Here in Arizona, as “the swift seasons roll” to bring Autumn leaves tumbling round our ears, I am reminded anew of the poet who urged America to know herself. Where else has that ringing challenge, meant for all of us to follow — “I celebrate myself, and sing myself” — been so well answered? Walt Whitman, if I read his lines aright, would have applauded a celebration, impossible in his time but so right now, proclaiming in a universal language even the unlettered may read, if he but has eyes to see the singing color, spread out on page after page of Arizona’s own month-by-month “book.”

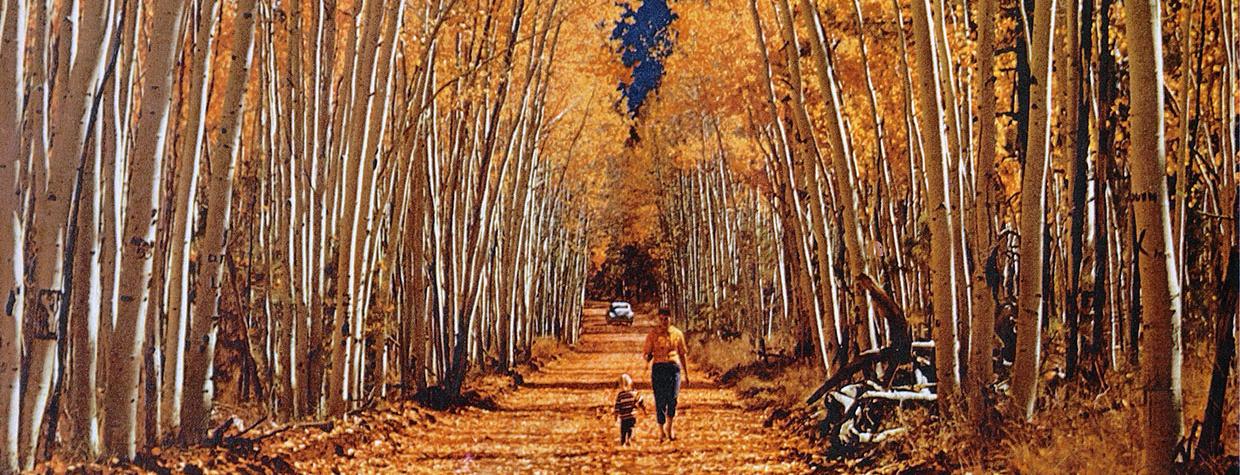

Forget, for the moment, that you can read these words, though printed in a language of which half the world now makes some use. Perhaps you belong to the other half and cannot! (For this is, after all, a magazine seldom discarded, but, rather, is passed on from hand to hand often around the world.) You may be doing just what I am about to suggest, without my asking it. Forget the printed page and look again at the pictures of bright October in Arizona. Wander from cover to colored cover. Opening the doorway of page after page, walk right on into vistas of shady forest or along a desert wash under the glowing cottonwood trees. Celebrate, with each new scene, the beauty of this world into which you are invited, whoever and wherever you are. If you will bring your whole self, the clean spice of pine woods will come out to meet your nostrils; the rustle of leaves will be audible to your ears.

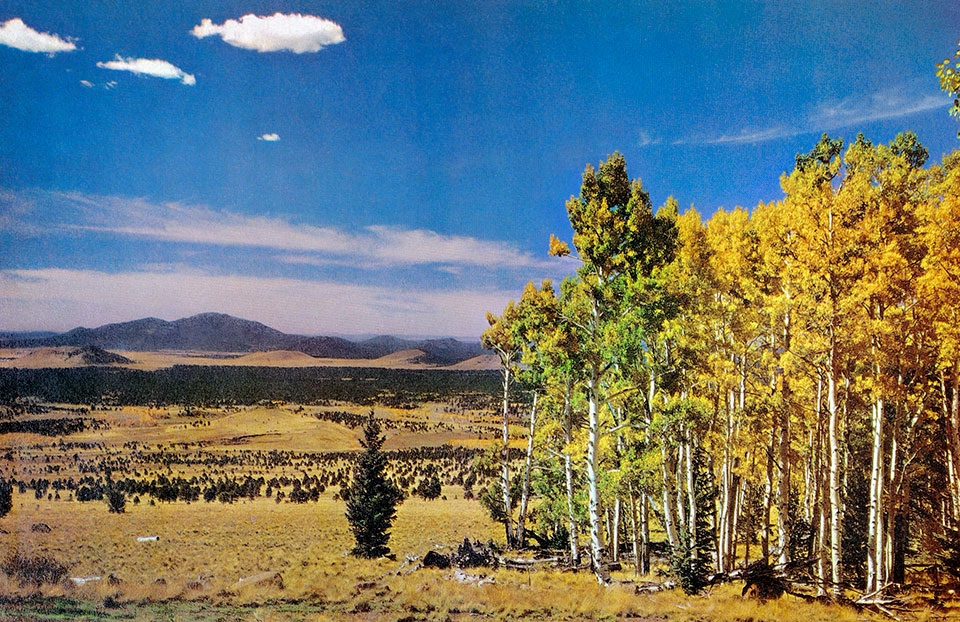

What a glowing world it is. Red cliffs, probably much higher than you think, stand rooted deep in the foundations of the earth. From rims you look off into the roominess of great canyons, furnished with massive buttes designed in fundamental styles, impervious to passing fad. Mountain peaks, seen through October’s golden frames, may be climbed in a glance. There are deserts, reaching far to fringe of sharp-cut, ridged horizons, “peopled” by plants as extravagant as the landscape. It is peopled too by human figures, wondering at the scene, themselves part of the long distances, the rolling hills, all limned against the crisp clarity of air, native to this region, and sharpened by the season. Fields, rough with stubble new cut, or green with one more of the continuous crops, unroll through valleys. Cattle browse in broad meadows. What a never-never land it must look, viewed from some distant, less peaceful, serene, and gracious spot.

There is, though, an end to pictures and so, a parting of the ways. Those who can follow only what is portrayed by camera or paintbrush must stop at the turn in the road, when the printed page takes up the task of guide and celebrant. Around that final bend, where vision halts, we can assure the reader of more Autumn. On the other side of the mountain we can lead the mind’s eye to new slopes, festooned in color; canyons splendid as the one the camera saw are just past the next rise. All of Arizona’s highlights, each of Autumn’s specials, can’t be pictured in a single issue.

Now perhaps, dropping into Walt’s own element — words — we can catch up with the poet, striding along a side road, which he might expect to lead, not us into Autumn, but Autumn into us. As we match our step to his, we come upon a small bridge, built for more water than the chattering stream now commands. A path drops down to kneel at the water’s edge, and then goes on apace, heading to a private rendezvous. An unseen bird, garbling a shortened version of his spring song, warns against it, but do you mind a little mud on your shoes? It seemed to me that last inquisitive breeze carried an echo. Now a jay rebukes us with his “Thief! Thief!” when all we want to steal is a look at his hidden waterfall.

See it, over there, hanging above the bend of the stream? A few steps more and we are there. The same tale-bearing breeze, or another, lifts the skirts of the young pines and starts the aspen leaves to shocked whispering. Bushes shake out a bagful of their yellowed leaves for the water to tumble about, and the sunlight, pushing past a trunk which shaded it, picks out colored pebbles in the bottom of the creek, making one a ruby and another a black diamond.

People with more strength of character than I seem to be able to take all of this in at a single glance and be on their way. I linger in hope of spotting at least one fingerling, darting through his own cool, fluid world. There should be a frog about, waiting, like the chairman of a board-meeting, for perfect silence, before he lifts his voice. The throaty reply from the other side of their “director’s room” is always a deeper tone, but in perfect agreement. In Frog Realms, there seems never to be any difference of opinion. While the chairman makes known his decision and the vice-chairman seconds it, the water, in gay trills and splashes, with changes of rhythm and varied tempos, invents a baker’s dozen ways in which it can descend over the smallest of falls. As all these small nothings are happening, the patrolling sun has moved on, but not until we find ourselves casting an affirmative vote with the frogs.

Since aspens troupe through any western wood, at their own chosen altitudes, our wandering feet may come upon them in intimate groves as well as the lingering views from roadsides. These trees take over where long-forgotten burns laid waste the slower-growing evergreens.

Another affirmation of October’s special grace could lead us along the road to an open park, circled by darkening pines at the soft edge of the day. The sun, in lowering, floods a group of aspen trees — white limbs straight, their leaves and branches interlocked like the arms of a dancing chorus. One hardly dares snatch a glance to take in the rest of the stage: white road bending in gentle curves through a sea of grass, pine, spruce and fir, molded into somber drop, pulling the eye back to the aspens which burn and shimmer, flaring into a final burst of color, a visual clash of tympany to mark the end.

Through the succeeding hush and dimming light, phantom shadows steal from the wood’s edge: deer coming out to feed. A young buck, in the pride of his first antlers, reaches up for a mouthful of leaves and pulls down a shower of golden coins which slide from his back to entangle in the green of a little tree. They shine palely, like an arrangement of half dollars in gold foil tied to branches as a 50th wedding anniversary centerpiece.

More vignettes of fall color come to mind that we can visit, for time and distance mean nothing to the agile imagination, riffling through a drawerful of memories. We might look at a mountain slope which could have been labeled “In the White Mountains of New Hampshire” but was really in this Arizona’s White Mountains range. The foreground of meadow grass, clipped lawn-short by cattle, lapped at the forest’s edge, where the summer green was dulling. Higher, to lift and pour over foothills and descend in billows, was the potpourri of tones we had come far to see. Yellow, orange, and even red hints in the populous aspens hid their white trunks. Oaks added another red, verging on rose or tilting toward russet and frank browns. The maples — sugar, vine and scrub — were mixed with scarlet sumac and almost purple wild rose. Yet not bush or tree claimed individuality, but lent itself as single thread in many, embroidered petit point on the warp and woof of hunter’s green.

Since aspens troupe through any Western wood, at their own chosen altitudes, our wandering feet may come upon them in intimate groves as well as the lingering views from roadsides. These trees take over where long-forgotten burns laid waste the slower-growing evergreens. Not above acting as “cleanup committee,” Populus tremuloides, which in Northeastern woods pale beside their blood brothers, the birches, here reach conspicuous girth and height. Allowed a short life (half a century, at best), but a merry one, they prepare the ground for a new company of conifers. The gay show of sunny foliage in fall, climaxing months of fabricating green from yellow light and blue skies, is all but over when Autumn winds come to collect their due.

Depending on mood, the aspens may pay off, coin by single coin, loosed from a branch’s grasp, or in sudden abandon toss down a gambler’s pile upon the forest table. Then denuded branches take on the pale gray of drifting smoke, and the ground shows gold-plating, soon tarnishing to dross. If these be indeed “the melancholy days ... saddest of the year,” the “wailing winds” might protest that, in spring and summer, when they blew, the same leaves flirted and coquetted on their flattened stems, showing off pale “underslips.” Why now do they refuse to frolic, dropping instead of rebounding from a jovial busk? Well, if fall they must, the wind will harry them from white pillar to bare post, shake the stripped boles in a fury of disappointment at being defrauded of its rightful fun.

In plateau and canyon country, where surprises, any season, are the general rule, we go out of our way, as summer wanes, to find the chamisa, called rabbitbrush for its most devoted admirer. Perhaps to accommodate “Jack” and “Cottontail,” the chamisa varies its size from neat, round, almost balls of yellow to man-sized clumps which may usurp a whole landscape. At its most photogenic, bushes of it outline the turnings of a dry wash as neatly as though set out by a careful gardener. I have seen it following an ephemeral watercourse as long as the pebbled bed could be tracked over the tablelands. If the annual blossoms had not long since “mailed” their seed packets by wind or winged carriers, but were still there to lend support to the illusion, the rabbitbrush might, from afar, be taken for poppies and it be spring in cool October.

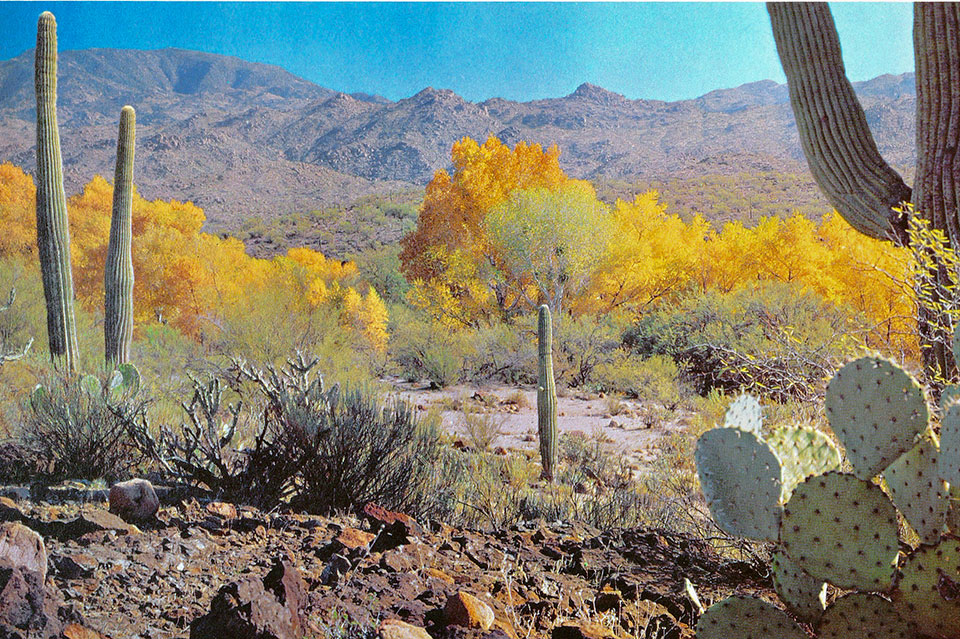

As soon as you top a rise, giving a preview of desert basin beyond, if there be a live stream, poking a way through rocky boulder and sand, an accompanying line of cottonwood trees waves invitation to shelter.

The desert is no stranger to autumn, either. If you have assumed that the ample lowlands, where the Gila and Salt River valleys rival the ancient Nile in climate and fertility, are neglected or left undecorated, the cottonwood tree will be the first to disabuse you. True, the sun has side-slipped from its high summer trail across the sky, trimming another slice from daylight hours each day, but you still choose a rock in its full glare as a bench at your peril. As soon as you top a rise, giving a preview of desert basin beyond, if there be a live stream, poking a way through rocky boulder and sand, an accompanying line of cottonwood trees waves invitation to shelter. Some spur of road, if not main thoroughfare, will head for it, as surely as to man-made hostel with letter sign, swinging gently in the breeze.

If the year be near its end (the exact date calculated by as intricate a method as IBM contrives, no doubt counting in the heartbeat of collared lizard and the smile on the face of the Lady in the Moon), the cottonwoods will tell you in one glance that Autumn is here. Seen with light flowing from behind and through the ample spread of branch and leaf, they can be as dazzling as any tree which grows. Their shade is welcome to man and any other animal lacking an underground retreat for daily siesta.

The big Fremont, or white, cottonwood towers above almost every other desert plant and scorns the subtle devices of cactus, leafless shrub or escapist annual, for either conserving water or denying itself what you might regard as “the pleasures of the table.” Its leaves are many and generous, for the parent, sprawling great trunks and limbs like an amiable giant, is a good provider. It goes unerringly to an adequate supply, not of necessity above ground all year, but still present, waiting to be tapped, below.

In the umbrella shade, a stream may be running quietly about its business, humming softly as it ferries the leaves which come sailing down like paper kites. They whirl at the touch of fellow voyageurs and gather in groups behind the slightest of twig dams before setting off again, toy flotillas bent on seeing the world beyond. If you linger in these cool “patios” the hush envelops you, and the reflected light comes where it can in shafts, as though streaming through stained glass into the nave of some great church.

Willows frequent these streams as well, a different species for a different elevation, but all yellowed in fall. Some of the slim wands will know happy reincarnation in tightly woven [Tohono O’odham] baskets, holding water without caulking, as the stems swell to make an impervious surface.

The tamarisk, familiar in the Southwest as a tall, feathery windbreak under irrigation, may never grow bigger than a shrub on its own, but big or small has a bright shade, almost orange in Autumn. Seedlings, wind-scattered or stream-borne, may make a brave start in the still-damp sand of a wash and by fall be jaunty sprigs, bending and waving to any flick of breeze. Taken together, a whole nursery — not destined to outlive a full, dry summer — gives the wash the look of having stolen some of the sun’s own gleam.

The sharp cold of night, clamping down once the sun’s back is turned, holds the brush which paints color in the leaves, out in the desert, as elsewhere. There is, though, more to the story. Chemistry holds the main key, with variables of soil content, precipitation rate, and a jolly company of contributing factors to make quality, quantity, as well as timing, as unpredictable with precision as the coming of spring flowers. Rather depressingly, we face the fact that those pretty daubs of leaves are just skeletons, ghosts of their summer selves when they grew on the tree: their cells dead, cut off from the chlorophyll supply which bestowed their greenness, now showing other colors which were present but covered, as old masterpieces have been discovered under layers of later paint. All up and down Arizona, desert, plateau and mountain country, there are unsung plants, each saying plainly: “Autumn was here” — Kilroys of the plant world.

Now another crossroad looms ahead. Those of our companions who were reading from distant armchairs must be left behind. Perhaps next year, or some tomorrow, will shrink the world enough to bring them here in person. Since Time is of the essence in our century, even those of us who like to walk — fearing that, after a few more generations of disuse, human legs may become as insignificant as the vermiform appendix — must compromise. The tourist’s equation now stands:

Limited Time + Many Miles = A Car.

Walt Whitman would still be with us, for he urged us to move with the times, and would agree, no doubt, that not a great share of Arizona’s Autumn can be covered afoot. So we will go acar. Most pleasantly, too, for the state’s ever-evolving highway system was built with that in mind: that the way might be pleasant and not merely safe; the views the finest; and always some place, not too far, to stop for the night. Look to your road map for every possible answer, with numbers to key into your particular problem. The choice is yours since you are many, coming not by any one, but diverse gateways into the state, asking: “Where does Autumn ‘grow’?”

It springs into vision first, of course, up high, where the tempo of the seasons is brisk. Leaves color in early October, and the aspens, of which we think again and again since they are first to carry the banner, are leaders of the parade, most conspicuous and most widespread. Wherever plateau or lofty slope reaches above 7,000 feet, they are apt to show. The Kaibab Plateau, swooping back up from the North Rim of the Grand Canyon (Arizona 67 is your key), is one of the great exponents of rampant color, in a hurry to make its seasonal statement before winter can bring up a white-lipped rebuttal. Not much farther south, U.S. 89 carries on to Flagstaff, where it looks toward yellow and green “posters” plastered on the slopes. Trim forest roads push in for a closer look.

At eastern gateways, on the New Mexico border (via U.S. 60, 260 and 70), travelers are admitted to the state’s biggest and most important range, the White Mountains. Here Autumn has room to lay out every shifting combination of meadow and forested background, admire her own festive beauty reflected in cupped blue lakes or set out in unexpected arrangements, caught up in orgies of yellows and reds, along hundreds of miles of mountain streams.

There are fields ready for harvest or already cleared, near little towns reveling in the time of the Harvest Moon. Picnic spots and hunters’ paradises lie away from through-roads and alongside. You may be delayed as a wild turkey flock bustles across in front of the car, to raise a clatter of falling leaves and lifting wings, as they take off, faster than camera can catch save in a blur. Deer are moving cautiously down from summer resorts, their “radar” ears combing the woods for danger. You must hunt up for yourself the hidden retreats where maple trees show off the traditional family brilliance. Still lower on the map (from U.S. 80), the Chiricahua Mountains are visible, guardians not only of rock fantasies, but the promise of color etched below peaks which can almost claim 10,000 feet of elevation.

I dare say it would take you all of the autumn season to really “do” just the highlands, along Arizona’s many roads, and deep into November or even into December to get the answer to the poet’s question: “Where do the colors of Fall go?” They flow from mountain to plateau, down canyon or over the paint-splashed cliffs, to eddy in pools and trail long streamers out into the desert.

The Santa Catalina Mountains, above Tucson’s ancient valley, wear Autumn’s badge in colors which will “run,” somewhat later, down into the desert, using such charmed routes as Sabino Canyon, where saguaro cactus sentinels are quartered on steep banks along a purling stream.

Snow may have shut the door to the North Rim on the Kaibab before the desert cottonwoods will admit that fall is come, but escalator-canyons provide smooth descent from one seasonal “floor” to another. Oak Creek Canyon, for one, though it confuses the issue by wearing variegated autumnal tints on its walls and buttes, all year long. When you come, it may be switchbacking down from winter on the rim, through Autumn-tinted forest glades, to slip into summer warmth below. Since it numbers among its forest residents such “color-makers” as oak, aspen, sycamore, maple, with cedar and pines for green ballast, mark it (on U.S. 89 Alternate) with four stars, or as many more as you can spare, for an Autumn “must.” The creek takes stairs down, as lively as the competition between plants and rocks, in creating vivid effect, and then warmed by its race, slows to a walk under the serene cottonwoods in the desert valley.

I dare say it would take you all of the autumn season to really “do” just the highlands, along Arizona’s many roads, and deep into November or even into December to get the answer to the poet’s question: “Where do the colors of Fall go?” They flow from mountain to plateau, down canyon or over the paint-splashed cliffs, to eddy in pools and trail long streamers out into the desert. By the time it is over, the night’s crispness, mild reminder of the mountain-winter’s bite, gives way to warm days already reaching ahead to spring.

I can think of no pleasanter time to be anywhere than the tag-end months of the year, in the desert. In the Patagonia Country, hard by the Mexican border (where Arizona 82 rambles leisurely from Tombstone, west to Nogales), the aftermath of early Spanish Days seems to hover in the golden light. North (on U.S. 89 to Tucson), as well as west of the highway among the Ruby Mountains, Time loses its sting. All of this southwest corner (through which U.S. 80 rushes to Yuma, and U.S. 60-70 from Phoenix to Blythe), lies in the Cottonwood Kingdom. Lakes, lazing behind the stiff-harness of dams on the Colorado River, put out tamarisk and willow spotlights, with fishing, if you need an excuse to loiter.

We would be delinquent not to mention the sprawling acres of the Navajo Reservation. You may not have yet heard that blacktop makes a flying wedge, pointing east from U.S. 89 near Cameron, and opening the whole reservation to travel in comfort. Arizona 64 points roughly north and then east, along the Navajo Trail. At Kayenta one prong of a two-tined fork strikes toward the Utah border at Monument Valley. (In Autumn I always think of one veteran cottonwood tree lording it over Tsegi-ah-tosie Canyon, deep in the Valley fastness. You can look up, dazzled by the purest gold of leaves set against dark veins of heavy branch, caught between sky and old-rose walls.)

The route to Kayenta and beyond to the Four Corners fairly drips canyons and washes, their cottonwoods showing. Tamarisk and willow flood tributaries coming down to meet road and eye. The other side of the wedge (Arizona 264) diverging at Moenkopi, through Hopiland, Keams and Steamboat canyons to Window Rock, will break the back of any hard-and-fast schedule, if the camera gets into play. Canyon de Chelly lies east and betwixt and between the two routes, on its own northbound paved road (from Ganado on Arizona 264). It has held fall festivals of color even before the Navajos claimed it for their special sanctuary, several centuries ago. Not only do the massive walls of its several-fingered gorges hold in fee the homes of an ancient people, and tamarisk, willow and cottonwood crochet patterns at their base, but there is no finer time to explore its archaeological and geological wonders than now, when the sandy floor is a firm highway and the rim drive an air-conditioned balcony for overviews.

Afoot or acar, or just fingering pages on which the colors glow, there is no doubt that Arizona this fall will be outdoing the poet. Part of this glory, if we but enter into it (and if not, why do we look or listen or travel there?), we can be of the company of the tinted leaves and declare: “I celebrate myself, and sing myself.”