Man first came to Canyon de Chelly and its tributary, Canyon del Muerto, thousands of years ago. Within this sandstone sanctuary, he found shelter, water and fertile soil in which to grow his corn.

At first, life was simple. Man lived in caves or shelters made of stone and brush. Although he grew some corn, he lived off the land, hunting and gathering wild foods. He wove beautiful baskets but had not yet mastered the art of making pottery.

During the centuries that followed, the Anasazi culture, the name given to these ancient ones, grew. They became an agricultural people. They began to build magnificent stone pueblos and create beautiful pottery and adornments embellished with turquoise. They transformed the canyon walls into a literal art gallery with paintings and inscriptions of abstract symbols and life forms.

But by the dawning of the 14th century, the Anasazis were gone, their canyon hushed, their once-great villages crumbling.

Then came a new breed of man, the Navajo, settling along the canyon floor.

For a while, Hopi families, descendants of the Anasazis, farmed within the canyon, producing crops of corn, squash and beans. And once again the canyon walls echoed with the laughter of Indian children at play.

Now the canyon walls were being embellished with new drawings and etchings, this time by Navajo artists illustrating wildlife, ceremonies, hunting scenes and other events of everyday life. They even painted murals of Spanish soldiers entering their sacred land.

To enter Canyon de Chelly today is to enter a timeless land. Here, the Anasazi villages still cling to edges of the sandstone cliffs, the artistic renderings of early man remain on the red canyon walls, and the Navajos continue to raise their livestock and crops.

In the photographs that follow, I have attempted to capture some of the history and beauty of this intriguing place. However, this portfolio represents but a minute segment of the countless visual treasures that lie within Canyon de Chelly.

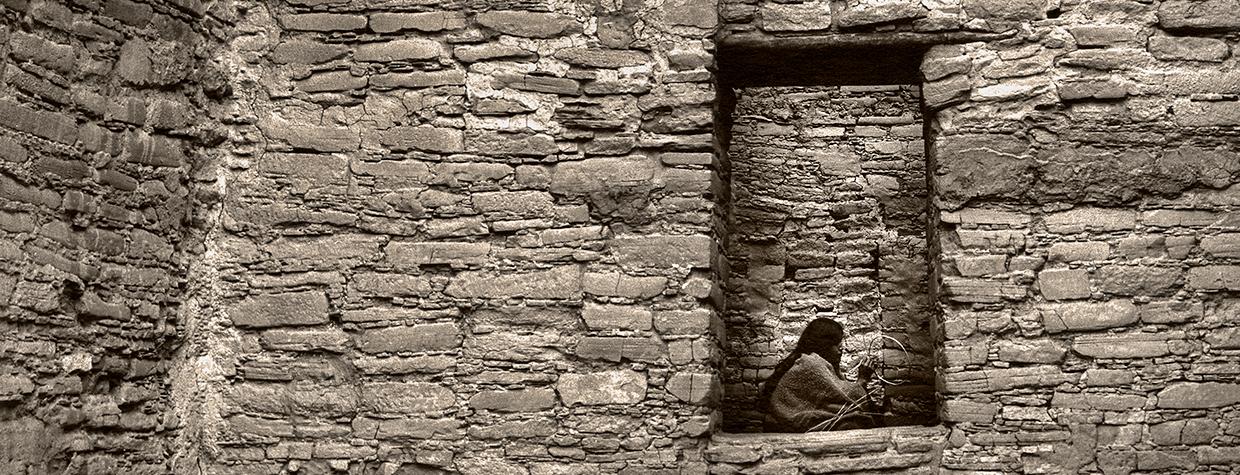

image of the past

Built nearly 1,000 years ago, the walls of White House Ruin frame a portrait of a young woman — a Navajo photographer Jerry Jacka hired as part of a 1981 assignment for Arizona Highways. “What I attempted to do here,” Jacka says, “was, first of all, show the magnificent architecture, but, second of all, to make a person look through this window and say, ‘You know what, people really were living here.’ ”

rock art

Anasazi pictographs, combined with the shapes and textures of the massive cliff walls near Standing Cow Ruin, create interesting art forms. “The thing that drew my attention here was the wonderful art of the canyon itself,” Jacka says. “You could take away all of that rock art, and to me, you would still have a beautiful study of the sandstone walls of Canyon de Chelly. The water and wind erosion on those cliffs is just spectacular.”

Morning at antelope house

Antelope House derives its name from the paintings of four antelopes on a nearby canyon wall. It towers four stories high above the floor of Canyon del Muerto. “I made this just as the morning sun was rising over the canyon,” Jacka says. “There’s a fairly short window of time when light comes in there and strikes what appears to be a tower. Rather than trying to simply show the structure, I wanted to set it in the stage of the textures of Canyon de Chelly.”

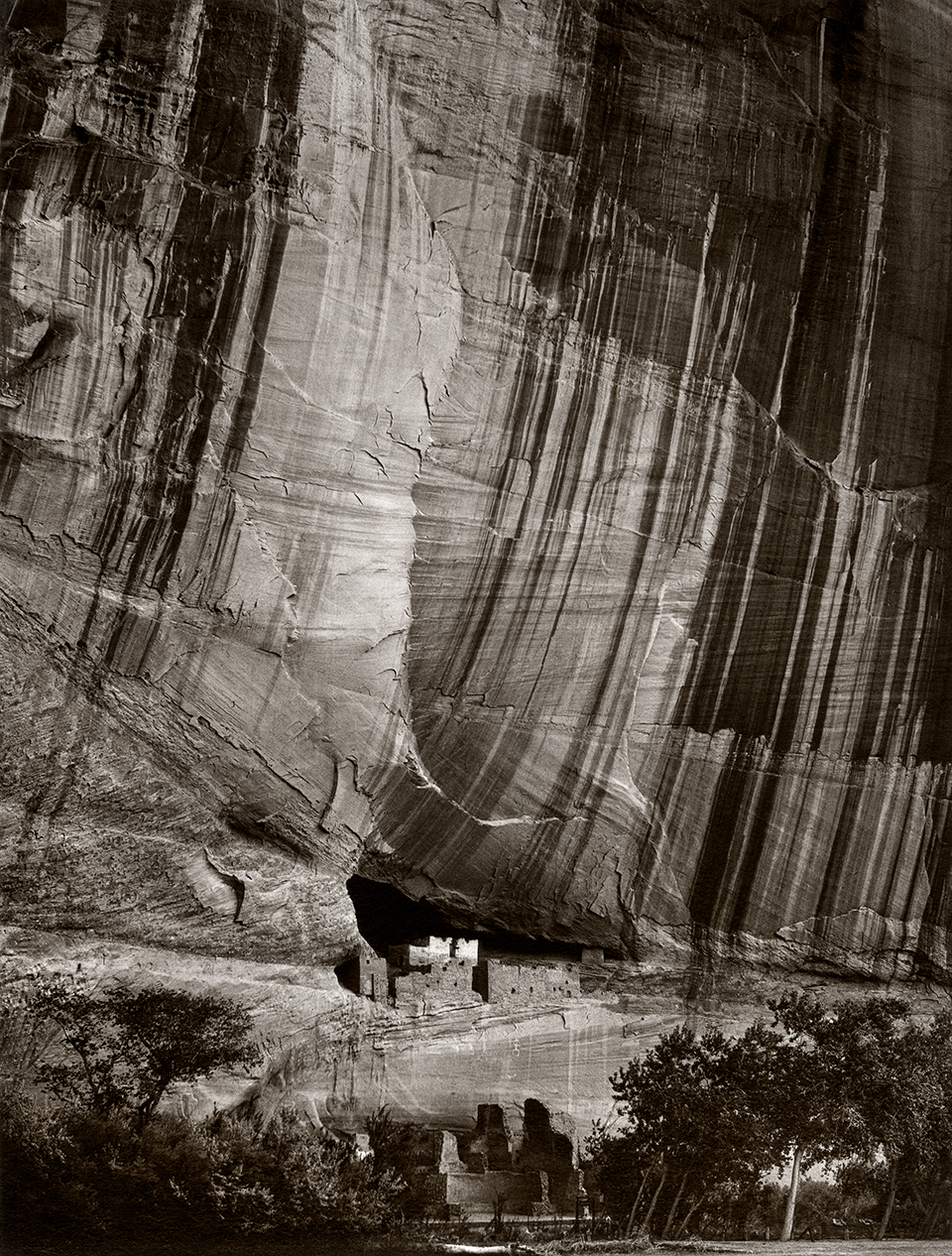

white house ruin

“I don’t think there’s anywhere in the canyon that the mineral staining is more prevalent than it is right there at White House Ruin,” Jacka says. “Again, light. Light is so important. Here, the light is just right. A lot of the lower ruin is in shadow. Then there’s light on the ruin, then on the wonderful stains — like God took a paintbrush and just smeared it there for us photographers.”

walls of white house ruin

Built around A.D. 1050, this honeycomb of ruins was living quarters for the Anasazi people. “This is an afternoon photo, and the light was so important to separate these walls as it did,” Jacka says. “It was just a maze — a maze of walls, of the work of these ancient people, showing the intricacy of the pueblo down below the cliff dwelling. I wandered around and was allowed to step in there, and that was the spot I chose because it revealed the labyrinth of walls and rooms.”

mummy cave ruin

“I had several photos of Mummy Cave, and I kind of busted the mold here,” Jacka says. “Everything I had in the portfolio was vertical. I struggled with this, but I felt like some of my verticals were a little farther back. I wanted people to see the tower on the right. I wanted that one piece of cliff to the left to give it depth and perspective. Every shot has to do with the wonderful walls of Canyon de Chelly — all those textures.”

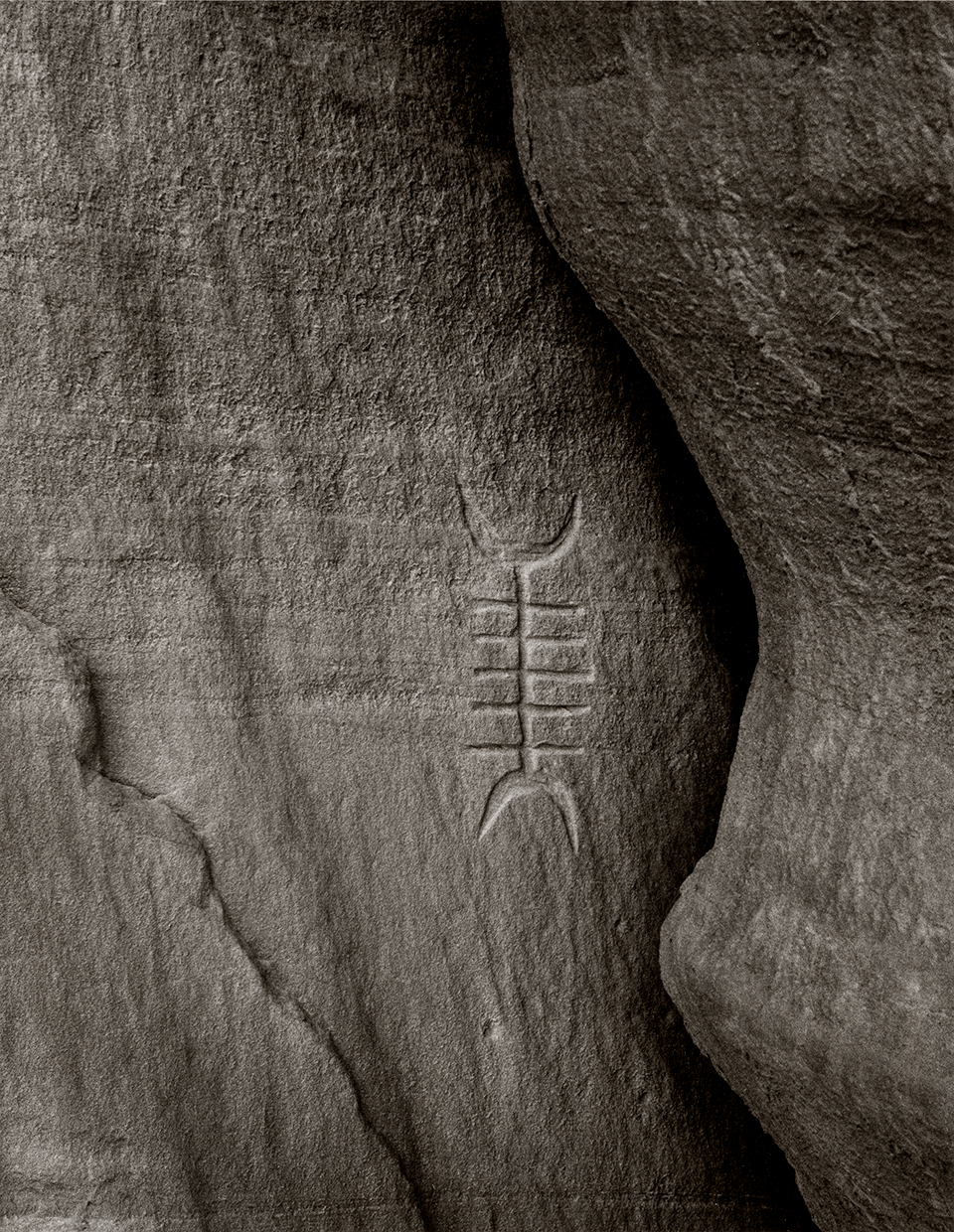

petroglyph

“[This is] so simple,” Jacka says. “And the thing about it is that it’s all reflected light coming in there. That little piece on the right, that sculpted piece of sandstone, just begged to be photographed. I just thought it was so simple and so elegant.”

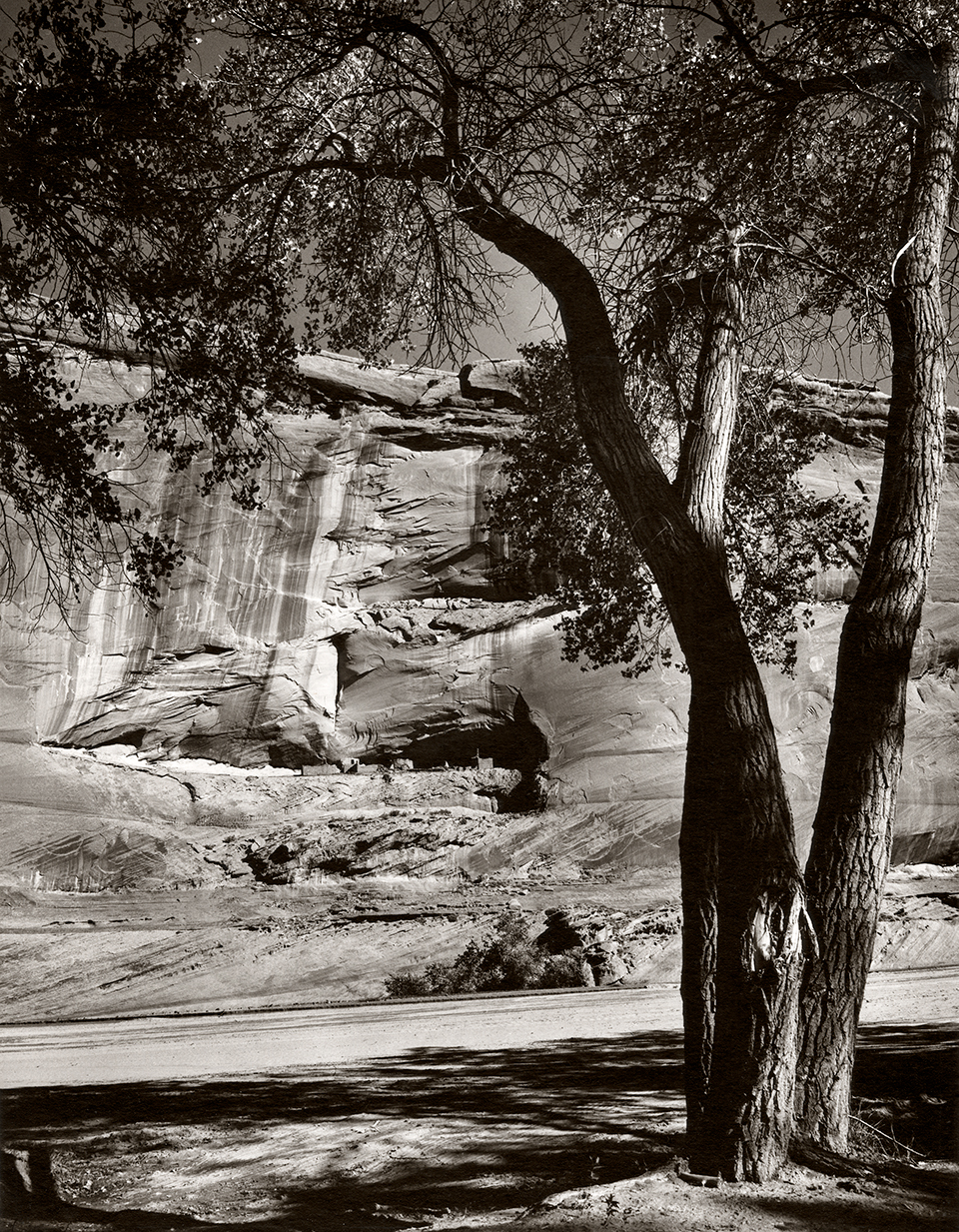

first ruin

“First Ruin is the first cliff dwelling of any significance you encounter at Canyon de Chelly,” Jacka says. “This is midmorning light. The shadow of the cottonwood and an adjoining cottonwood made a natural frame. It worked.” An estimated 800 people lived in the main canyon during its peak period of population.

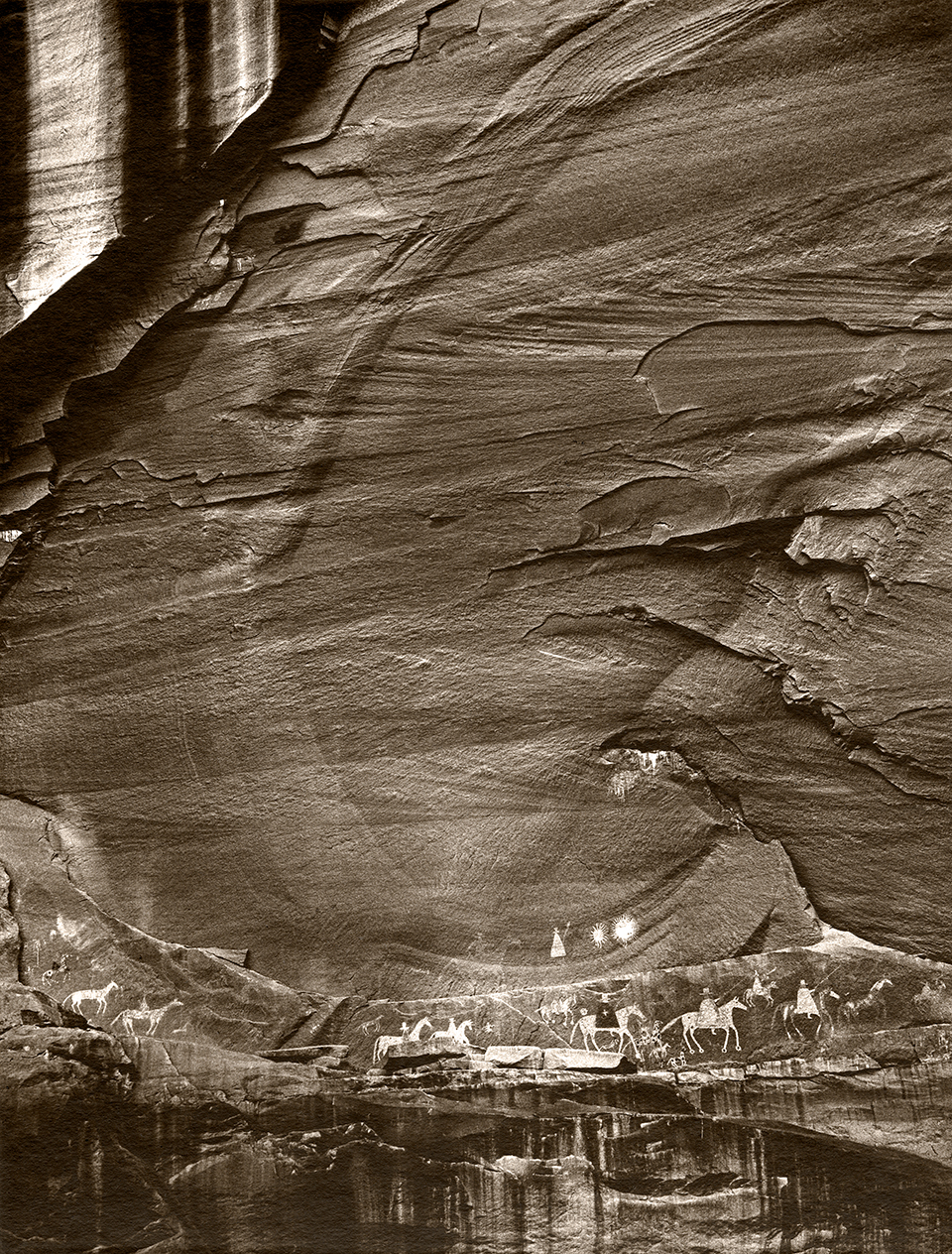

gallery wall

Navajo pictographs in Canyon del Muerto illustrate the arrival of a Spanish cavalry expedition led by Lieutenant Antonio Narbona during the winter of 1804-05. The men killed more than 100 Navajos in Massacre Cave. “This is something that you need to reflect on,” Jacka says. “I chose to not just show the pictograph, but to put it in the perspective of the canyon walls.”

antelope house design

The textures of Antelope House Ruin and the sandstone cliffs contrast with the pictographic art of the Anasazis. “The wonderful thing that happened here is that I was getting light that bounced off the opposite cliff,” Jacka says. “You didn’t really have direct sunlight — although it appears there are rays of light, it’s just highlight from the sandstone.” According to Hopi legends, the swastika represents migrations of ancestors. In one story, Jacka says, “Spider Woman told the people to go out in the four directions, to where the land meets the water.”