the black hunter cat addicted to catching and playing with lizards?”

When the flycatchers finally settled on the cottonwood, Bailey watched the nest construction with concern and pestered the park rangers to add a tin collar to the tree to keep away the hungry house cat. They ignored her request, so it was with relief that Bailey heard some weeks later that the pair of flycatchers had successfully raised their chicks — and even more relief when she learned a few years later that Grand Canyon National Park had banned cats and dogs below the rim. The park might have been established for its spectacular vistas and jaw-dropping geology, but to Bailey, its most important role was the “friendly protection” it offered to birds.

Among the Birds in the Grand Canyon Country, published in 1939, was Bailey’s last book. She died at home in Washington in 1948, at age 85. Her death went largely unnoted by newspapers, but some years later, a writer memorialized her: “On that day there departed a true friend of birds, a sweet and unselfish spirit, and altogether a most unusual woman.” She was remembered as the first female fellow (a contradictory title) to be elected to the American Ornithological Union.

In 2023, that organization, now the American Ornithological Society, began revising English common bird names that honor people, such as the Clark’s nutcracker and the Cooper’s hawk, in response to calls for inclusion and social justice. The change will ultimately affect 263 birds in North and South America, but Bailey isn’t among the historical figures whose names will be sponged from the field guides; she was never there in the first place. The closest she came to recognition of that kind is the Latin name of a subspecies of mountain chickadee, Poecile gambeli ssp. baileyae — which, to date, remains unchanged.

Birders and birdwatchers around the world now adopt the practices Bailey championed, studying birds in their own habitats without disturbing them. But few now know the name of the ornithologist who, at the bottom of the Grand Canyon and in wilds throughout the American West, perfected the art of “stopping often and standing perfectly still.”