Through its open vent, the iron stove flung dancing patterns of light against the far wall of the room. The old Indian watched them through narrowed eyes.

"Grandfather, you should go home now," said one of the younger men in the room, speaking in soft guttural Apache.

"Enjuh," he replied. His friend was right. He would go in a few moments. The whiskey was making his eyelids heavy, ready for sleep.

Yes, he would leave soon. For just a little longer he would watch the dancing firelight. It took him back to the pine-covered ridges of the Chiricahua Mountains far to the west in Arizona. Back to the campfires of long ago.

According to the white man's records, he was beyond 80 years. Perhaps that was so, he told himself. He had, indeed, lived a very long time, and nearly all of the others were gone.

Geronimo was dead; so were Naiche, son of Cochise, and all of the Apache warriors. Gen. George Crook, his commanding officer and good friend, had been dead for nearly 44 years. The other officers with whom he served were gone, too: Captain Crawford, Lieutenants Gatewood and Davis. Most of his scouts were dead, except Toklanni and Martine.

Even President Grover Cleveland was dead. Yes, that giver of medals, the fat liar with whiskers, was dead. "That SOB," the old man mumbled in English.

One of those at the table looked back over his shoulder. "You need a drink, Grandfather?" The old man nodded.

The younger man crossed the room, poured a little, then spoke gently. "It is cold out tonight, Grandfather. The car will be hard to start, and the road down the mountain is slick with the mud from the melting snow. Your wife will worry."

He nodded, then took a sip of the whiskey. The younger man returned to the table. The warmth of the fire wrapped itself around him. The voices at the table drifted away. His eyelids dropped shut, and his dreams carried him back to the Chiricahua Mountains.

The year was 1861. "They accused Cochise of kidnapping a white boy," his mother told him. "A small white boy no older than you. But Cochise does not harm white eyes. He has lived at peace with them."

It was all very confusing. People racing about, tearing down the camp, packing everything so they could slip into the deep canyons where the soldiers could not find them.

"With an Apache, truth is the highest virtue," his mother reminded him. "Cochise told the white soldiers he knew nothing of this boy. They called Cochise a liar and made him a prisoner. But he escaped. Now is a time for war. We will drive all white eyes from the land of the Chiricahuas."

The old man stirred, coughed, and cleared his throat. His mother had been wrong. They could not drive the white eyes away. But the Apache fought with such intensity that, in 1871, the Chiricahua were given back their ancestral land. When Cochise died in 1874, though, the government took the land back, and the Apache were forced to move from their high country to the San Carlos reservation on the desert. Some refused, among them the young boy now grown to manhood.

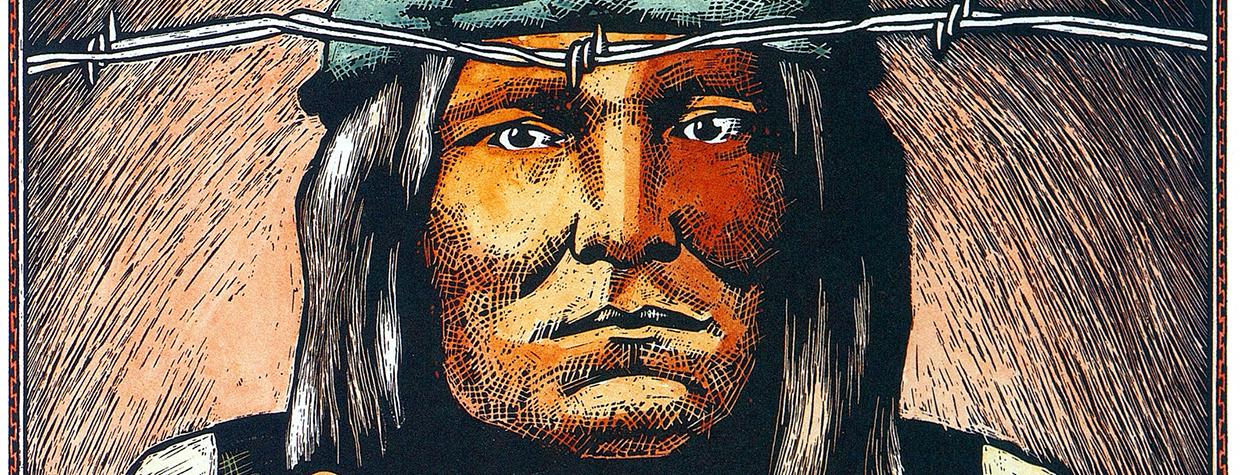

During those growing-up years, living in the camps of Cochise, he had vowed to become a great warrior. And he did. His adult name was Chato, "The Flat Nose." Many members of the U.S. military who fought the renegade Apache during the 1870s and '80s considered Chato, subchief of the Chiricahua, the most brilliant enemy tactician on the frontier, a leader of extraordinary skill and daring. He also was known for his pitiless ferocity and amazing endurance.

While Geronimo remains the most publicized Apache hostile, it was Chato who sent the sharpest tremors of fear across the early frontier. Chato's daring incursion into Arizona in 1883, a lightning strike out of the Sierra Madres of northern Mexico, has earned more space in the history books than any raid of Geronimo's.

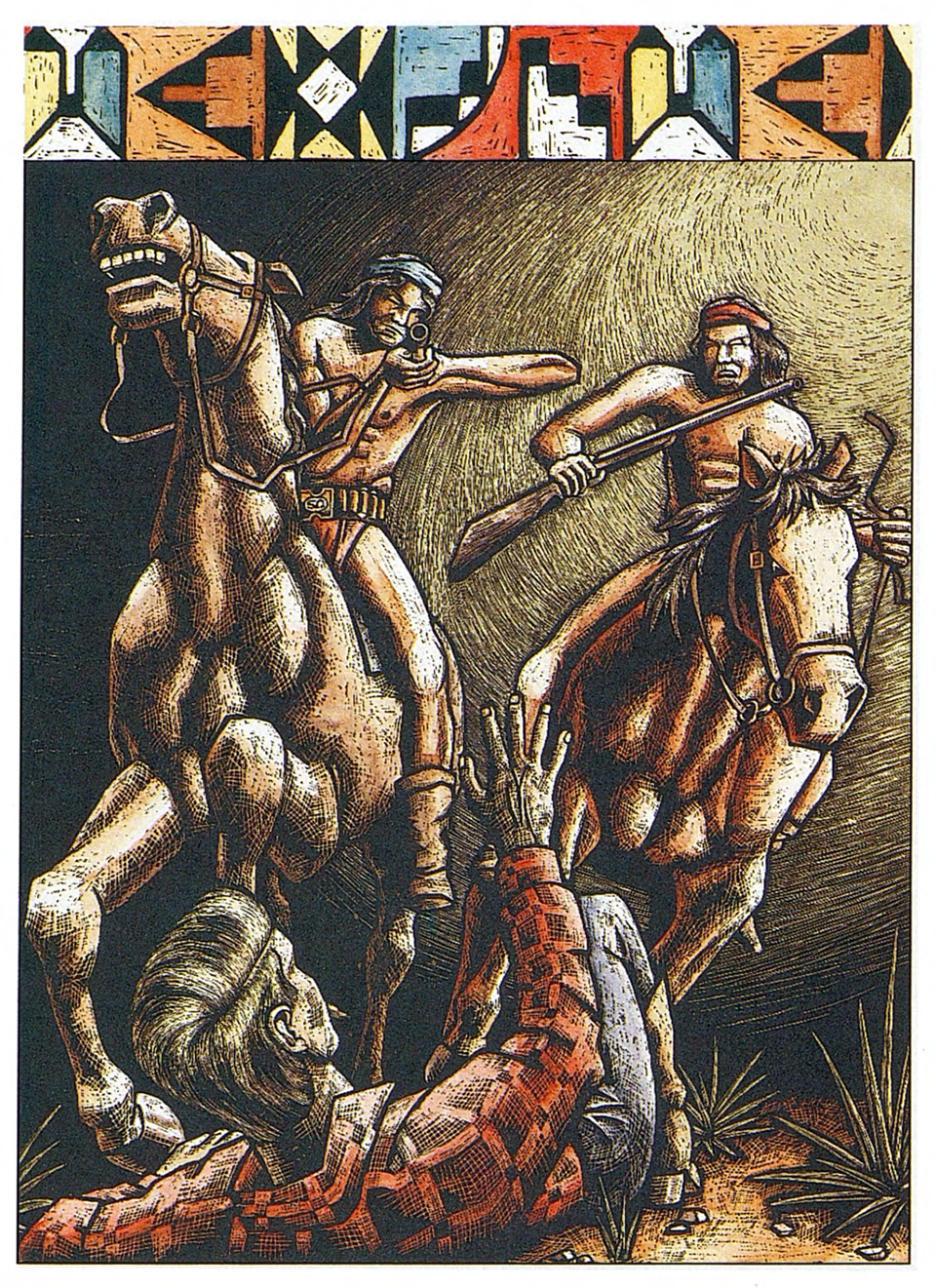

Called an attack of cyclonic swiftness and destructiveness, the raid began when Chato and 26 warriors, armed with repeating rifles, slipped unnoticed across the border from Mexico on March 21, killing settlers and stealing horses.

The assault lasted six days and covered more than 450 miles. Although the hills and canyons were swarming with pursuing troops, not one reported spying a hostile Apache. Years later, Apache warriors who had been on the raid said Chato did not sleep, except on his moving horse. He chose to stand guard each night while his men rested.

One Army officer said of him, "If you think all men are created equal, you have never seen Chato run up one of those hellish mountains in the Sierra Madres."

But in the weeks following his crusade, Chato had other things to concern himself with, besides war. Most prominent: Gen. George Crook was back in the territory.

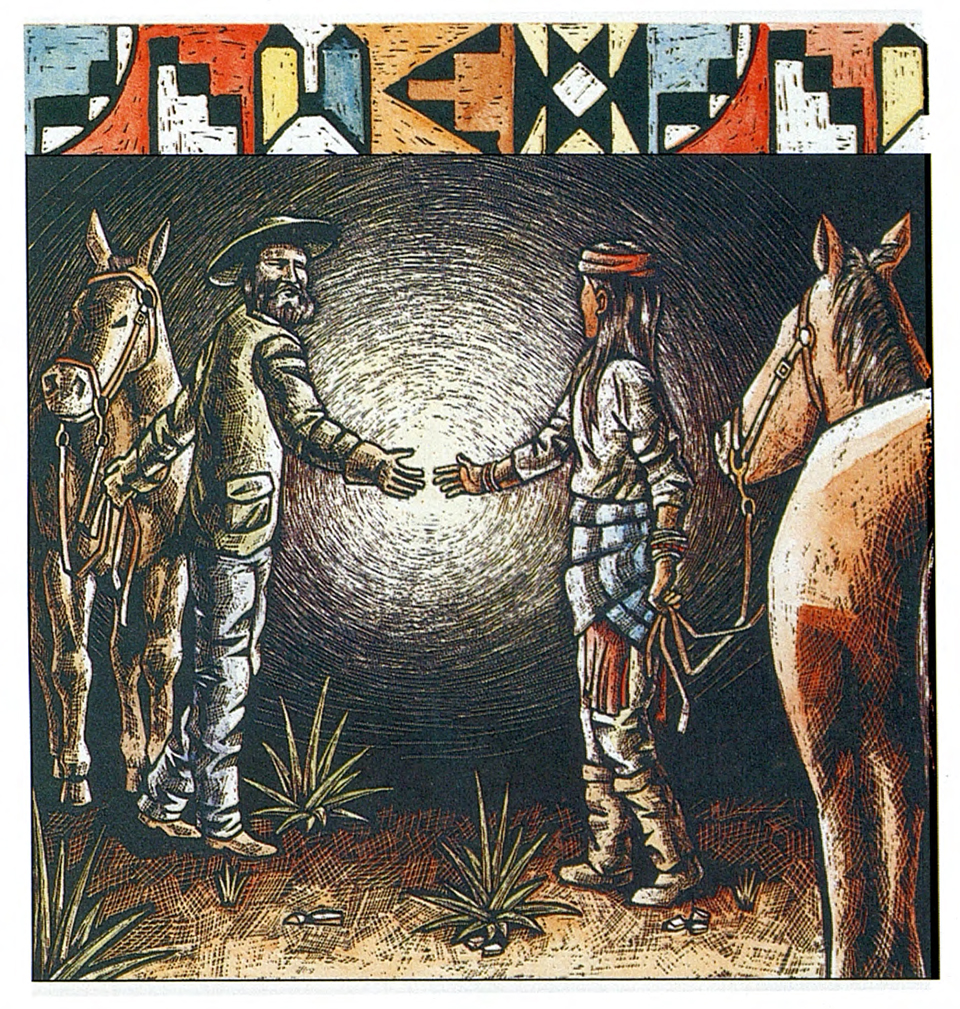

A decade before, in the. early 1870s, Crook had brought peace to the central Arizona frontier. The Apache respected him for his fairness. Nantan Lupan, Gray Wolf, as the Apache called Crook, was a man of honesty and unwavering principles. He told the Indians, "If you live peacefully, I will be your friend. If you choose war, I will kill you to the last man. "

For a time, peace prevailed.

But then Crook left Arizona, transferring to the Department of the Platte in 1875, and troubles began anew.

Then in May of 1883, under an agreement with the Mexican government, Crook rode into Mexico on an expedition against Chato and the other hostiles. That American troops could now pursue them into their last outpost unnerved the Chiricahua and prompted Chato and other renegade leaders to meet with Crook and arrange a return to the reservation. Even Geronimo agreed to surrender, but he failed to show up for nearly a year.

Chato made a pledge to General Crook, the only white man he knew who, he believed, spoke the truth about Cochise. He would remain at peace and be loyal to the U.S. government, serving in any capacity that would benefit the Chiricahua.

By the time Geronimo returned, Chato was setting the example. He had the best farm on the reservation, and he had enlisted in the United States Army. Holding the rank of sergeant, Chato commanded a company of Apache scouts. To Geronimo, it must have seemed the world had turned upside down.

Chato kept a close eye on Geronimo and his cohorts. In May of 1885, Geronimo, after lying to his followers about killing Chato, staged a breakout. But most of the Chiricahua, who actually feared and disliked Geronimo, refused to follow.

General Crook took quick action. His strategy for the subjugation of Geronimo was based on an old and proven belief: only Apache could fight Apache. Crook immediately recruited 200 additional scouts from the camps on the reservation. At the vanguard of his pursuing force, he placed Capt. Emmett Crawford, Sergeant Chato, and Chato's seasoned scouts.

In June, deep in the Sierra Madres, the trail of a renegade band was located. Crawford, sharing Crook's belief that regular Army troops were no match for the Apache, dispatched only Chato and his scouts to engage the hostiles.

The band was located in a canyon that could not be surrounded. Nevertheless, the scouts killed one warrior and wounded several others. A number of horses and 15 women and children were captured.

While not a decisive battle, the incident sent a message to Geronimo and his dwindling forces: Chato was on their trail.

Pursuit of the hostiles continued through the months ahead. The wily Geronimo knew the mountains, and he knew how to run and hide. But each encounter diminished his resources and weakened the spirit of his men. At last, in March of 1886, Geronimo surrendered to General Crook near the Arizona border, but a notorious whiskey peddler named Tribollet sold the hostiles rot-gut and told them the Americans were going to execute them. Geronimo and 37 of his followers bolted from the camp and headed back into Mexico.

Following the escape, General Crook was publicly censured by Philip Sheridan, the commanding general of the Army. For Crook, who had battled bungling bureaucrats and crooked Indian agents for years, this was the final straw. He asked to be relieved of his command.

Gen. Nelson Miles replaced Crook. Miles' strategic emphasis was on the use of white cavalrymen, so Chato, along with a number of other scouts, was discharged honorably from service. He returned to the reservation and resumed farming and raising livestock.

In July of that same year, Chato and a select group of scouts were invited to Washington for a meeting with President Grover Cleveland. As head of the delegation, Chato was led to believe he and his group were to be honored for their services and that discussions would be held regarding the establishment of a more suitable reservation for his people.

In the nation's capital, the Indians were treated royally. Chato was presented with a silver medal, specially cast for the occasion with President Arthur on one side and a small structure called "Peace" on the other. The inscription said: "From Secretary [of the Interior Lucius O.C.) Lamar to Chato. "

At one point, Cleveland suggested that Chato go home and persuade the Chiricahua Apache to relocate to Florida. This was the real reason for bringing him to Washington. But Chato replied that he could not betray his people by sending them to a place he had never seen.

His people, Chato told the President, should be returned to their ancestral lands in the mountains of southern Arizona. Chato, who could not read, asked for a "paper" to that effect. Shortly, he received an impressive- looking document. It was nothing more than a signed certificate verifying that he had been a visitor in the nation 's capital.

Convinced he had succeeded in obtaining a better home for his people, Chato and his scouts left Washington in high spirits. But on the trip home, the train stopped in Kansas. There, armed troops boarded Chato's car and arrested him and his scouts as prisoners of war and held them under guard at Fort Leavenworth.

It was later revealed that the decision to arrest the scouts had been made by a displeased President Cleveland shortly after Chato asked for his "paper." Moreover, it was decided that all of the peaceful reservation Chiricahua were to be arrested, too.

On September 4, 1886, Geronimo, tired of running and hiding, surrendered for the last time and joined the 469 reservation Apache already imprisoned in Florida. Chato and his people were held at the old Spanish fortress of San Marcos; Geronimo and his warriors, at Fort Pickens.

By year end, 18 Apache were dead and many more were ill, the result of poor living conditions and humidity.

After eight months of confinement, the men, women, and children at San Marcos were shunted to Mount Vernon Barracks in Alabama. Geronimo and his people followed in May, 1888.

General Crook was livid over the fate of the peaceful Chiricahua and the betrayal of Chato. In a report to the secretary of war, Crook stated in part:

"The surrender of Geronimo could not have been effected except for the assistance of Chato and his scouts. For their allegiance, they have been rewarded by captivity in a strange land."

A few years later, Capt. John G. Bourke supported Crook's contention in his book, On the Border with Crook, and added:

"The incarceration of Chato and the other faithful Chiricahua can never meet with the approval of honorable soldiers."

Lt. Britton Davis, one of Chato's superior officers and author of the book The Truth About Geronimo, said, "Chato was one of the finest men, red or white, I have ever known. "

"I thought something good would come to me when they gave it [the medal) to me," said the former scout. "Why was I given this to wear in the guardhouse?"

Crook promised his full assistance and returned immediately to Washington to file a report. But less than three months later, Crook died suddenly of natural causes.

Later, proponents of Indian rights, certain military officers, and a few Congressmen worked to help the Chiricahua. Finally, in 1894, after eight years in the deep South, Chato and his people were resettled at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, where they prospered.

In a village complex, overseen by Chato and other influential men, each family was allotted its own land on which to build homes, farm, and herd livestock. Later a sawmill was erected, and children entered nearby schools.

Later still, Chato and a number of the scouts were reinstated in the Army as members of Troop L of the 7th Cavalry and issued rifles and ammunition — paradoxically while still POWs.

In 1913, Chato traveled again to the nation's capital, this time to propose a move to the Mescalero reservation in the high mountains of New Mexico. Following discussions, William Howard Taft, then secretary of war, sent Chato and two other Apache delegates to New Mexico to evaluate the site.

They came back to Fort Sill with a favorable report, and 187 Chiricahua expressed a desire to move west. Geronimo was not among them. He had died in 1909.

Shortly thereafter, the Chiricahua were freed from their status as prisoners of war.

Upon informing Chato that he was, at last, a free man, an officer friend told him, "The United States has fought many wars in many corners of the Earth, but of all the prisoners ever taken, you were held the longest - 27 years. "

For the next two decades, Chato lived a productive life in the forested country of the Mescalero reservation. He was respected throughout New Mexico's Otero County by both Native Americans and the white community.

On that cold evening in March, 1934, Chato had driven to the village of White Tail, at a n elevation of 8,000 feet, to visit friends. At the end of the long evening, when the fire in the iron stove had burned low, when his dreaming was over, he rose from the wooden rocker and slipped into his sheepskin jacket.

"Here is your hat, Grandfather," said the young man, holding out a broad-brimmed Stetson.

The old warrior, still in excellent physical condition, walked out into the cold night and slid behind the wheel of a Model-T. Someone cranked the engine until it chugged to life.

The journey home was downhill through steep canyons. He concentrated at the sharp hairpin turns, guiding the car carefully. The loose rocks and washboard road made the vehicle rattle and shake. On a smooth straight stretch, he relaxed a little. His eyelids fluttered and slowly dropped shut.

He was awakened by the violent motion of the car as it lurched across an embankment and plunged toward the creek below, splashing into the water upside down. The engine coughed, sputtered ... then died. For a few moments, the front wheels turned freely, then stopped.

The headlamps, throwing light on an outcropping above the icy stream, remained on for a long time. Then, slowly, they began to dim. Hours before the first light of dawn, they flickered their last, and the canyon was left in darkness.

William Hafford, whose stories in Arizona Highways were immensely popular, died in November 1992. He was the consummate storyteller, who thrived on the back roads of Arizona. We are all richer for knowing him. His unpublished stories will continue to appear in the magazine.

Kevin Kibsey says that illustrating this story enriched his appreciation of the Apache people.