Tucked away in the shadow of the rugged Bradshaw Mountains, not far from Lake Pleasant, Castle Hot Springs once boasted a dazzling guest list — from Rockefellers to Carnegies to a Kennedy. Yet for 40 years, the resort sat empty, frequented only by a caretaker and countless owners whose grand plans for the site fizzled.

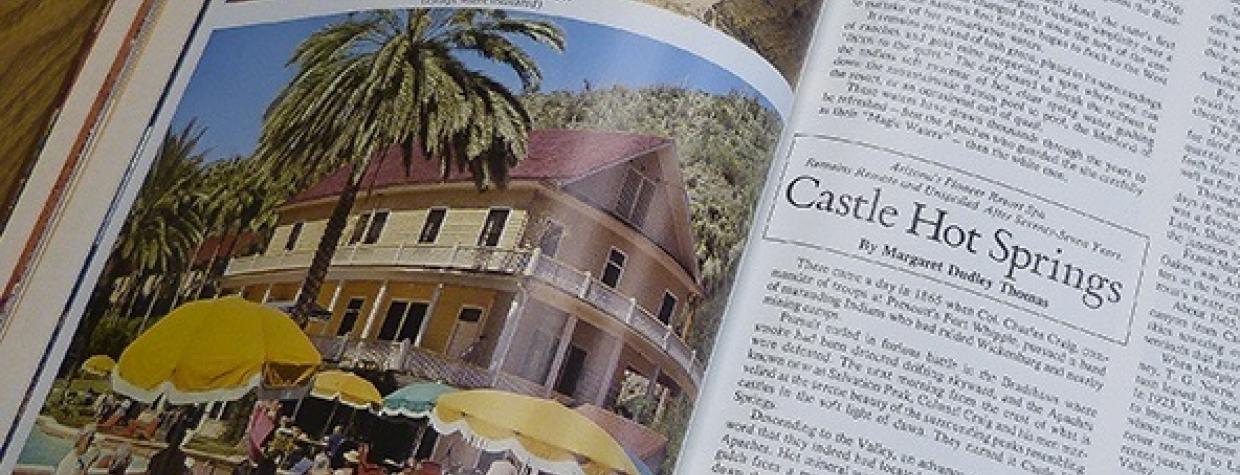

The place boasts the kind of rugged beauty that can’t be found at urban resorts. It’s an oasis — a canola-yellow mansion in the mountains, surrounded by natural hot springs, fruit trees and hiking trails. But it sits at the end of a rough, rocky road that Arizona’s official historian calls “not really passable, and not even jackass-able” after heavy rainfall. It endured fires and floods after it opened in 1896; after a 1976 blaze, it closed to the public.

Nonetheless, three local business partners see an opportunity to revive Arizona’s first resort. Mike Watts and brothers Chris and Howard Nute bought the property for $1.95 million through an online auction in February 2014, and the new Castle Hot Springs owners hope their plans for a spa-resort retreat will put it back on the map.

“For 40 years, people have been trying to do this and haven’t been able to,” Howard Nute says. “We would like to be the people that accomplish that.”

***

Before it became a glamorous getaway, Castle Hot Springs drew an unexpected sort of visitor: “tubercular lungers,” as Arizona’s official historian, Marshall Trimble, calls them.

The therapeutic hot-spring water, which still flows and reaches temperatures of about 120 degrees, was advertised to tuberculosis patients across the country. Miners, Trimble says, also bathed and washed their clothes in the spring water after backbreaking labor in local silver and gold mines. Tonto Apaches and Yavapais in the area soaked in the hot springs.

Soon, however, the resort’s demographics shifted. Guests traveled on private Burlington Northern Santa Fe train cars, hopping off at the Morristown station and climbing onto stagecoaches that transported them to the resort. In its heyday, Castle Hot Springs guests enjoyed accommodations that included swimming, golf, hiking, horseback-riding and tennis — and, naturally, Arizona’s beautiful weather.

Today, only a few structures remain. Fires claimed the Palm House and the Wrigley Building (named after another famous family that stayed there). The bright-yellow Kennedy Building still stands.

Trimble, who recently retired from his position as director of Southwest studies at Scottsdale Community College, has visited Castle Hot Springs twice. His first visit was when Arizona State University, to which the property was donated after the 1976 fire, used it for meetings. He visited again when he wrote a piece about the site for Arizona Highways.

“My son came out from New York City a couple of weeks ago and stayed at the Phoenician [resort] for about three or four days, so I went out and just took some time off and hung around,” Trimble says. “And I thought it’s interesting that here we are in the 21st century, and people are coming out and they still congregate at the swimming pool. Some things don’t change. The swimming suits have changed — a lot — and the amenities have changed, such as people bringing you drinks and treats and things like that.”

Trimble adds that the difficulty Castle Hot Springs will face as it enters the modern resort-tourism business lies primarily in how difficult it is to get there. The road isn’t paved, the resort isn’t near a bustling city, and any vehicle without four-wheel-drive may be in for a turbulent ride.

That journey, the new owners say, only adds to the rugged allure of the resort.

***

Watts began researching Castle Hot Springs when ASU sold it in the 1980s. He later became an investor in the property with David Garrett of Garrett Hotel Group, a company that owned Lake Placid Lodge and other high-end getaways.

After the group’s plan to spend about $30 million to restore Castle Hot Springs flopped, Watts began to track the property. He had partnered with Chris and Howard Nute, the owners of Underground Safety Equipment, for a handful of business ventures through the years and asked the brothers if they wanted to collaborate on the Castle Hot Springs investment.

“Mike is the driver; he’s the majority owner. His vision will be the one that either gets carried out or doesn’t. We’re supporting-role guys — and happy to be,” Howard Nute says. “He’s the best partner you could ever have.”

It’s a Friday morning in early October 2014, and Watts’ helicopter sits outside his spotless, aircraft-filled hangar in Phoenix. It’s a sleek, gray machine lined with silvery stripes and furnished with creamy leather seats. Watts learned how to fly it in 1986.

Watts carefully checks the control panel and prepares for takeoff.

The rotor wings cut through the air with increasing speed as nearby treetops ripple from the aircraft’s gusts. Watts gently lifts the craft off the ground, heading for his 120-year-old piece of historic property.

Heading northwest and rising to about 760 feet, Watts makes a graceful curve to avoid the Ben Avery Shooting Facility.

“We’ll fly south of the range in case there’s someone who gets nervous and wants to shoot at us,” he says.

Lake Pleasant, cobalt blue, creeps into view as Watts explains the constant ricochet between shifting ownerships and ideas for “grand plans” that Castle Hot Springs has endured.

“At one time, someone was going to build a cable car [to the site], but you would be pulling yourself on a wire rope,” he says.

He gently steers the aircraft around jagged mountains, revealing the arduous driving path below and a landscape intensely mountainous yet sparse in greenery. Suddenly, there’s the resort, a yolk-yellow mansion with an entryway flanked by neatly lined palm trees and a drained pool.

Gently, Watts lands the helicopter on the white X stamped into the grass that used to be Arizona’s first nine-hole golf course.

Mike and Jean, the caretakers who live on the building’s third floor, greet us on the front lawn. (They asked that their last names not be used in this story.)

Watts sorts through a box of framed photographs, ads and articles about Castle Hot Springs. One bird’s-eye photograph shows the U-shaped Palm House, which burned down in 1976. Other structures at the site endured the same fate — in part thanks to the poorly maintained road leading to the resort.

“When the Wrigley Building burned down, firefighters never showed up,” Mike says. “They just put out the smoke the next day.”

Mike has taken care of the property for 18 years and outlasted five or six owners. He’s seen buyer after buyer invest funds and energy into the purchase, carry out a few patch-ups and ultimately sell the site — yet he seems optimistic that Watts’ plans for a desert spa retreat will finally bring Castle Hot Springs the luxury that faded from its name.

Mike, who’s been in Arizona since he was 10 or 12, applied for the Castle Hot Springs caretaking position while working for a Casa Grande apartment complex.

“I was changing the trash on Christmas Eve and said, ‘I don’t need this anymore,’” he says. The resort’s location wasn’t disclosed in the job description, but 200 applied for the position.

His favorite part of living far from city lights? “No witnesses,” Mike says. Watts laughs. “Nah, the quiet’s nice.”

The second floor of the yellow building — referred to as the Kennedy Building, after future President John F. Kennedy, who recuperated there after World War II — once served as a greeting and check-in area for guests. It’s gutted now, but Watts points out a few historical gems that remain, including a telephone booth that reportedly housed the phone with Arizona’s first telephone number: 1.

Watts continues up a dirt path behind the yellow building and toward the hot springs that once brought fame to the resort. He points out palm trees he’ll eventually have trimmed, water pipes flanking the pathway that will be buried, and a former laundry building — now a toolshed — that Howard Nute imagines as a swanky bar for guests.

We venture up the winding gravel path to glimpse the resort’s first claim to fame — the crystal-clear hot springs.

Watts plans to route the spring water to private quarters nestled throughout the property to give guests a contemporary, accommodating touch.

Watts understands the resort will never reach the same glamour it had in the old days, but he’s ready to put his plans into action with the Nute brothers. The team has been consulting a local hospitality group and an architect to bring their blueprints to life.

“[It’s important to] build it as you go, and don’t put a ton of money in big buildings like there used to be,” Watts says.

The trio is optimistic this will finally be a successful chapter for Castle Hot Springs.

“It’s a jewel,” Howard Nute says. “Our goal is that it becomes this cool dot on the Arizona map that people need to know is there.”

— Emily Lierle