In 1956, Lawrence Clark Powell wrote an essay titled Arizona: The Wrinkled Land. Of all our contributors, he was one of the most esteemed. Among other things, he was John Steinbeck’s bibliographer and the founding dean of UCLA’s School of Library Science. Later, he served as a professor in residence at the University of Arizona.

In 1950, he was living in London and missing Arizona, his adopted home. “Up to January,” he wrote in the essay, “through summer’s golden end and autumn’s rainbow fall, I turned my back on the far-away Southwest, with no attacks of homesickness. Then one zero morning there fell through the mail-slot in the door something which swung my compass back to the Southwest, and caused the most intense longing for that dry and wrinkled land.

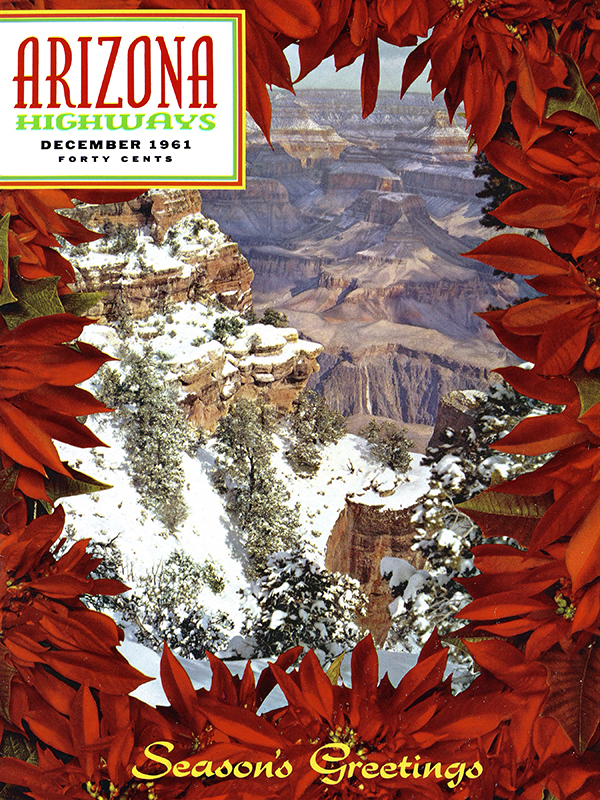

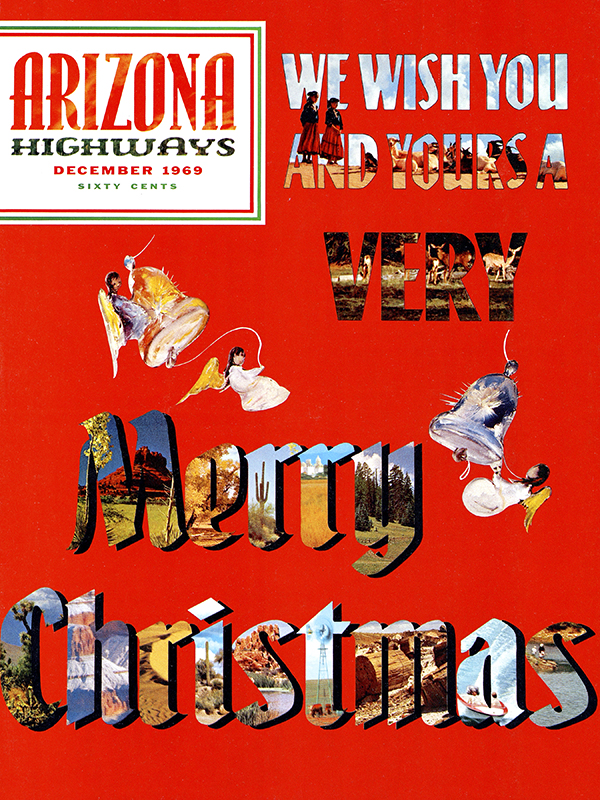

“It was the Christmas number of Arizona Highways, with a splash of spidery poinsettias on the cover. It made me long for home. London in winter had become a foggy desert, while Arizona’s landscape, pictured in the magazine, was paradise, no less. Actually, it was that brilliant number of the country’s most colorful magazine that got me through London’s worst winter since 1066. I used it as supplementary heat; not burning it, no — rather by propping it open on the mantel and letting its pictures irradiate the room.”

His reference to our magazine as “the Christmas number” wasn’t unusual. In 1950, Arizona Highways was overtly non-secular. And Raymond Carlson’s editor’s letters often read like Scripture. One December, he recounted the birth of Jesus. Another year, he led with a biblical prayer: “May we rejoice together, O Lord, during this the Holy Season in observance of the sacred anniversary of Thy birth.”

After Mr. Carlson’s retirement in 1971, Joe Stacey, his successor, kept it non-secular. The tone, however, began to change with our next editor, Tom Cooper, who still referred to Christmas, but with less emphasis. It was a change that disturbed Cathy Schaller of San Gabriel, California.

“How can you call this a Christmas issue,” she wrote in a letter to the editor, “when the only things that differentiate it from any other month are the wreath on the front and the words ‘Season’s Greetings’? The pictures in the latest issue have never been more beautiful. But without the underlying theme, which used to be present, it lacks substance and seems to us quite pagan.”

No doubt, Mr. Cooper heard from several other disillusioned readers, which is what led to his response a couple of issues later. “We are a tourist orientated magazine,” he wrote in February 1977, “published for the sole purpose of encouraging tourism into and through Arizona. We are not a religious publication. In fact, whenever references to God or Jesus Christ appear on our pages, we hear from those who believe that the mention of a God violates the mandate of separation of church and state. The U.S. Postal Service encounters this same problem: Some want religious scenes on Christmas stamps; others clearly object to a governmental agency dabbling in scenes associated with God or religion. You can’t please everyone.”

The establishment clause of the First Amendment has been debated for decades, but even under the most stringent interpretation, it’s a stretch to say that wishing readers a “Merry Christmas” is a violation of the separation of church and state. James Madison was worried about more threatening scenarios. Nevertheless, Mr. Cooper was right. You can’t please everyone.

That tenet remains true so many decades later. However, even in a world as polarized as ours, we can all relate to Bob Cratchit’s high spirits on that wintryChristmas Eve when he left behind his servant’s desk and headed home to Camden Town in the foggy darkness. His pockets may have been empty, but his heart was filled with the joyful anticipation of his daughter coming home, eating Christmas pudding and shoveling chestnuts onto the fire. Lightheartedness. Love. Good cheer. Christmas. Or the spirit of Christmas. That’s been at the heart of our December issues from the beginning.

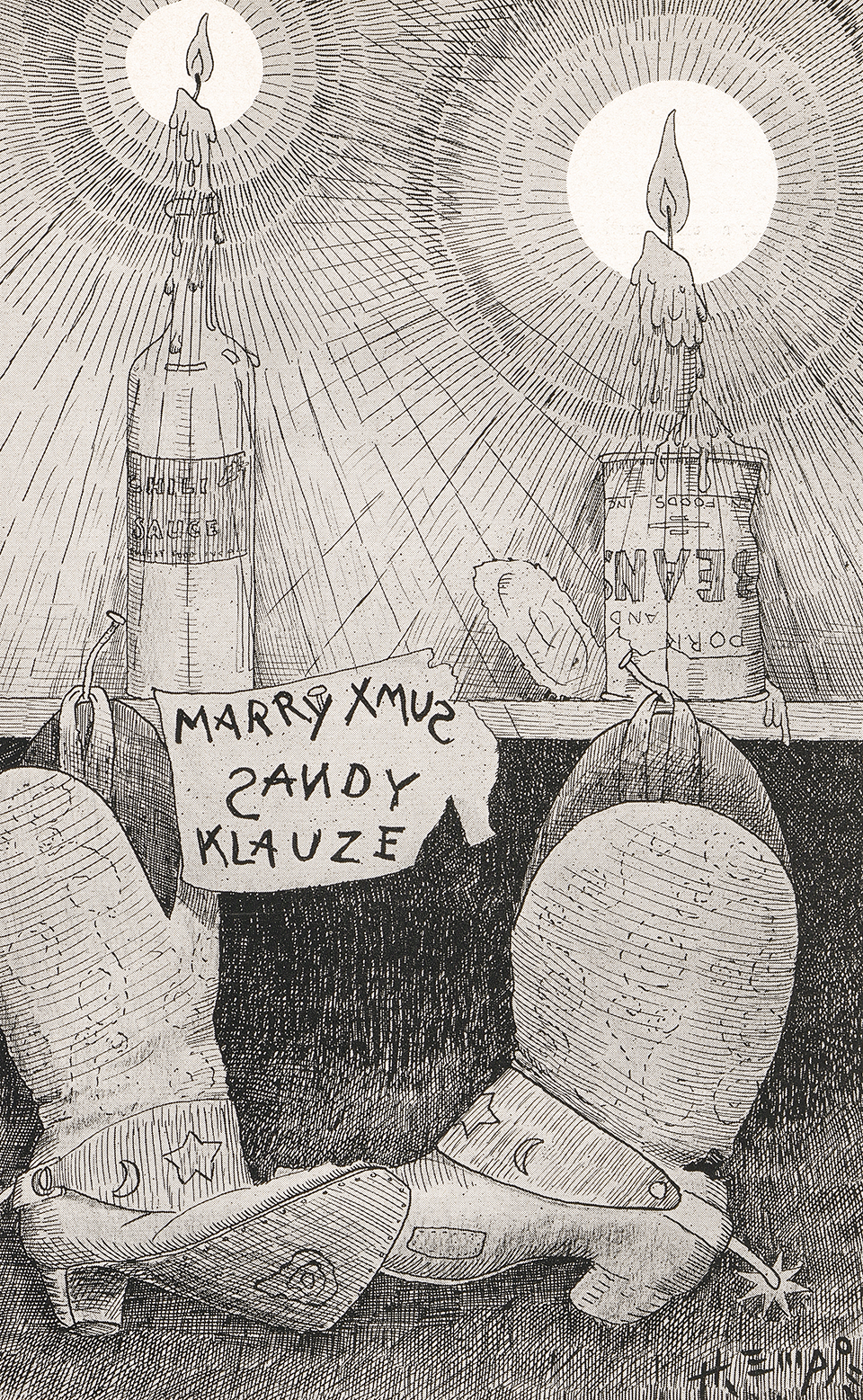

“Marry Xmus Sandy Klauze.” That was the caption for the “Christmas card” on page 1 of our December 1938 issue, Raymond Carlson’s first Christmas edition. The cartoon, which had a Western theme, was created by Hal Empie — Mr. Carlson referred to him as “that strange genius down Duncan way.”

In his column that month, our editor signed off without quoting Scripture from Matthew or Luke. The salutation was subdued compared to the sermons he’d write later on. “We hope you find our modest issue to your liking,” he wrote. “Until we gallop along next time, we extend to our friends and readers all the happiness, all the kindness, all the joy the ages-old expression implies: ‘MERRY CHRISTMAS!’ ”

After that, there was no holding back. In October 1939, Mr. Carlson teased the upcoming Christmas issue. “While we do not know how it will all turn out,” he wrote, “we are preparing an extra-pretty magazine for December! This will be brimming with the Christmas motif and should be interesting to everyone. As a suggestion, you might send it to friends out-of-state, for we believe it will be as nice as a Christmas card. Last Christmas we were flooded with subscriptions that people sent out for Christmas presents. Without sounding too commercial, may we suggest that a year’s subscription to Arizona Highways is a fine Christmas gift. And the tariff is only One Dollar. A swell chance for you to be Santa Claus!”

When that issue rolled off the presses two months later, it was, indeed, brimming with a Christmas motif. Mr. Carlson put a cross on the cover — it’s a beautiful photograph of Mission San Xavier del Bac by Esther Henderson — and inside, there were seven stories dedicated to the holiday. The next year, Mr. Carlson shared his intent to make our December issues something special. “These are the days of the Yuletide,” he wrote, “when the Christmas bells ring out. In deference to the season, and as special greetings to all the world from Arizona, Arizona Highways fits itself in more colorful dress than usual and joins the gaiety of Yule.”

Readers noticed our fancy new clothes.

“The December issue of Arizona Highways,” Ernest McGaffey of Los Angeles wrote, “with Miss Esther Henderson’s magnificent color cover, leaves Roget’s Thesaurus, Crabb’s English Synonyms and Webster’s Dictionary helplessly lost for adjectives to match its pictorial marvels. Your numbers for 1940 have all had some remarkably fine displays, but this Christmas issue leaves every other American magazine behind, further than you can shoot a cannon.”

Our colleagues noticed, too: “I just want to add my congratulations to the hundreds of others I know you will receive for your beautiful Christmas number. I think you have set a new high, not only for the Southwest, but for the entire United States. It is a beautiful book, reflecting credit to you and your staff and the printers.”

The letter was sent by Randall Henderson, editor of The Desert Magazine, a friendly competitor based, at the time, in El Centro, California.

From that point forward, our December issues would be an annual exclamation point. The denouement of another year. However, in 1941, the mood was more subdued. Our editor was anxious, like so many others, about what was happening overseas.

“Christmas 1941 is a memorable Christmas for us all,” he wrote. “The bells of Yule ring out, the light streams from unshuttered windows, carols are sung in the streets. Far, far different is Christmas in other lands where the many little people shudder before the terrible grimaces of the gods of war. Unhappy people! Unhappy world!

“Christmas should be something more for us this year than a few cards exchanged in the mail, a few gifts, a few greetings. We should join together in one great, strong America dedicated to the belief that the Message that has come down the ages rings as true today as it did one day in the little town of Bethlehem.

“This is the hope and faith that has made America strong and unafraid. It stands for goodness and decency, for family ties and affection, for brotherly love. It’s the religion of democracy, the ties that have brought together on our good, rich soil peoples from all the lands on earth, speaking every language, believing in every creed, becoming Americans all.

“We must believe in the spirit of Christmas if we are to understand our past and if we are to have faith in our future. American pride and American courage, the honesty and the goodness that is in the American people, the beauty and the strength and the freedom that is America — all these things must resound as the trumpet call of hope and faith to the suffering peoples of the world in the simple American phrase this Christmas of 1941: Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year to you all.”

“This is the festive season, the season of family and friends, the season of home and fireside,” Mr. Carlson wrote in December 1946 after returning from the Pacific, where he served in World War II. “This is the season when, if we are wanderers in the world, we think of familiar faces and familiar places, and our thoughts travel the intervening miles. The wounds and sorrows of War are fresh and vivid, but as the Yuletide approaches and the New Year comes, we enter the season cheered with the hope that our world will be a better and happier place for all. May this Christmas bring you happiness and good cheer, a crackling fire in the hearth, your friends and dear ones with you! May the New Year bring you the good things of life, days of peace, serenity and contentment! This is our wish for you, whoever you are, wherever you may be!”

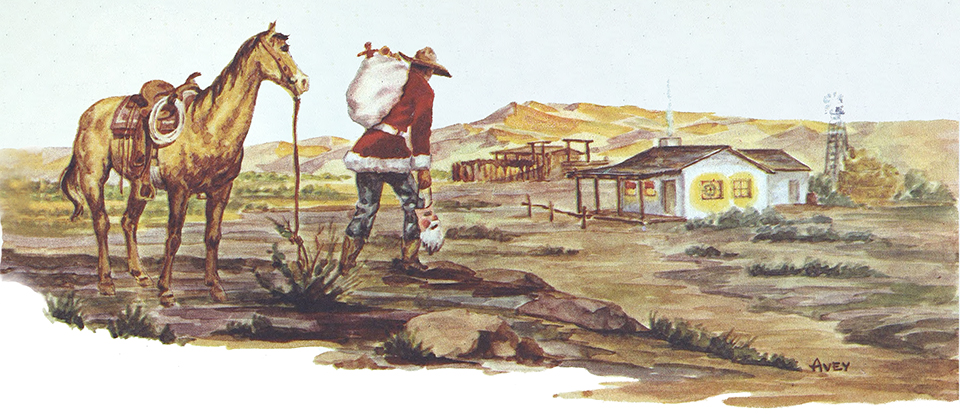

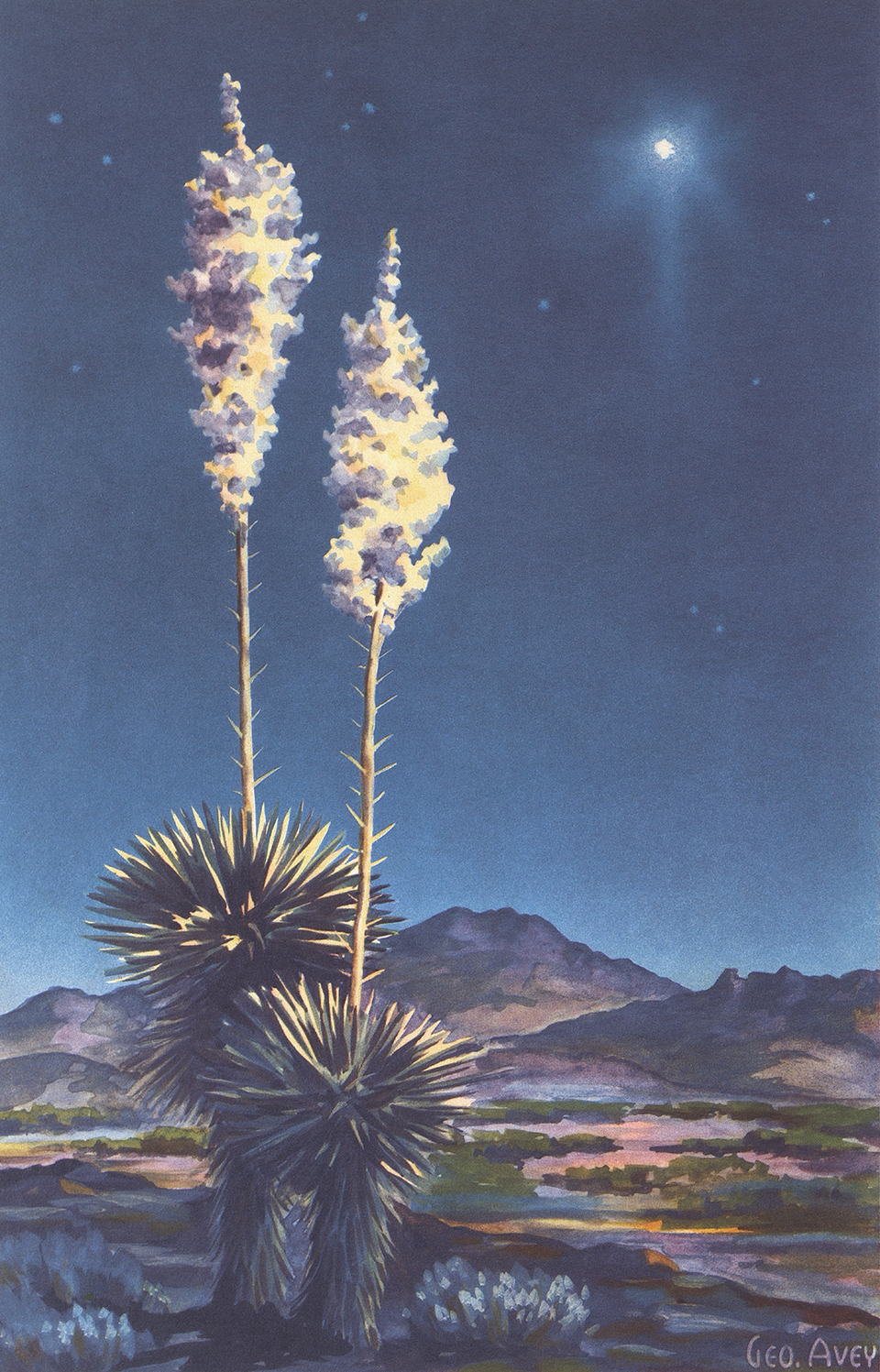

After the war, George Avey, who had been working in tandem with Mr. Carlson since the late 1930s, was officially added to the masthead as art director. His beautiful artwork became a recurring splash of color that complemented so many stories. In December 1947, we published an illustration of his that featured a cowboy dressed as Santa Claus — he’s delivering gifts to a small ranch house, smoke rising from the chimney, in what looks to be Southern Arizona. The next year, on the inside front cover, we ran one of Mr. Avey’s watercolors. It’s another Southern Arizona scene, with yuccas, mountains and a starry night. The caption reads: “Silent Night, Holy Night.”

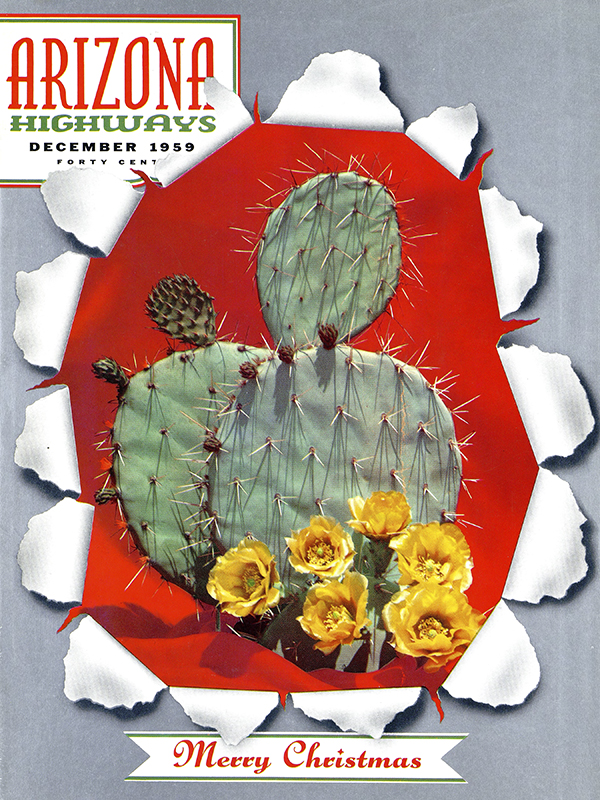

Mr. Avey’s impact on the magazine cannot be overstated, and in 1949, he began using his talents to transition our December covers from “pretty pictures” of random scenes to artistic interpretations of Christmas. “December’s front cover is a study by Claire Meyer Proctor,” the 1949 caption read. “The plant shown is Pyracantha yunanensis, commonly called ‘Fire Thorn.’ Pyracantha, a native of Korea, is widely used as a decorative plant in Southern Arizona. It thrives in hot weather. The red berries appear in late fall and are profuse during the Christmas season.”

The cover looks like a Christmas card, and that was intentional. Jim Stevens, our visionary business director, understood that our December issues could be used to boost subscriptions around the world. “Americans were on the move,” Don Dedera, our 10th editor, wrote about the post-Depression era. “And to keep in touch with one another, they turned to the greeting card. And those who touched or traversed Arizona in those days chose Arizona Highways as their premier holiday card. They might send five-cent cards to their friends, but to Mother, they mailed a 10-cent copy of Arizona Highways.”

In December 1949, we printed 300,000 copies. The next year, that number rose to 350,000. Eventually, our December issues would surpass a million copies and come to be known as a “Christmas Card to the World.”

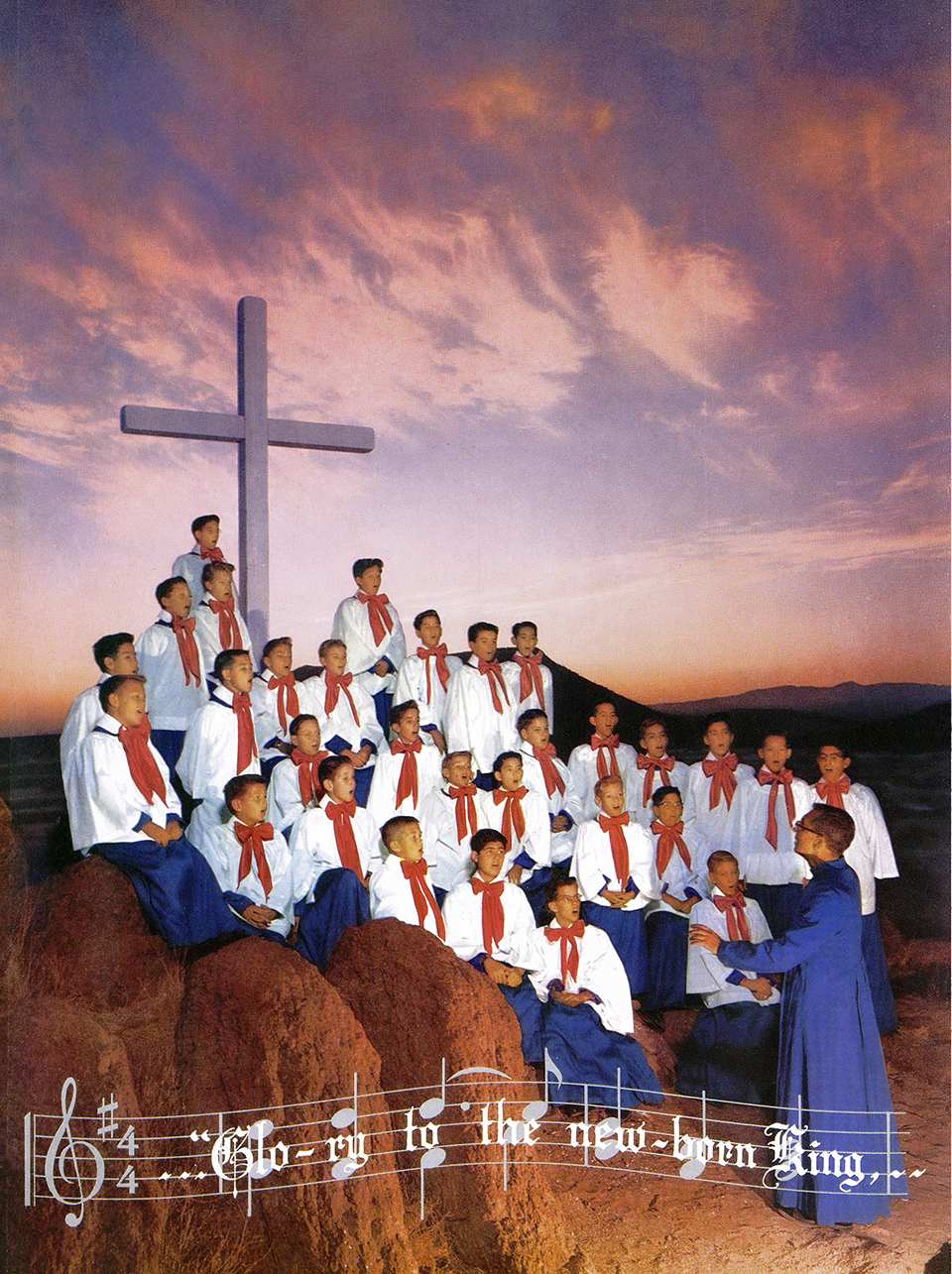

Meantime, our editor continued with his warm Dickensian greetings. “Always there is Christmas,” he wrote in 1951. “There will always be Christmas as long as there are on earth unselfish men and women who can think of others as well as themselves. Christmas is a package done up in tinsel and wrapped with a pretty ribbon, gay gifts of remembrance. It is a tree with bright lights, smelling freshly of the forest. It is a candle in the window whose cheery light speaks a friendly greeting to the world that passes by.

“Christmas is the sparkling diamonds of light in the eyes of a little child opening the gifts of the Season, the delighted cries of children playing with their toys and the pleasure in the eyes of parents seeing their children so happy. It is the warm handclasp of friends expressing in a word or so the joy and the generous spirit of true friendship. Christmas is the beloved carols of Yule sung by your neighbors on your doorstep, and the sermon preached in the little church up the street, and the hymns sung by the choir proclaiming ‘peace on earth; good will towards men.’ Christmas is your mother in the savory kitchen, preparing the turkey for dinner, and your dad busily getting in the way.”

Eddie Augustiny was talented, and some critics even called him a “top notch” artist, but he never became famous. Not like his wife, Joyce Ballantyne. She was one of the most successful pinup artists in the golden age of ad design. Her best-known image, which she created for Coppertone in 1959, featured a young girl in pigtails whose bathing suit was being tugged at by a small dog. You’ve seen it.

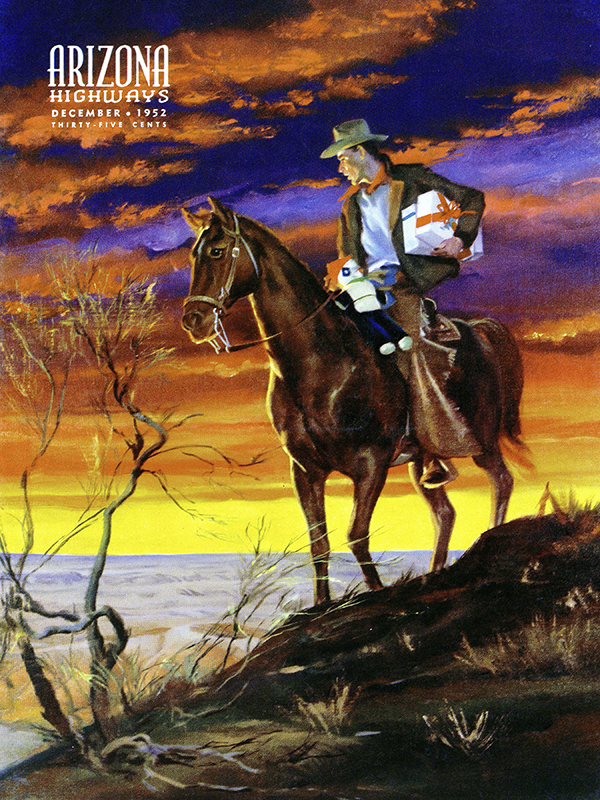

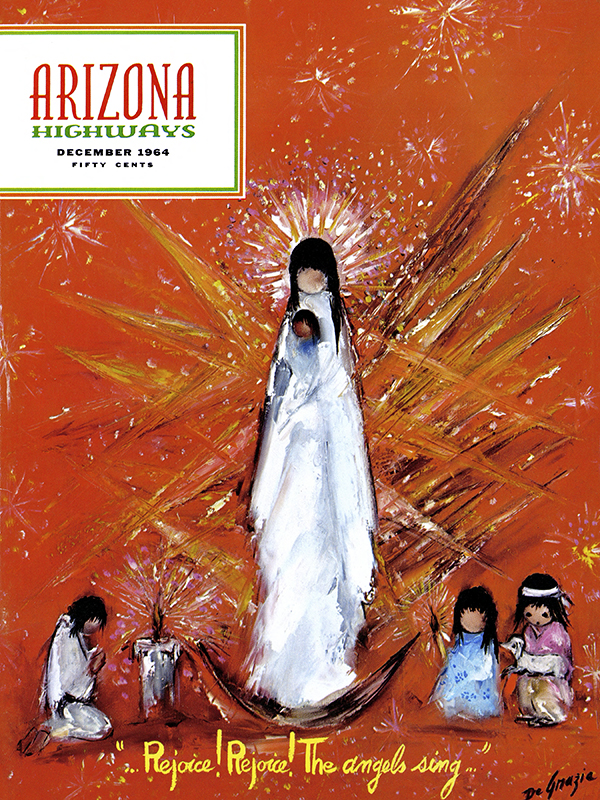

The two artists met at the American Academy of Art in Chicago, got married, moved into an apartment on the Near North Side, set up side-by-side easels and had a daughter named Coby. By 1949, Ms. Ballantyne’s list of clients included Coca-Cola, Kraft, Ovaltine, the Chicago Tribune and Sports Afield magazine. Her husband worked for us. Once. In December 1952. And there wasn’t any fanfare. Just a 10-word cover credit: “Christmas Eve in the Far West. Painting by Eddie Augustiny.” Yet that cover, which features a cowboy on a horse, with Christmas presents in his arms, is one of our most beloved. And it kicked off a string of 18 consecutive December covers that rank as the very best of our “Christmas Cards to the World.” Like Macy’s Holiday Windows, they were vibrant reminders that it was Christmastime — the most wonderful time of the year.

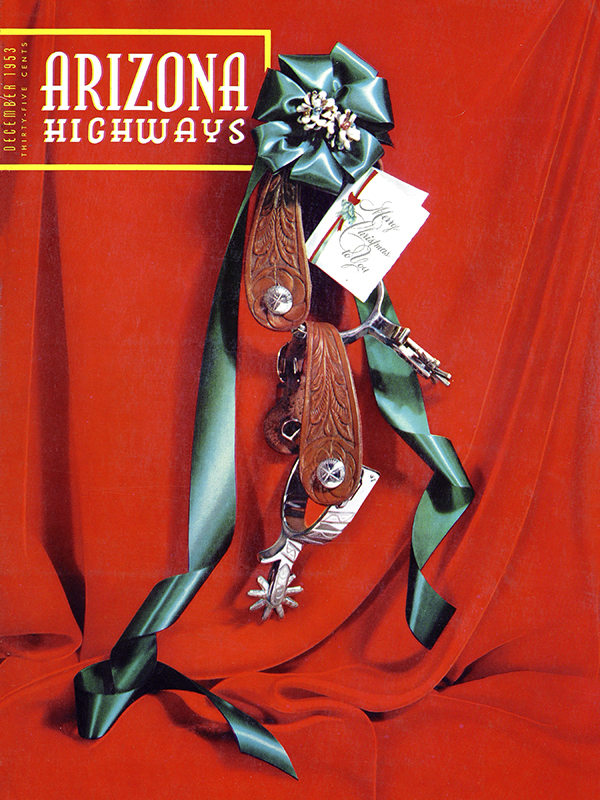

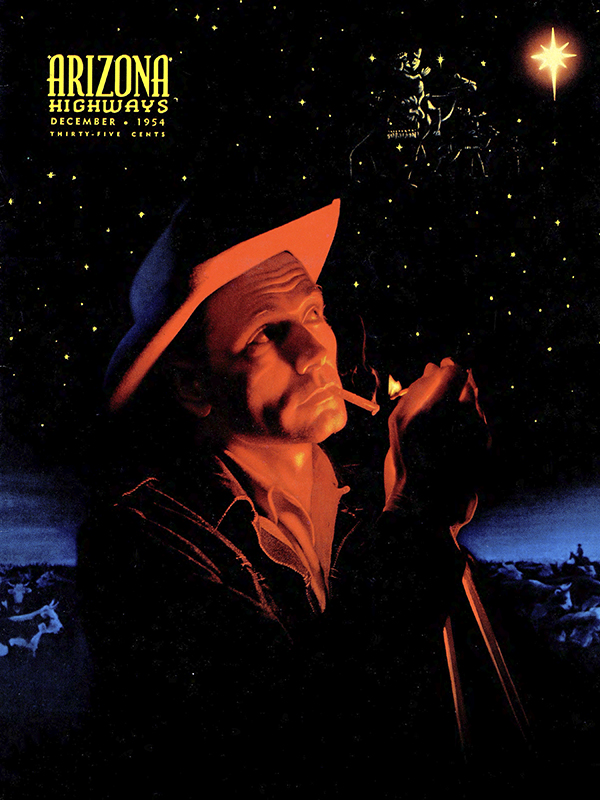

Allen C. Reed got the next two December covers. In 1953, we ran his photograph titled A Christmas Card — Western Style, which features a cowboy spur wrapped in a green bow with a gift tag. The next year, he created a photo illustration titled Silent Night — Holy Night. It’s a staff favorite, but we’d never run that image today. The mirage of Santa’s sleigh in the sky and the North Star are nice, but the cowboy lighting a cigarette wouldn’t make the cut. Nevertheless, our readers loved it.

“I have to hand it to your Allen Reed for coming up with a dramatic cover for your Christmas magazine,” Laura Anthony Smith of Los Angeles wrote. “I have never seen photography and art used together so artistically.”

Hamilton Hampton, a subscriber from Detroit, liked it, too.

“Did you know that the cover on your Christmas issue glows?” he wrote. “We received our first copy about the 5th of last November as the beginning of a Christmas gift subscription from a friend. We were charmed with the magazine and are looking forward to the copies to come. We placed the copy under our Christmas tree. One night, when we had turned out the lights and there was only the illumination from the candles of our Christmas tree in the living room, our small son came in. He shouted: ‘Hey, the magazine’s on fire!’ He was almost right. In the sparse light, the cowboy’s face on the cover stood out bright as in firelight. The effect was eerie.”

In response, our editor wrote: “About the middle of December, our worries were over. Our Christmas issue was in as far as subscriptions and newsstand sales were concerned. The response was most encouraging, and for that we are grateful.”

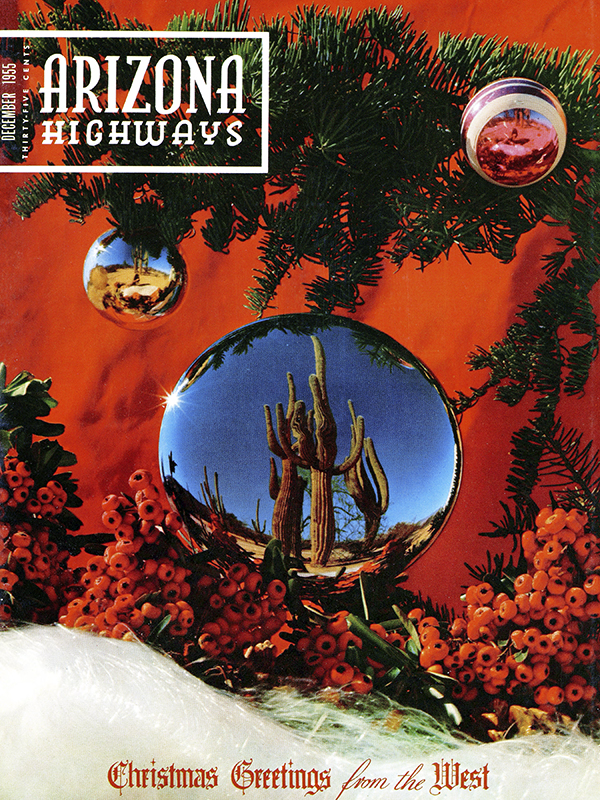

Josef Muench got the December cover in 1955 with a photograph titled A Desert Christmas Card. The bar was getting higher, and Mr. Muench hit the mark. Once again, readers were impressed.

“I use several hundred of your December issues for my Christmas cards each year,” S.K. Howart of St. Louis wrote, “and you have never let me down. I think your last was one of the best yet. Congratulations! Incidentally, last week I attended a meeting of photographers here, and there was much discussion about your cover. How did Josef Muench go about creating such a masterpiece?”

“We are glad Mr. Howart and so many of our other readers liked our December issue,” Mr. Carlson wrote. “And we are glad to tell you about Joe’s striking cover picture. The scene is an actual photograph with no tricky double exposures or overprints. Joe and Joyce (Mrs. Joe) set up the Christmas props and decorations in Saguaro National Monument near Tucson. The reflection of the saguaros in the baubles was carefully achieved by placement and careful use of natural light. When they had the effect they wanted, the photograph was taken, and we think it turned out real nice.”

And so it did.

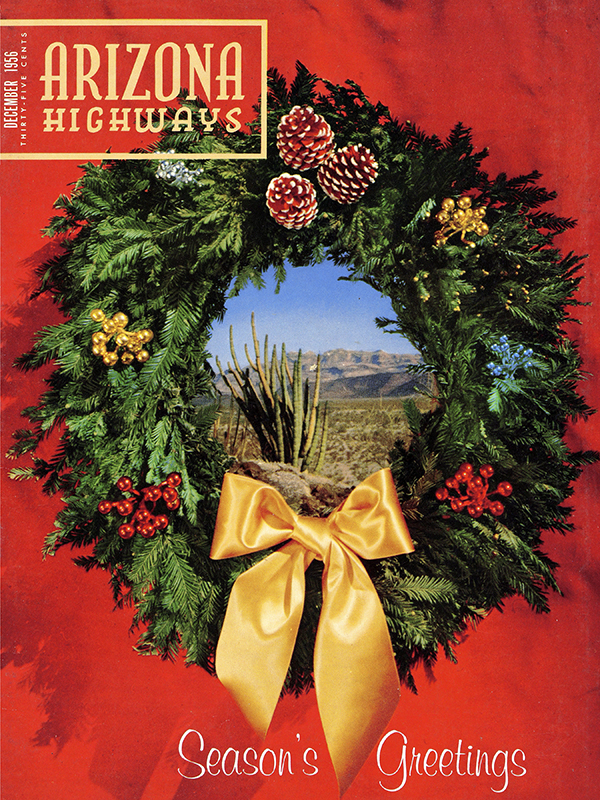

The next year, we hit a coveted milestone: In December 1956, we printed a million copies of our Christmas issue. It was produced “in its entirety in ‘Micro-Color’ lithography by the W.A. Krueger company, 3830 West Wisconsin Avenue, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.” And our cover stock was Warren’s Offset Enamel, which had a 150-pound base.

That month, Mr. Carlson’s column was titled O Joyous Day … O Joyous Day. It refers to the birth of Jesus, but selling a million copies of the magazine would have given our founding fathers another reason to celebrate. The milestone called for a party. And, like Old Fezziwig, they knew how to throw a party.

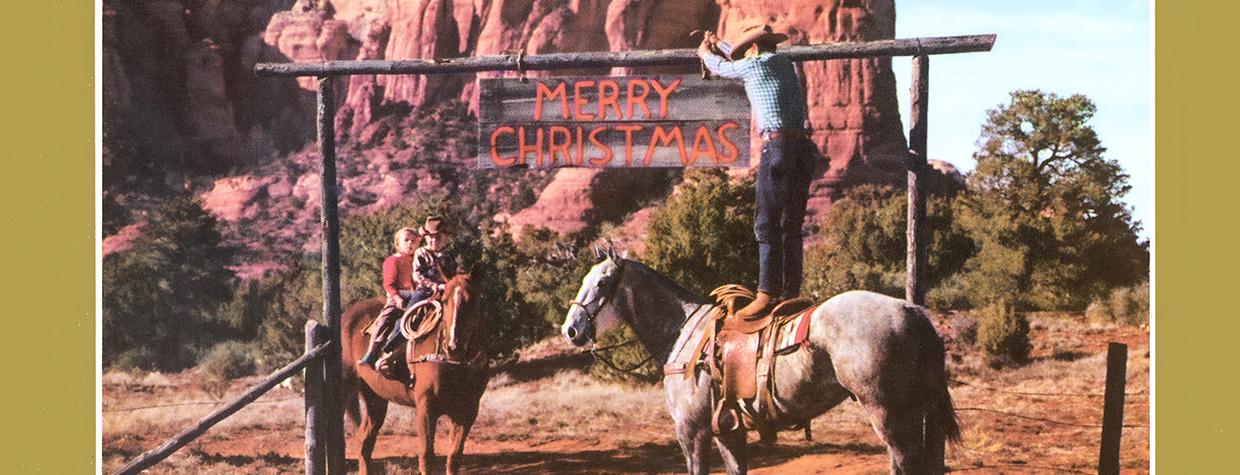

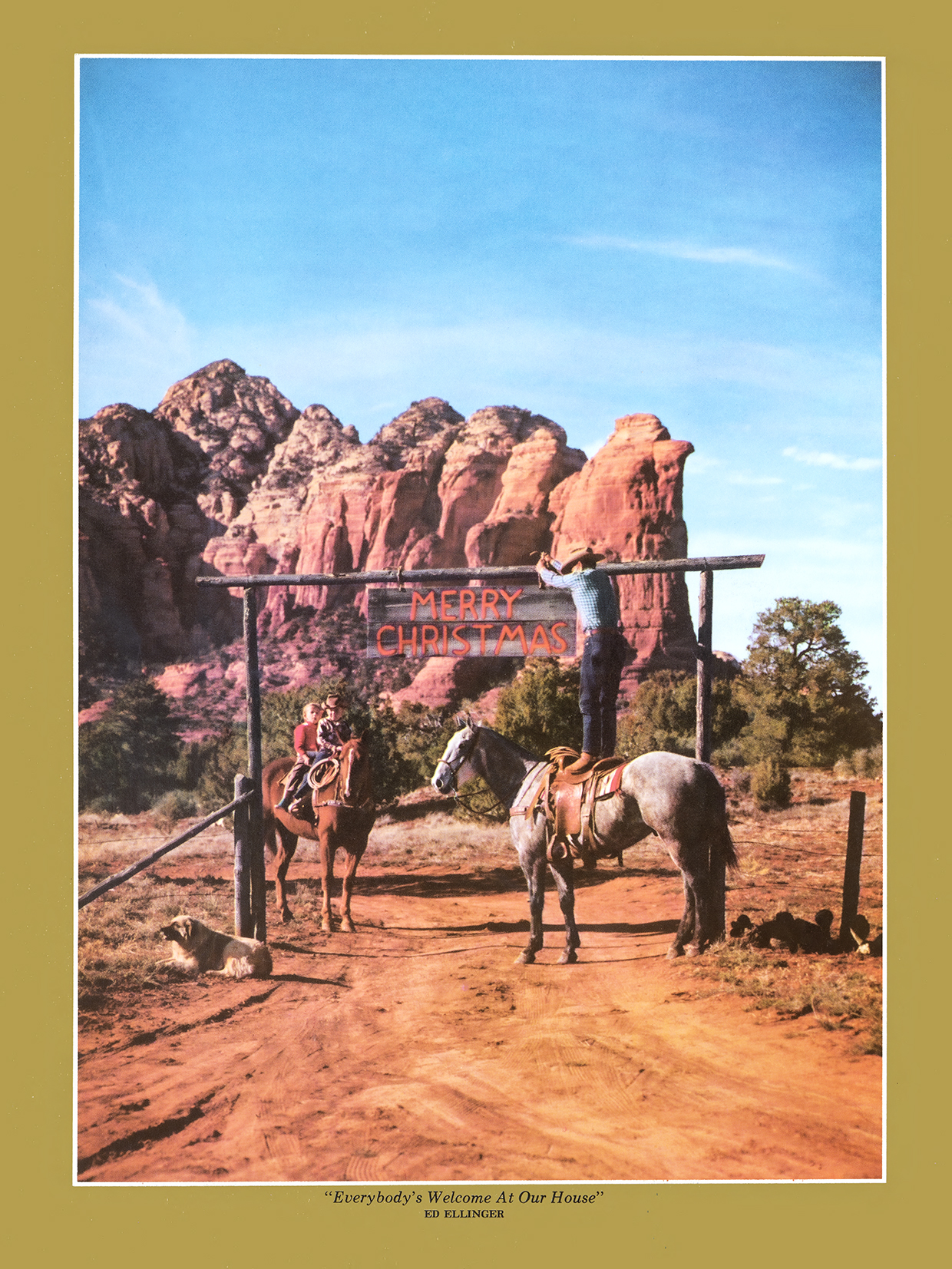

I asked Paul Thompson about the cowboy in the photograph. I figured if anyone knew his name, it would be Paul. His grandfather, Jim Thompson, was one of the first European settlers in Sedona — he homesteaded Indian Gardens in Oak Creek Canyon in 1876.

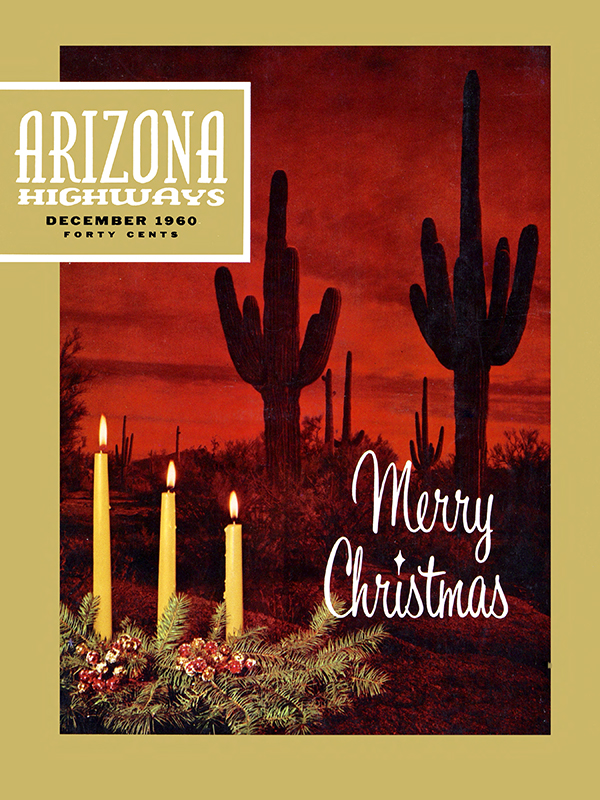

Paul wasn’t sure about the cowboy, or the two young children on the horse next to him, but he said the gate was at the north end of what used to be Sedona’s first Old West movie set, which was built in the 1940s. Ed Ellinger, who made the photograph, owned the Saddlerock Ranch, a landmark property located a stone’s throw to the south.

Turns out, the man hanging the sign was Hank Burris, a horseman from Sedona. His son, Norman, is sitting on the front of the horse. And behind him is Marquetta Kilgore, a friend of the Burris family. The image was used on the Ellingers’ Christmas card in the late 1950s. Most likely, Arizona Highways would have been on the Ellingers’ Christmas card list — Mr. Ellinger was a contributor — and that’s probably how our editor discovered the photo, which we published on the back cover of our December 1960 issue.

It’s one of two treasures in that issue. The second is a poem.

Squire Omar Barker, affectionately known as “S.O.B.,” thought of himself as “a cowboy’s poet, not a cowboy poet.” He was humble. And prolific. At one point, he estimated that he’d written and published more than 2,000 poems, 1,500 fiction stories and 1,200 nonfiction articles. There are several books with his byline, including a cookbook titled The Cattleman’s Steak Book. And he was a regular contributor to The Saturday Evening Post, Field and Stream and The New York Times. His first piece for us was a poem titled Main Street West, which ran in our July 1952 issue. Eight years later, in December 1960, we published his best-known poem, A Cowboy’s Christmas Prayer, which first appeared in a book titled Songs of the Saddlemen.

After we published the prayer, the poet — a native of Las Vegas, New Mexico — sent us a letter.

“Many thanks for your kind letter telling me of the fine reception to my poem in your December issue,” he wrote. “Unquestionably it was your beautiful and dramatic illustration of A Cowboy’s Christmas Prayer that won such widespread attention for the poem. You may be sure I appreciate the fine presentation you gave it.

“Yes, the Ernie Ford people phoned for permission to have Ernie read it on his Christmas program and paid a very decent fee. Others who phoned for permission to reprint or broadcast, after seeing Arizona Highways, included: a TV station at the University of Texas; Cattleman Magazine; the Buckhorn Guest Ranch (for Christmas cards); a women’s organization in Texas; the M Q Ranch in Osteen, Florida; a savings and loan association in Fillmore, California; and several others I can’t recall at the moment. The poem was read in church in Rifle, Colorado; Kerrville, Texas; and Las Vegas, New Mexico. Ernie Ernenwein, editor of our Western Writers of America Roundup, put in his word to reprint it next December. All just goes to prove that Arizona Highways does get around — and gets read.”

Twelve months later, we published A Cowboy’s Prayer, a poem by Badger Clark, who was Arizona’s preeminent cowboy poet — he epitomized the genre. Mr. Carlson was drawn to poets and poetry. He even ran a poem on our front cover. In December 1965. It was written by J.T. Benoit.

Dear magazine, go upon your way

Over mountain, plain or sea.

God bless all who speed your flight

To where I wish you to be.

And bless all those beneath the roof

where I would have you rest:

But bless even more the one to whom

This magazine is addressed.

Sylvia Lewis Kinney, whose daughter lived next door to Mr. Carlson and his wife, was one of our editor’s favorite poets. In that 1965 issue, we published two of her wonderful poems. The first, Desert Christmas, playfully compares Bethlehem to the arid Southwest. The second, which appeared on the inside back cover, is titled Merry Christmas Tree:

I long for a Christmas tree that’s pink,

Or a Christmas tree that’s white;

I long for baubles that gleam and wink

In colors of pure delight.

A smooth sophisticated tree

Would satisfy the soul of me.

But such is not the case. I mean

We have to have a tree that’s GREEN!

The children and their simple father

Together raise an annual bother

That shuts up any competition,

Hence I must quash my real ambition

To have a tree as starched as lace

And delicate with festive grace.

So off we go each year to see

And measure every Christmas tree

On every single salesman’s lot

Until at last we’ve finally got

The biggest, greenest tree in town.

(I put it up. I take it down.)

The Carlsons’ Christmas tree would have been set up in the narrow living room of their beautiful home, which was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Being home for the holidays was especially important to our editor. He wished that for everyone, and wrote about it in a short essay.

“Blessings on your house,” the piece begins. “May there be peace within it, and good cheer. May these modest pages add a note of color to your house and bring you a friendly greeting from others far away.

“May there be joy in your house, and love and contentment. May the lights in your window be gay lights, bright and merry lights, full of warmth and happiness, and may they proclaim to all the world that those who live in your house are humble and thankful before God and serene in their own little worlds.

“May there be a friendly fire in your house and good things cooking in the kitchen. May the table you set be a full table and those around it near and dear to you.

“May there be laughter in your house, the laughter that comes from a full heart, kindly laughter that cheers the lonely passerby who passes through your street, so that he feels better, warmed by the laughter from your house. May your house be a house whose well-being brings a feeling of well-being to your neighbor’s house, and makes the whole neighborhood better because your house is there.

“Blessings on your house and all the people in it.”