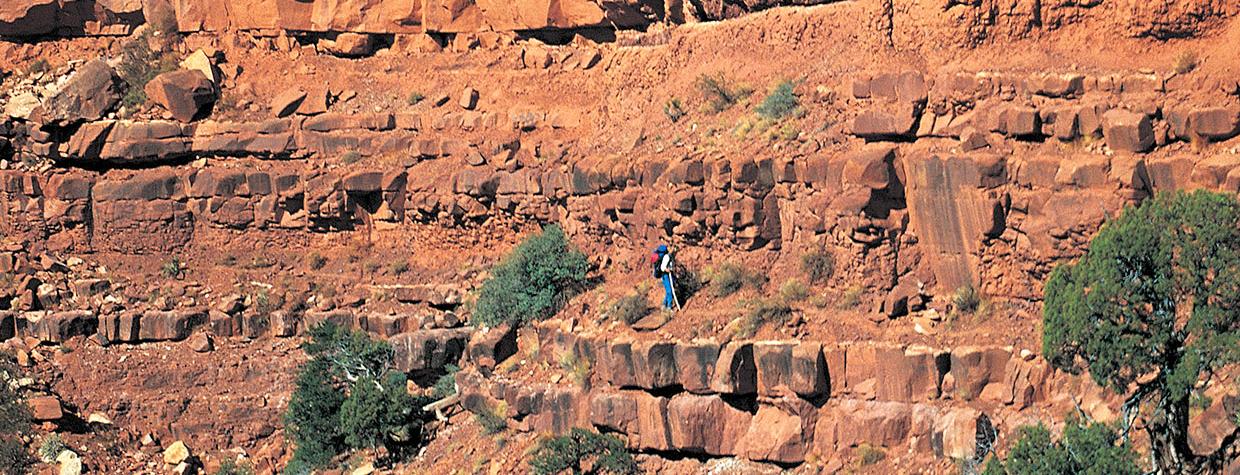

Don’t look down,” I mutter to myself as I look down. My stomach plummets at the dizzying view, and a chill shoots to my feet. I’m standing on a sloped, gravelly trail, inches from a 400-plus-foot plunge. Below, more sheer strata and screes descend like a wedding cake. My 40-pound backpack scrapes the rust-hued cliff, on my left, that rises 2,000 feet toward a dark-turquoise sky. In the distance, the “V”-shaped canyon below me opens to an immense, butte-studded landscape hiding the Colorado River in its depths. An obsidian raven floats past on a gentle updraft, its wings reflecting iridescent blue in the November Arizona sun.

I’m hiking Grand Canyon National Park’s Nankoweap Trail, an unmaintained 11-mile route that winds like a rattlesnake from the North Rim to the Colorado River. It drops nearly a vertical mile from the trailhead (7,640 feet) to the Colorado (2,760 feet). Just to reach that trailhead, at the national park boundary, requires an additional hike of 3 or 3.5 miles, depending on your route, through the rugged Saddle Mountain Wilderness. I’ve reached the section understatedly called “the scary part,” but to me, most of Nankoweap is scary. The National Park Service lists it as the Grand Canyon’s most difficult named trail, citing its deadly exposure and lack of water. Hikers are intimately close to falls for much of the cliff-tracing trail before it drops — via the steep, unstable spine of Tilted Mesa — to Nankoweap Creek. It’s akin to tightrope-walking several miles of skyscraper ledge, all with a heavy pack sloshing with 6 liters of water. The risk of a deadly fall has made Nankoweap infamous, but dehydration is the killer here. With the exception of one unreliable seep past Marion Point, the trail is dry as a sun-bleached bone until it reaches Nankoweap Creek.

I’m hiking with Dewey Surbey, my partner in misadventures since middle school, and this is our second time on Nankoweap. In March 2017, we completed the 11.5 miles down to Nankoweap Creek, but lashing weather stopped us before we could hike the final 3 miles to the Colorado River. Not satisfied with almost making it to the river, we immediately put in for a five-day permit for November with the park’s backcountry office. Eight months later, moody skies again threaten us as we teeter along the edge.

During the winter of 1882-83, geologists John Wesley Powell and Charles Walcott oversaw the creation of Nankoweap Trail to enable them to explore and study the Canyon’s geology. Improving on an old Native American route, they and a team of men and mules built the 1,200-foot switchback down to the Redwall limestone layer from Saddle Mountain in today’s Kaibab National Forest. They then traced the thin ridge around Marion Point and Tilted Mesa before the sketchy descent to Nankoweap Creek to access Butte Fault, the Chuar Group and other significant formations. Powell had already gained fame, in 1869, for leading the first team down the Colorado River through the Canyon. He would go on to serve as the second director of the U.S. Geological Survey, with Walcott succeeding him. After their study, Nankoweap was largely forgotten.

I became enthralled with backpacking the Canyon years ago and have completed many of its trails. But tucked into the northeast corner of my maps was lonesome Nankoweap, the only official North Rim-to-river trail besides North Kaibab. Any scant information I could find on Nankoweap included an October 1996 cover story in Arizona Highways, titled Nankoweap: The Most Difficult Trail in the Grand Canyon, in which the unnerved writer, Gail Dudley, turned back — a not-uncommon decision along the trail. Other articles detailed deaths here, mostly from heatstroke. When I’d ask park rangers about Nankoweap, they’d speak of it in reverent tones and warn me of its dangers, like sea captains describing some mythical beast. Extreme exposure, no water, unmaintained, expert hikers only. But it leads to a view of the Colorado River usually afforded only rafters, and its 1,000-year-old Ancestral Puebloan granaries, stoically overlooking Marble Canyon, spoke to my passion of archaeology. I had to do it.

Focused on the “scary part,” I swallow my fear, clear my mind and carefully plant one boot in front of the other. The gravel-covered trail slopes toward the drop just inches away from my boots. I resist the urge to speed up, and I do my best to clear my head of anything other than making perfect steps. Down the trail, I hear the reassuring tapping of Dewey’s hiking poles.

“I thought that would be easier this time around,” he says, wide-eyed.

“Yeah,” I exhale. The fall afternoon is a mix of warm sun and chilly breezes. We allow ourselves a few moments to scan the Canyon’s majesty, spanning all the way to the horizon, before returning our focus to the trail. Nankoweap is as mentally exhausting as it is physically so, and daydreaming here can be fatal. With its narrow confines, the trail can trigger feelings of claustrophobia. You must maintain constant concentration: What would be a simple stumble on another trail could send you over the edge on Nankoweap. In some places, you’d fall a survivable 10 to 20 feet before hitting a short slope that rolls to another drop. Hopefully, you could grab a twisted piñon or juniper before sliding off again. If you weren’t too injured, you’d have to figure out how to climb back up to the trail. In most places, though, it’s a drop of 100 feet or more.

There are only two places along the 8 miles from the trailhead to Nankoweap Creek that are wide enough to take off your pack and rest: Marion Point and Tilted Mesa. We take a quick break at Marion Point, a thin peninsula that juts over the Canyon. We relax in the shade of a lone piñon and take in the view of Point Imperial and Mount Hayden before resuming our cautious trek to Tilted Mesa, some three hours away.

Dewey and I are largely silent on Nankoweap, and our fears have morphed into a mix of calm exhilaration and electric boredom. Focusing so intently on the trail for so long gets tedious, but we dare not let our minds wander, for fear of making a mistake. Except for the constant tapping of our hiking poles, we hear no sounds on Nankoweap.

Dusty pastels begin to layer the evening sky like a sand painting as we reach Tilted Mesa, and we catch our first glimpse of the Colorado far below. We had planned to camp here but decide to race the sun to Nankoweap Creek, 3 miles away, to make up for several delays. We pass our packs to one another as we climb down several 10-foot drops to the mesa 2,200 feet above the Canyon floor. From here, the trail descends a spine of loose Bright Angel shale, its screes sloping into deep side canyons hidden in purple shadows. The trail is like oiled marbles on a 30-degree slope, and our hiking poles constantly test the ground ahead of us like cave cricket antennae. Loose pieces of Bright Angel shale sound like broken crystal as they skitter into the void.

I’m extra cautious — last time, I slipped here, breaking a pole and sliding toward a long fall into Little Nankoweap Canyon before stopping myself. The brightest stars start piercing the salmon sky, and soon we’re following tunnels of light cast by our headlamps through the inky blackness of the Grand Canyon. When we reach a dry streambed, it feels strange and dangerous to walk normally again without fear of falling. Before long, a green curtain of willows glows in our headlamps, and we know we’ve reached Nankoweap Creek. It’s 10 p.m., and after setting camp and wolfing down a dinner of freeze-dried beef stroganoff, we collapse into our sleeping bags. A meteor flashes yellow across the star-strewn sky before I drift off, but I don’t bother making a wish. We’ve completed the hardest part of Nankoweap again, and tomorrow, we’ll step into the Colorado River and see the granaries in person.

At dawn, through cracked eyes, I see bruised clouds, singed red, hanging low over us, threatening rain or snow flurries. Nankoweap Canyon, where we’re camped along Nankoweap Creek, is still cold and dark.

“That doesn’t look good,” Dewey mumbles from deep inside his mummy bag.

I boil water for coffee and think about my next move. It’s 3 miles to the river and granaries — about a two-hour hike through level, rocky terrain studded with mesquites along the creek. If it’s a downpour, the creek could swell. Plus, I wouldn’t want to attempt the steep trail that switchbacks up Nankoweap Butte to the granaries, some 500 feet above the river. I’ve learned to never push my luck in the Grand Canyon, but we’ve come too far to be thwarted again. With a day left on our permit, it’s now or never.

“I’m going to go for it now and catch the light,” I say as I stuff my camera into my daypack. Dewey decides to fix a problematic boot and come down later.

I pull out my rain shell and head downstream. River-smoothed rocks ranging in size from cobblestones to bowling balls pave the way, and for the next two hours, light rain falls off and on, but it’s nothing torrential. As if on cue, the clouds begin to lift as I see the green of the riverbank in the distance. The mouth of Nankoweap Canyon opens wide, and the trail leads to the south, around Nankoweap Butte. Cresting a steep rise and scanning the towering butte, I spot the granaries and am awash in a sense of completion and humility. The granaries blend into the cliff face high above the river, and I imagine farmers working cornfields below. Today, a millennium later, I’m the only human here.

I trudge up the cliff-hugging switchback trail to the base of the granaries, 50 stories above the river. A thin ledge runs beneath two of the structures, and inattentiveness could send me falling a good 50 feet. Reaching the base of the granaries, I marvel at their construction of tight rock and mortar in a protective alcove. Small openings have long since lost their coverings. I envision people hiking up the switchback with heavy baskets filled with corn and climbing above the precarious ledge to stack cobs inside the granaries. Their lives depended on protecting their crops from flooding, rodents and possibly other humans. Below, the wide Colorado glows silver in the sunlight as it flows south. I take my photos and lose track of time sitting below centuries-old ruins in a 6 million-year-old landscape.

Sunlight crawls around the butte and onto the granaries, and I take a last look at the ruins before starting down to the river. The view looking south, as the water flows toward Desert View Watchtower some 20 miles away, is more a Thomas Moran painting than real life — the scene is too perfect. Reaching a sandy beach, I take my boots off and step into the cold water, relishing finally completing Nankoweap Trail to the Colorado River. Alone at the bottom of the Grand Canyon, I feel as small as a single drop of water in the timeless Colorado, and I couldn’t be happier.

If You Go

Directions: To reach the Nankoweap Trail during the North Rim’s operating season (mid-May through mid-October), from Jacob Lake, go south on State Route 67 (North Rim Parkway) for 27 miles to Forest Road 611. Turn left (east) onto FR 611 and continue 1.4 miles to Forest Road 610. Turn right onto FR 610 and continue 12.3 miles to the Upper Saddle Mountain Trailhead. From there, it’s a 3-mile hike east through the Saddle Mountain Wilderness to the Nankoweap Trailhead. That route is inaccessible when SR 67 closes due to snow, but the trailhead can also be reached year-round via a 3.5-mile hike from Forest Road 8910 (Buffalo Ranch Road). From Jacob Lake, go east on U.S. Route 89A for 19.5 miles to FR 8910. Turn right (south) onto FR 8910 and continue 23.5 miles to a fork. Bear right and continue 4 miles to the trailhead. While the hike from this trailhead is slightly longer, some hikers prefer it because the return trip is downhill. Both routes are accessible in a standard sedan in good weather, although a high-clearance vehicle is recommended.

Camping: Overnight camping outside of developed sites in Grand Canyon National Park requires a backcountry permit.

Warning: Hikers should be prepared for extreme temperatures, particularly at the Canyon’s lower elevations in summer and its higher elevations in winter; for the trail’s lack of shade and abundance of dangerous drop-offs; and for sudden rain or snow from fast-moving storms. Carry at least 1.5 gallons (about 6 liters) of water. There is no reliable water until you reach Nankoweap Creek; however, just past Marion Point is a small, unreliable seep that can be used in emergencies. Water collected there or at Nankoweap Creek must be filtered. This trail should be attempted only by expert hikers who do not struggle with vertigo or a fear of heights.

Information: Grand Canyon Backcountry Information Center, 928-638-7875 or www.nps.gov/grca. The Nankoweap Trail location is AE9.