Jay Dusard will settle for the chile relleno, he supposes. The enchiladas he’s loved for years are no longer on the menu at the Gadsden Hotel’s lobby restaurant.

The hotel, it seems, is a little bit different now. The border town of Douglas is different, too. So many things are. And that’s OK with Dusard, so long as he has his horses and his memories. And his photographs. And some Mexican food from time to time.

Dusard wears his fawn-colored felt hat when we meet in the hotel lobby. It is a Tuesday, mid-December, and the leaves cling to the trees outside as though they’re not quite ready for desert winter. Inside, the halls are decked for Christmas.

“Isn’t it just beautiful?” Dusard asks.

It is.

A former architect who became one of the country’s foremost Western photographers, Dusard has long explored this region of the state, appreciated the angles of its mountains, the lines and spaces of its grasslands, the sometimes hardened and sometimes softened faces of its people.

So, before lunch arrives, we are scrolling through more than 50 years of photographs. His early work. His favorite work. The macro photographs he’s made of late — a piece of railroad equipment, for example — that are of particular interest to him. Dusard’s 83-year-old hands are nimble across the keyboard. Behind his glasses and underneath his graying mustache, Dusard smiles. His face is not hardened, despite the time he has spent outside in his lifetime. But it isn’t softened, either. It is the face of a man who has been a main or ancillary character in many, many stories.

Dusard stops at a particular image of the Mule Mountains that he made one afternoon after planning it for years. It was a scene he had driven past countless times, but the scene was never quite right. It is the kind of shot that a photography curator or editor would say required vision, forethought, planning. Persistence. In it, the mountains look like folded silk under a sky painted with clouds. Brushy grassland in the foreground. All angles and lines and spaces. The decisive moment.

Dusard is proud of it.

There is awe in and of it.

“I think I’ve just always had an appreciation” — there is a pause here, six, maybe seven heartbeats — “for land,” he says.

Dusard, born in St. Louis in 1937, remembers his childhood fondly. His father, a traveling salesman, moved the family all over the country — to places such as Oklahoma City; Metairie, Louisiana; Marion County, Illinois; and Hollywood, Florida.

But there was something about the River City that still sings loudest to the photographer.

“Charlie Russell was born in St. Louis,” Dusard says. “So that’s kind of a big deal to me, because he’s such an iconic figure in Western art. There’s particular pride for me, too, having been born west of the Mississippi.”

He is speaking, of course, of Charles Marion Russell, the great American painter and sculptor who long, long ago earned his spot in the Hall of Great Westerners at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City.

He is speaking, too, about his lifetime love affair with the West. With the cowboys, cowgirls, ranchers and horses who inhabit the landscape, the people who would become his ultimate subjects. To some degree, that affair began when Dusard was just a boy. Much of his childhood was spent on his grandfather’s farm, growing corn, soybeans and oats. He was driving a tractor by age 6. Later, he worked for his uncle, Harvey May, on May’s farm in Southern Illinois.

“I was a farm kid,” he remembers. “I went to one-room schools. Those were great, and I think that when we lost a lot of those, we lost some wonderful education situations. In a one-room school, there would be one teacher and a bunch of students in first through eighth grades.” One year, Dusard was the only fifth-grade student in the school.

“I really dearly loved my uncle,” he says. “He was an airplane mechanic in World War II. Once, he told me, he went 30 days in cold, wet England without a change of clothes.” As Dusard grew into a teenager, he was out mowing and helping when May’s family worked to bale up neighboring farms’ hay.

“I don’t think he had much in the way of hayfields, but he was the first person for miles to have a baler,” Dusard remembers. “It was a New Holland baler, and we’d bale hay for all of the neighbors.”

He found tenderness, and reverence, in working the land. And he developed an early appreciation for the environment.

“It’s an interesting thing to be a tractor-enabled farm kid and to be plowing ground,” Dusard says. “Of course, it’s a big no-no environmentally, but it was also the way things were done back then. I can remember being on a tractor, moving through a field, pulling a plow. You could look back and see this continuum of earth being transformed. That struck me as a rather elegant experience, but the plow really hurt the land. People will agree to that now. They might even say that it led to the Dust Bowl and the diaspora of people leaving because they couldn’t make a living on the land.”

Eventually, Dusard left, too — to study architecture at the University of Florida. He needed an arts elective and enrolled in a painting class. There, a librarian handed him a book of photographs by Aaron Siskind.

“That book really opened my eyes to the art of photography,” Dusard says, smiling. His speech has slowed a little since his stroke a few years ago, but his eyes are bright with the excitement of remembrance. “I promised myself that I’d learn photography. Maybe even get good at it.”

After college, Dusard spent two years as an engineer officer in the U.S. Army. It was a time of relative peace, and Dusard initially was stationed at Fort Hood, Texas — “smack-dab in the heart of ranch country.” In 1962, he bought his first horse, a ranch-broke 4-year-old gelding named Buck, and started spending time with rancher Will Dockery on Dockery’s cattle lease.

The following year, while stationed at Fort Polk, Louisiana, Dusard was ordered to take a fallout shelter analysis course at the University of Arizona, and he and a friend, Lieutenant Robert Lytton, made the slow drive westward. As they climbed over the lizard’s spine of the Chiricahua Mountains, they met a fire lookout who told them about a mountain lion hunter. The hunter was the rancher Warner Glenn.

On weekends thereafter, Dusard and Lytton explored Southern Arizona, arranging it so that one day they met Glenn himself. A face rendered fascinating by life on the range.

“In the morning, Bob and I rode out with Warner to range-brand some newborn calves,” Dusard recalls. “Most of the babies were lying down, so it was no test of skill for us to dab our loops on them. After a pleasant morning, as we were departing, Warner invited us to come back before we left Arizona. On our second visit, I told Warner that I was getting discharged soon, and boldly asked if a neighboring rancher might possibly take a chance on this able-bodied tenderfoot. Later, back at Fort Polk, a letter from Warner read, ‘Why don’t you come out and work for us?’ ”

The experience was so precious to the budding young ranch hand that in 2015, he, the photographer, dedicated his book Icons: Portraits 1969-2015 to Glenn’s late wife, Wendy, writing, “In the autumn of 1963, Warner and Wendy Glenn welcomed this wide-eyed pilgrim onto their ranch and into their lives of exemplary pastoralism alongside a then-peaceful international border. The richness of this experience, albeit brief, changed the trajectory of my life.”

Dusard had landed in Arizona for good. And in late 1965, he picked up an 8x10 view camera.

He started with Northern Arizona landscapes. But in 1969, the painter Rose Mary Mack, a friend of Dusard’s, asked him to make her portrait for a traveling exhibition of her work.

He had been working the landscapes, printing, making enough inroads in the field to garner the attention of the faculty at Prescott College, where he was a year into teaching when Mack’s request came. Dusard was then working with a man he calls his “true mentor”: Frederick Sommer, the artist whose images balanced on a delicate edge between reality and the experimental. Naturally, Dusard protested. He was and could only be a landscape photographer.

His subject replied, “You’ll do fine.”

So he did. Going far, far above the bar.

The resulting image wasn’t a photograph. It was a work of art. There were no lights. No reflectors. Just a portrait of the artist against a stone wall. A ladder. Her paintings. A twin bed made up, maybe for the shoot. A small rug. A perfect houseplant. A moment. In a minute. In an hour. In a day.

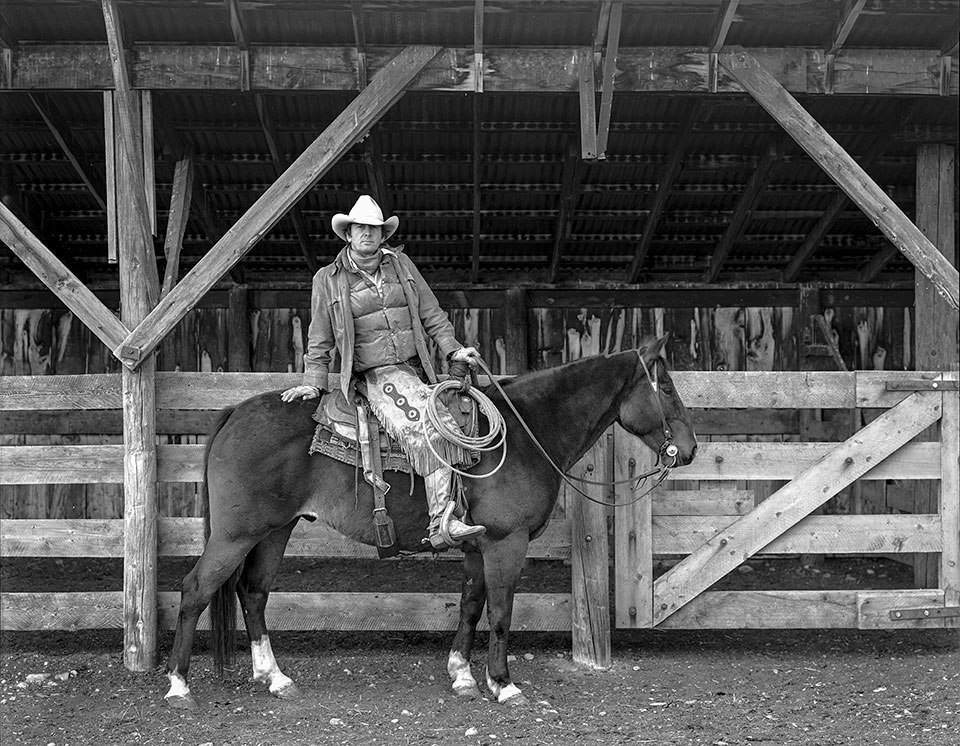

Later, Dusard would write, “My rather formal approach to photographing people in relation to settings consistent with their life and livelihood can legitimately be considered environmental portraiture — a label that exemplifies the work of the late Arnold Newman. A foolish consistency or not, practically every one of my portraits includes the entire person or persons. Nary a mugshot in the entire wagonload. Without exception, I have never used artificial lighting, not even reflectors. I invariably seek soft, revealing light — the shady side of just about everything — when my prayers for cloud cover are denied.”

For years, the Guggenheim Foundation was uninterested in Dusard’s landscapes. But then he started printing portraits — and he is, as gallerist Terry Etherton once called him, “a fanatical printer,” aided often by Carlos Mandelaveitia.

His approach to environmental portraiture and print quality piqued the foundation’s interest. And in 1981, it awarded him a fellowship.

Cloud cover guaranteed.

Over the next two years, Dusard traveled 25,000 miles, and rode and photographed at some 45 ranches, in the United States, Canada and Mexico. It was important, Dusard says, to do the same work as the men and women he was photographing: “If I was a part of it, the people

I was photographing would trust me. They’d be more comfortable when the camera came out.”

The resulting work was The North American Cowboy: A Portrait, 123 pages of delicately constructed photographs. Widely lauded by critics and contemporaries alike, the book remains a triumph of portraiture.

It’s a characterization upheld by Scott Baxter, who made Dusard’s portrait for this story and who, too, has long photographed working cowboys and cowgirls across the West. Dusard authored the foreword to Baxter’s own book, 2012’s 100 Years 100 Ranchers.

“I really think Jay’s Guggenheim work will stand the test of time,” Baxter says. “It is one of the most complete works in Western photography. That’s largely because of Jay’s persistence, his patience. He makes sure he gets it right, and I carry that with me.”

Back at the Gadsden, the chile relleno is “just fine, thank you.” The plates have been cleared, and the lunchtime crowd is thinning. Dusard slows through that highlight reel of images on his laptop. He has remembered each setup, each interaction. The stories fall out of him like salt from a shaker.

But outside, the light begins to change on the trees, and it is time for Dusard to head home. A strong handshake. A tip of that fawn-colored felt hat.

In the months since our meeting, Dusard has been writing, sending — from time to time — rich reflections about his life. In February, a 541-word essay about working with Warner Glenn arrives, its first sentence Dusard’s summary of his life and his work.

“I am not a cowboy,” he writes. “I’m a photographer with a degree in architecture and an abiding love of art.”