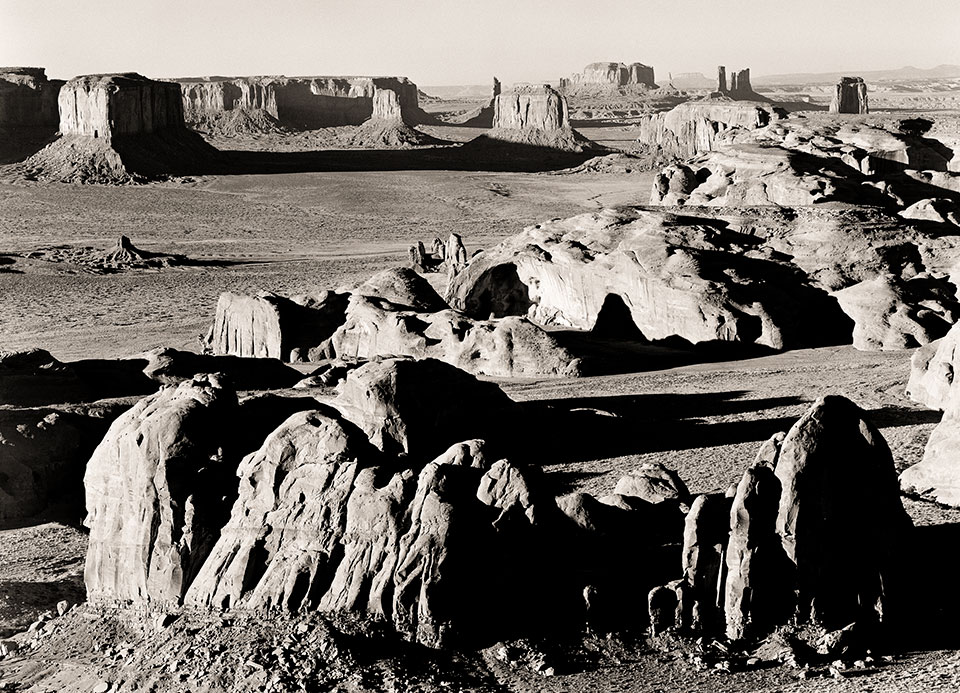

It was dawn in Monument Valley. From out of utter darkness, as still as it was complete, was born a sight never to be erased from the colored slides that our memory holds sacred. As a pale light appeared, it etched in tender grays, a magic skyline of shapes. Then before the mind could fully grasp their nature, they darkened, until for a brief moment they were etched in black, jagged, irregular, varying monuments in stone. That was over before long and the sun, swinging into its full power, put to flight the pink of the clouds and the whole desert came ablaze. While the eager eye was chasing across the landscape from point to point with wonder, the scene dulled a little. The earth settled down, shrank into itself, as though withdrawing from its too vital creator. The pageant of day had begun again in Monument Valley.

We stood on the porch of one of the little cabins at Goulding’s Trading Post in Utah. This small settlement clings to the side of a great sandstone mesa, tucked into a nook high above the ample floor of the valley. Here the Indians come for their flour and coffee and candy. They bring their blankets and rugs to sell and their jewelry to pawn. When they ride up on their ponies they are visiting one of the most removed spots in the United States. It is 190 miles from any railroad! The nearest standard gauge railroads are the main line of the Santa Fe which goes through Flagstaff, and the Denver and Rio Grande, through Thompson, Utah. But in the comfortable living room of the lodge, crowded with Indian rugs and with pictures of the area, civilization does not seem far away.

And certainly adventure lies at one’s doorstep, for Monument Valley waits. No hour of the day is without interest if one can take the time to stand and look out at those monuments that rise grandly from their rocky bases, miles and miles across the valley.

Busy little man has looked upon them and named these rocks, with titles that are often a trifle absurd. But they serve as handles in describing what one sees. To the left on this striking skyline is “Pop’s Mesa,” a long stretch of unadulterated mass; flat on the top and impenetrable. It sheets off at either end and looks vast and mysterious. It, with its fellows, rises on an average of from 800 to 1,200 feet from the ground. No wonder they bulk so against the distant haze of the morning. “The King’s Tomb” is next, and is fittingly named. With his back to it is “The King on his Throne.” There is a rigid back of a chair and the imagination has no difficulty in investing the erect figure that sits there, with kinghood. Looking from another direction the next two monuments become “The Castle” with crenelated top. The “Bear and the Rabbit” can be made out and next to them “The Fingers.” The clenched hand has several fingers straightened out, pointing to high heaven. The scene ends with “Brigham’s Tomb.” Almost any of these monuments might be called tombs. In the morning light they are unspeakably somber and heavy.

But no one watching all of this will be content to stay up on the hill. The road which drops with the terrain, down to the horizon of the monuments, invites. It is a narrow, sandy road that crosses first the main road from Kayenta, Arizona, to Bluff, Utah. Then it climbs straight toward the rocky statues.

“Pop’s Mesa” loses its straight shape as one approaches it and becomes a fortress with wings on either side. They seem to sweep toward one, wings of fretted sandstone. Then one great portion of the pile becomes a huge red elephant charging down upon the hapless occupants of the approaching car.

Having reached the end of the first rise one feels as though now he was about to really enter a valley. For, having their bases in this lower land, the great panorama of buttes, of which those seen from the distance form only a small portion, rides serenely into view. There is something very theatrical about the arrangement and the posture of many of them. Take the triumvirate of the two “Mittens” and of “Merritt [sic] Butte.” The mittens are mates, the left and right being set so that the wearer, if his hands be of the proper size, might reach out and put them on. The left “Mitten” is three miles from the vantage point, the right, six miles. Each is set on a perfectly balanced base, gradually tapering up to where the mitten itself sits solidly. “Merritt Butte” is farther on to the right, beautifully smoothed and fluted on its sides, a gem of a monument. The soft pastel shades of the sand, the occasional greenery, and the blue to purple distances touch the landscape with the blending shades of skillful water-coloring.

Now for a time the road itself must occupy the driver as well as any other occupants of the car. It is apt to be a little uncertain, and it is always of great interest. Its base is sand. The base of all things here is sand. Man has bolstered the way here, filled it out there, guarded its curves as best he might. But sand is temperamental and the weather has its own way with that frivolous substance. The road looks different in some detail, if not in more than that, almost every time that one drives upon it.

Now the road curves and dips and takes itself right down into the valley. The red sand, which from a distance is apt to take on other colors, becomes a covering and a background color that seems to touch all things on the landscape with its own basic shades. Up through it the sturdy desert plants emerge. There are various species of cactus and sagebrush, blackbrush, greasewood, rabbit-brush, shadscale and yucca.

One of the most majestic sights in the world is to be had by taking one of the side roads from the main one. (If one may speak thus of any of the roads in the valley.) It curves gently through a tiny pass and then treats the visitors to one of those breathtaking views of line and color that seems to arrest time, so vivid is it. Let me paint in a few of the high points. To the left, the usual mesa frames the picture and to the right, horizontal lines run from the periphery of vision. Everything draws the eyes to the center. There, highlighted, is a small (from where we stand) group of monuments. It is “Yebechai” or the Twelve Dancers, named after the most sacred and secret of the Navajo ceremonial dances. Sand dunes tie this group to other ones beyond. The “Pioneer Woman” looms in the distance. Then a purplish haze fills out the background. Fleeting clouds add interest to the sky and its blue is accentuated by the red stone and the red sand. Some master of line has been at work here. The air is thrillingly quiet. Not a sign of human life mars the landscape. The roadway — two tracks — is so soon lost in the dust that they form no part of the vision that the eye and the heart see.

To leave mere gazing and approach the Yebechai, one travels the faint tracks around more monuments. The slender threads where men have gone before drop down around precarious curves and then take off boldly through a stream, follow its bed for a while and then go up an impossible hill as though mounting to the very sky. Not all cars can follow, and not at all seasons can any go there. So let us take to foot, up over the dune, for “Yebechai” lies ahead. On top of the red dune another surprising world awaits one. It is as though the wind has wiped the earth off clean and made it shining and new. The road and its approach are lost, the winding river bed just crossed is forgotten, too. Only in the distance looms the “Totem Pole,” highest of the Twelve Dancers. If the wind be awake and in pursuit, then the trip over the dunes will be accompanied by sharp discomfort, for the red sand bites. On one high place, the remnants of flints have been found. Here was once a city, long since completely obliterated by the sand, for it was caught in a river of it. Here and there a plant has caught a foothold in the sand and makes a small spot of color that stands out from the reddish dust.

Now we stand at the foot of the “Totem Pole.” One thousand and six feet [sic] this incredible rock projects itself. In one spot it narrows and then widens again at the top. Down its sides are cuts which give it the look of having been carved. It might well have been meant for the totem pole in Alaska of some Indian from that far clime. Here it has a graciousness that is not entirely describable.

Not far from here is another group of monuments which never fails to excite the imagination. It is called “The Three Sisters” and there, walking in single file are three figures, drawn with a precision amusing when the height concerned is close to a thousand feet. A large shapeless mesa might be acceptable as the cathedral toward which these pious figures move their steps. The first figure is heavy set, perhaps an older sister. Behind her, head bent and wearing a long veil is the small figure of a novice. Behind her is the prioress, with hands folded in front and eyes downcast. The whole dominates the landscape and is reverently done. Truly an amazing feat of nature.

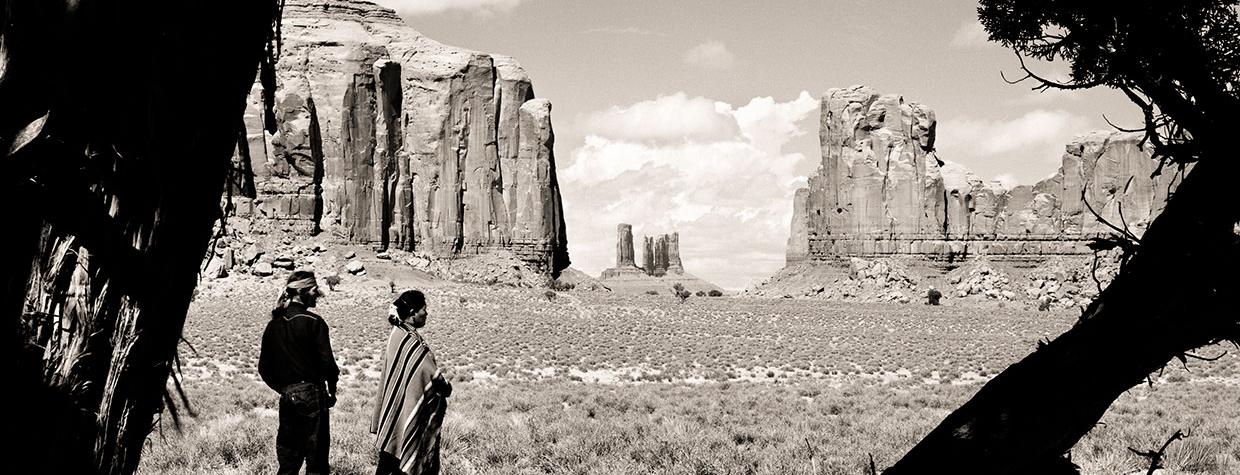

It was while we were enjoying this view that we were made aware of a Navajo riding along a far horizon. He had appeared from nowhere and as silently disappeared behind one of the endless dips in the land. Rugged, calm as the monoliths, he accepts nature with the same kind of unquestioning resignation.

The natives seem unaware of the monuments, and apparently beyond naming some of them, they do not concern themselves over their origin or strange shapes.

On a summer day when storm clouds grow in a moment, and continually play back and forth, the many vistas offer unending variety. Sometimes one sees an etching in stark, bold lines, which can change momentarily to the softest of water colors, or the richness of oils, with the sun highlighting now this rock and now that.

The fading afternoon light touches things with its softening effect as we make our way back to Goulding’s. High above the tiny patch that we know to be the Trading Post, stand the “Sentinel” and “Baldy,” guarding “The Gap” which opens a small but interesting region that has a stone bridge and picturesque side-canyons and ridges.

Again from our vantage point of the cabin, sunset takes us by surprise. Then again, great beauty comes to the watcher from the porch. The monuments themselves take on the pinks and purples that the sun ordains and all is translated into a fairy scene that is full of lightness and fancy. The scene gradually fades and finally, darkness drops like a mantle and blots out everything.

No one can see Monument Valley, unless perhaps, he be an Indian, without wondering how it came to be. Surely no ordinary forces were at work here. It has been studied only a little by geologists and not very completely surveyed. But its history can be traced in general by a study of the rocks. Some of them are of marine origin and some of continental. Evidently there was a great river running through part of a tremendous plateau. It is responsible for tearing out great layers of the softer deposits and leaving these sections which were more resistant. The deposits of rock are as great as 2,300 feet thick on some places. It was through this that time and the seasons wore, making a valley. It is cut up so that there are literally hundreds of valleys within the one, and so will prove of interest to geologists for some time to come before its story has been unravelled in detail.

In this country where rocks predominate, one can almost forget man and his place in the order of things. But even here that small but persistent creature deserves a page or two. For man has lived in the valley farther back than can be accurately estimated. On the walls of a protected butte in a particular canyon that lies beyond endless bends and dips in the ruts, is the earliest known mark of the Indian. Some antelope chase each other across the soft curve of stone. There is no mistaking what they are, crude though the drawings appear to our more sophisticated eyes. Nearby several flute players seem to be serenading a lady. Who knows how many more such sketches there once were before nature washed them off with her eraser of wind and water? It has been a long time since there was water enough to sustain life for such wild folk as the antelope. Yet the record shows that they were once here and that the Indians were familiar with them.

Pioneering white men and women saw the valley as they pushed west for gold or new homesteads. The miner and the ruthless frontiersman who took whatever he saw came to the valley. In the late eighties two such men noticed the silver that the Indians used for ornamentation, for belts, and rings, buttons and horse gear. After a time they even located a mine in the vicinity. The Indians believe that to dig into the earth is to hurt their great mother and they do it reluctantly and fearfully. They say that she will punish them by sending evil spirits to take their land away from them. Anyone who stops to think what would happen if gold or silver were discovered in any amounts in these desert lands, will agree that the Indian superstition is not without foundation. But it had been so easy the first time, that they came again the next year with a wagon and more adequate tools. They loaded the wagon with as much silver ore as they could take away and started across the valley.

It was midsummer and the rainy season was imminent. Clouds brooded over the horizon and touched some of the monuments. Mother Nature was in a quarrelsome mood. There was something in the air that set the nerves on edge. The wagon was almost out of the valley, and soon the buttes would fall behind them as they pushed on steadily toward Kayenta and civilization. Then the storm broke. Added to the clamor of the wind and the roar of thunder, came Indian voices and the rapid thud of Indian ponies’ hooves. Before the brigands could get out their guns one of them was dead. The other man grabbed the reins from his partner’s hands; saw the limp body hit the ground. He whipped the horses to their best speed, and for a while seemed to be widening the space between himself and his pursuers. He pulled out from the shadow of the butte where his dead comrade lay and his horses plunged on. When they came opposite to another butte, almost two miles away, a shot finished him, too. Those two buttes bear the names of the unwise fortune seekers who died at their bases, Merritt [sic], and Mitchell. The Navajos say that it was Paiutes that did the killing. The Paiutes say nothing.

It is mostly Navajos who live in the valley now. We visited one of their encampments and watched one of the women at her sewing. The family was seated in the shade of a cottonwood tree. Household goods were suspended from the branches. Pans, blankets, horse gear, ropes, an empty shortening can, a flour sack, a pair of handmade moccasins, a tanned goat skin could be seen. On the ground were more things strewn about in careless profusion. A skin was pegged to the ground and almost completely covered with dirt.

The young woman at the loom was unusually handsome. Her fine long fingers worked with the ease of long practice and she had time to spare for frequent timid looks in our direction. Her mother sat nearby, carding wool for the rug, and her daughter, a child of about seven years, was helping.

The father of the family was working a hide. He braced himself against the tree and was using his foot to stretch it out. With the help of the Indian Trader we carried on a conversation with the family. A bag of candy did much to create a friendly atmosphere, for the Indians of all ages are very fond of candy.

The Navajo was amused at the short hiking trousers that my husband wore. “See,” he said, pulling up his trouser leg and revealing a bare leg, “I am poor too. I wear no socks.”

Living a life almost of destitution, there was still room for a joke, for friendly talk, as they worked for a sack of flour and some coffee to add to their diet of mutton and corn.

Monument Valley might well have been erected as a memorial to this brave race which struggles on against conditions which we would deem impossible, and yet can laugh.

Beautiful Monument Valley, terrible Monument Valley. But for us there need be only the beauty since we can go there and breathe in the atmosphere of ageless serenity and then go back to our own smaller domains where labor yields us the nourishment of body and soul that we require.

The narrow sand road will widen and its capricious sand will be tamed by modern road builders. Then there will pour into its uneven terrain the flood of people who travel in search of the new and exciting. Go now and see it while you can still run the risk of spending an extra half hour in pulling out of a sandy spot in the road. Go while there is still time to spend the day there without a sign of human life other than the Indian, who is part and parcel of the scenery.