It was early 1996, and Bob Waldmire was living in Hackberry, along Northwestern Arizona’s stretch of Historic Route 66, and running his revived Hackberry General Store. To those who’d followed his career as a wandering artist, a spot along the Mother Road, his most enduring muse, seemed an ideal habitat. But Waldmire was coming to a realization, he recalled years later: “This was not the place where I wanted to live out my life.”

A mountain range on the other side of the state was calling to him, as it had for a quarter-century. In the 1999 edition of the annual recap he dubbed the Old 66 Dispatch, Waldmire included one of his signature pen-and-ink drawings of his next destination.

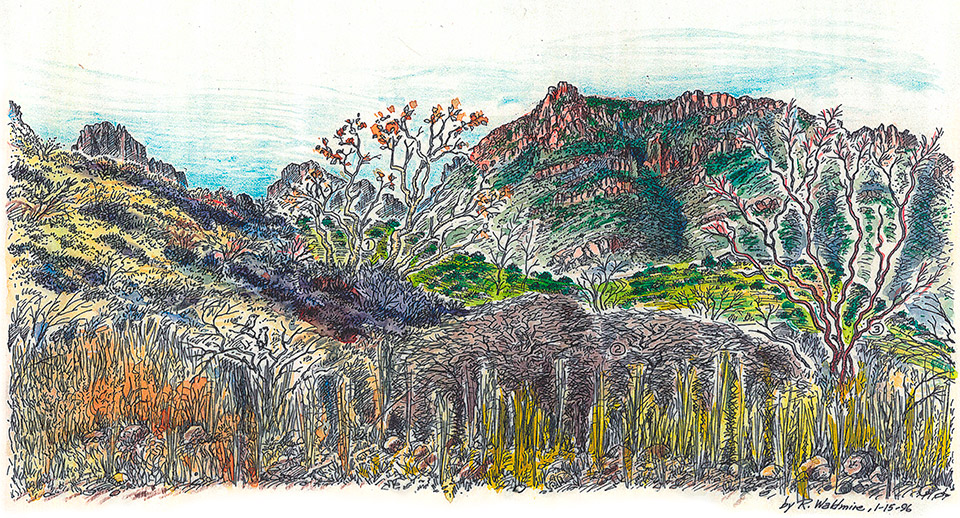

“This is my ‘future homestead,’ on the eastern slope of the Chiricahua Mountains,” he wrote. “This mountain range enchanted me on my very first visit, during the summer of 1972. In short order, I decided this was the place I wanted to ‘end up’ in — to retire to when my traveling days were done. I returned many times over the years, making friends there, camping, exploring, drawing.”

Drawing. He was always drawing. And when he finally relocated to his homestead near Portal, he set about portraying the beauty that had drawn him there in a way that only he could. “He knew this was a special area,” says Mitch Webster, the longtime owner of the Portal Peak Lodge. “And I get it. I’ve lived here for almost 30 years, and I forget about it sometimes, and then I look up and go: ‘Wow. Are you seeing this?’ ”

In a way, Route 66 was the family business for Waldmire, who was born in St. Louis in 1945 but grew up in Springfield, Illinois, right along the Mother Road. His father, Ed, was among many restaurateurs who’ve laid claim to the invention of an American staple: the corn dog. Inspired by a sandwich he’d seen in Oklahoma, Ed created the “Cozy Dog,” which he started selling in 1946 before opening the Cozy Drive-In along Route 66 in 1949.

Ed’s five sons all worked at the restaurant, and even though Waldmire later became a vegetarian, he remembered his time as a corn dog scion fondly — and as the genesis of his career as an artist. “That’s really where I got my start,” he told University of New Mexico professor David Dunaway in 2007. “My dad would pay me to do a lot of the graphics that he would otherwise have to pay a professional a lot more money [to do]. And my dad didn’t care whether it looked professional or not, as long as it was legible.”

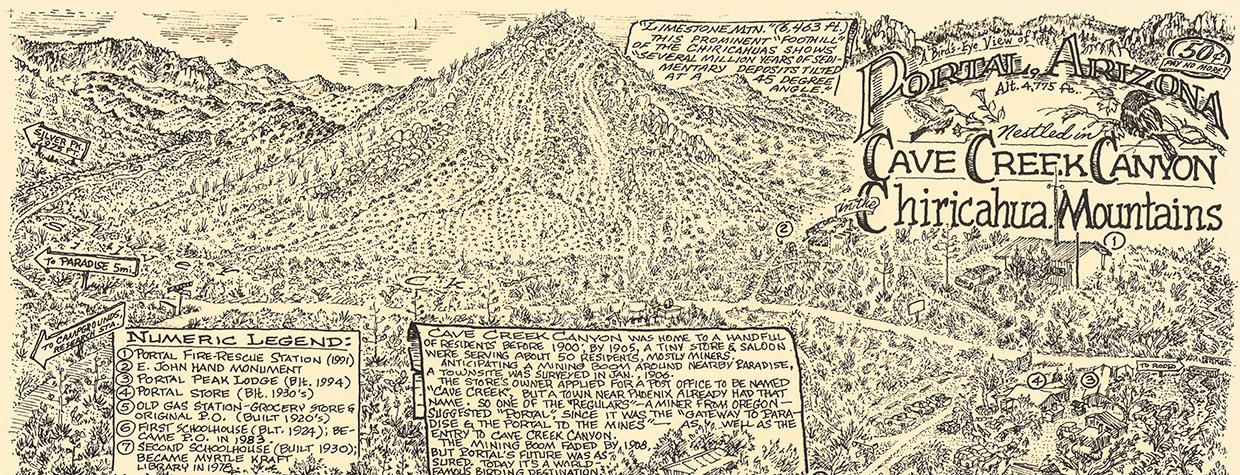

He kept drawing while attending college at Southern Illinois University, then hit the road to illustrate what he saw and sell his work to whomever he could. Among his more ambitious pen-and-ink creations are poster-size maps of the cities and states he visited. And although a picture might be worth a thousand words, Waldmire clearly didn’t want to risk it. Take his 1983 map of Arizona: Surrounding his inset drawings — a peregrine falcon, a stand of saguaros, a North Rim view of the Grand Canyon — are countless meticulously researched facts about the state, all in Waldmire’s trademark block lettering and with a socially and environmentally conscious spin.

“Two men share space on this poster,” he wrote, referring to portraits of explorer John Wesley Powell and Apache leader Cochise. “One [was] of a people who lived in this place long before the other came along … but both these men shared a reverent awe and respect for their surroundings. So, it is in this spirit of reverent awe that I dedicate this poster to all efforts to preserve the integrity of the natural history in the beautiful state of Arizona. For the Earth, Robert Waldmire.”

Between drawings and words, there isn’t a square inch to spare on Waldmire’s posters, and he wouldn’t have had it any other way. “Most of my early calendar posters were 25 inches across and 38 inches tall,” he told Dunaway. “That’s a lot of room to fill up, so I was able to get a few hundred thousand strokes and draw maybe 50 or 60 different buildings and little roads, and print these little quotes.” A former girlfriend, he recalled, urged him to leave some breathing room. His response: “No, that’s wasted space! I’ve got to fill it up!”

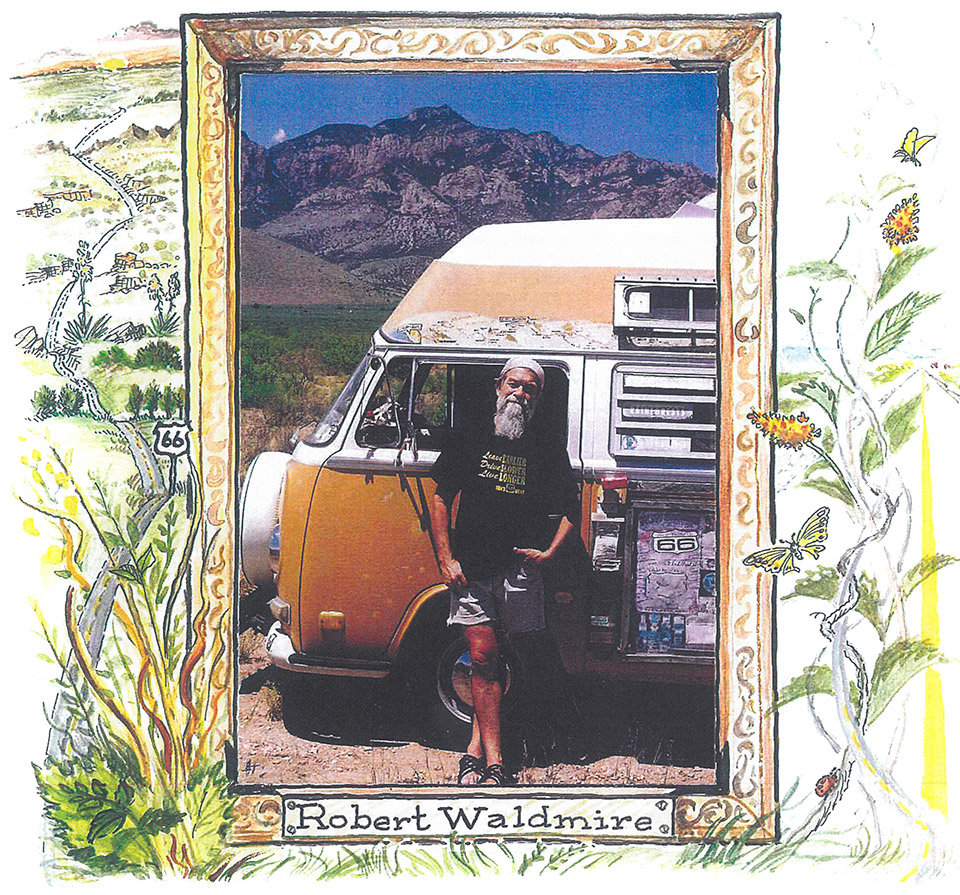

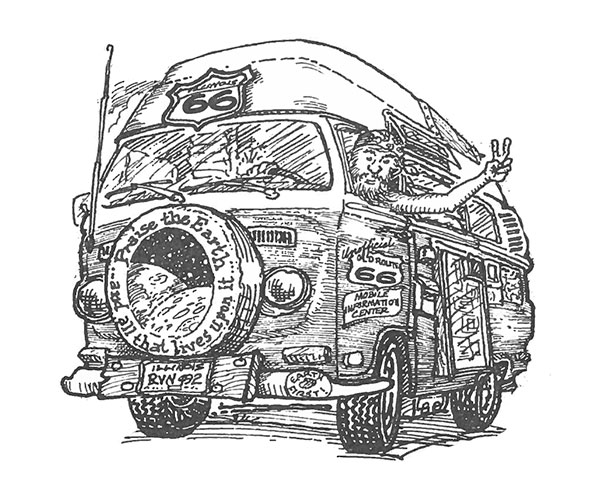

From 1970 to the early ’80s, Waldmire drifted around the country in his Volkswagen station wagon, ultimately making posters of 34 cities in 15 states, including Tempe and Bisbee in Arizona. Later, he bought the 1972 VW van that became his home on wheels. Route 66 caught his attention as he passed through Arizona in 1987, and he spent the next four and a half years creating a Route 66 map, a project that coincided with efforts to preserve and promote the recently decommissioned Mother Road.

Waldmire sold maps and postcards of his drawings up and down the route, eventually becoming so closely associated with it that Fillmore, the easygoing VW van in the Route 66-inspired Pixar film Cars, was based on him. As Waldmire told it, the character would have been named after him, too, if not for his hesitation about his name appearing on Happy Meal toys. (“That’s sort of true,” his brother Buz says.)

Settling down in Hackberry, Waldmire bought and reopened a roadside store that dates to the 1930s. In his five years there, he welcomed an estimated 30,000 visitors from all 50 states and more than 60 countries. But something was gnawing at him. “It became clear that living on the edge of a high-speed highway, full time, was not for me,” he wrote, “and witnessing a rock quarry being developed ‘in my backyard’ … lent urgency to my need to move on.”

Waldmire sold the Hackberry property and bought 40 acres on the east side of the Chiricahuas, intending to split time between there and Illinois. He pledged not to abandon Route 66, telling readers of the Old 66 Dispatch that they’d find him along the road from time to time. But he was ready, he added, to start “my new life as an ex-icon.”

"I began to sense the full import of the magnificent solitude of this place,” Waldmire wrote in 2000, soon after he arrived at his new home. “The immensity of the view — in all directions — and the long periods of utter silence can be overwhelming. No highways or trains here, in stark contrast to the old 66 visitor center.” A couple of years later, he recounted a “wonderful, wet, productive and relaxing three-week stay” during the monsoon: “Each afternoon, spectacular thunderheads would form over the Chiricahuas and move out over the San Simon Valley, bestowing blessed rain.”

Using his off-the-grid homestead — which eventually included a double-wide trailer, a windmill and a water tower — as his base, Waldmire set about portraying Southeastern Arizona in his trademark style. His love of old roads attracted him to the former U.S. Route 80, which in Arizona is now a state route that cuts around the Chiricahuas.

In a series of postcards dubbed Old U.S. 80 Scenes, Waldmire depicted the towns along the route, including Tombstone, Bisbee and Douglas. For one postcard of the latter, the historic Gadsden Hotel was the focal point, while the text touted the area’s architecture and adobe homes. “There is much to see in the Douglas region,” Waldmire wrote, “so when you visit, treat yourself and plan to stay awhile.”

The irrepressible nomad had trouble following his own advice, frequently heading north for Route 66 events or back to the Midwest during the warmer months. And one such trip, early on, landed him in minor legal trouble: In March 2000, Waldmire discovered a pair of Western diamondback rattlesnakes on his property. He decided to take them back to Springfield and display them in a terrarium at the Cozy Drive-In, then return them to his homestead and release them in the fall. But the Illinois Department of Natural Resources seized the snakes, and in lieu of a fine, Waldmire created illustrations for local wildlife refuges.

A more damaging setback happened in 2006, when thieves broke into Waldmire’s homestead while he was away. “This incident brings me another giant step closer to retirement from the road,” he wrote that year. “No more long trips away from my place — until I have someone on the place so it is protected.”

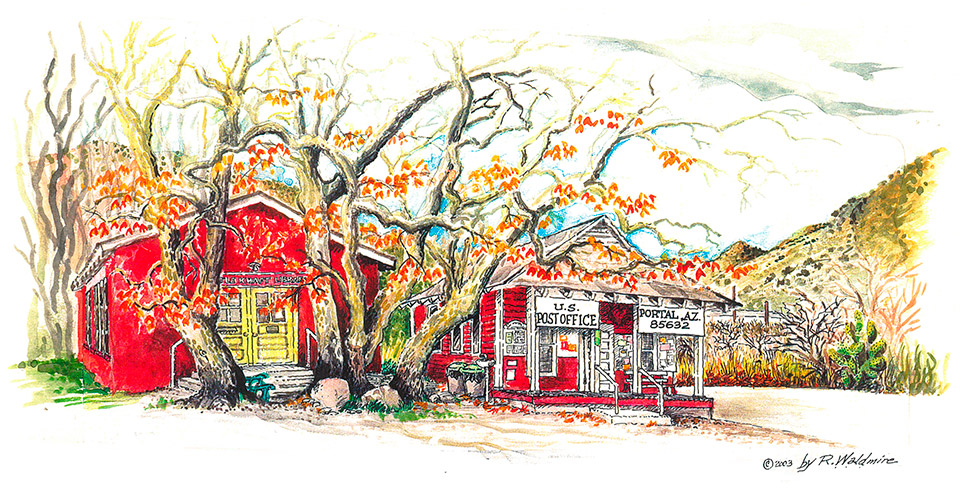

Closer to home, Waldmire made postcard drawings of his beloved Chiricahuas as part of a series he called Sky Island Scenes. Along with landscapes of Arizona sycamores and Silver Peak, he depicted a pair of historic buildings in Portal, just northwest of his homestead. The latter, along with studies of the Bisbee Coffee Co. and other area businesses, displayed a late-career evolution: “His main medium is still India ink, but he is learning watercolor,” he noted in a short bio he wrote in the third person.

Webster and his wife, Loni, bought the Portal Peak Lodge, along with its restaurant and store, in 2003, and Webster quickly got to know Waldmire well. “He’d come and drink coffee and draw all day,” he recalls, and he’d often park his van in the parking lot and sleep there to have easy access to caffeine in the morning. “I always told him he was the hardest-working hippie,” Webster says with a laugh.

Webster was 28 when he bought the business, and he says he quickly saw he was in over his head. Waldmire saw it, too, and leaned on his drive-in experience to help the family through the early years. “He would jump back there and wash dishes, and he just slowly became part of our family,” Webster says. “He was just a cool cat to be around.”

Although he was a hippie to the core, Waldmire was able to make friends with anyone. Webster recalls an older, more conservative customer who often struck up conversations with Waldmire. “Even though they didn’t have the same belief system, they always seemed to get along,” he says. “That doesn’t seem to happen nowadays, but it did then.”

Another uncommon trait: Waldmire always insisted on charging as little as possible for his artwork. Webster recalls him complaining that the postcards he was selling at the store were priced too high, something Buz also heard about items for sale at the drive-in. But it wasn’t out of modesty, they both say. For Waldmire, the value of being an artist came from having people see the art, not from having them buy it.

“He wanted to share his message,” Webster says, noting that so many of Waldmire’s pieces are filled with words he hoped people would read — even if they needed a magnifying glass to do it. “I think he really wanted people to have them,” he adds — and beyond that, “He just wanted enough to get more gas.”

For those who knew Waldmire well, it might have been obvious. For others, the 2008 edition of the Old 66 Dispatch was a clue. The pen lines were less precise, the block lettering looser, the words not as numerous. “I’ve plenty to do on countless projects and am happily ensconced here for the remainder of winter and well into spring,” Waldmire wrote above a simple drawing of his home. “So, till next time, all the best to all.”

“Next time” never came. Waldmire had colon cancer, and when he’d been diagnosed years earlier, he’d declined treatment. His health failing, he bade farewell to his mountain paradise and returned to Illinois. Or most of him did. “Half of my heart is here,” he told the Chicago Tribune in early November 2009. “And half is in the Chiricahuas.”

The next month, after one last art show at the Cozy Drive-In, Waldmire died at age 64. His VW van went to a Route 66 museum in Pontiac, Illinois, and his ashes were split among the family plot, both ends of the Mother Road and his Arizona homestead. His art lives on, but so does the impression he made on those who knew him best. For Webster — who still has one of his friend’s trailers sitting outside the lodge — those memories mean a lot.

“I miss him,” he says. “We were just a bunch of young kids, and he was kind of like a cheerleader for us. And I want to share [with him] how much I’ve done here, because he saw it when we were going under every year and barely making it, and we didn’t know if we were going to go out of business the next week. He saw all that. So, I really know what he did for me.”

Given the millions of words Waldmire committed to paper, it’s hard to choose one passage that sums him up. But something he wrote on August 5, 2008 — a day that had included a long drawing session, a chance encounter with an old friend, and a visit from an affable stray cat on Oklahoma’s stretch of Route 66 — comes close.

“As I travel so freely along my path through life, interacting with so many others along the way who are mostly ‘stuck’ where they are, my empathy for my fellow humans continues to grow,” he wrote. “Like it or not, we’re all intimately connected in this human family. … So my job — besides drawing — will continue to be being cheerful to all others I encounter, offering a wave, a nod, a smile, to lend an ear or a shoulder to cry on. Only in doing so can I have a clear conscience, as I continue to luxuriate in this rare freedom so few others have.

“Affectionately, Bob Waldmire.”

To see more of Bob Waldmire’s art or purchase posters, postcards or other items, visit bobwaldmire.com.