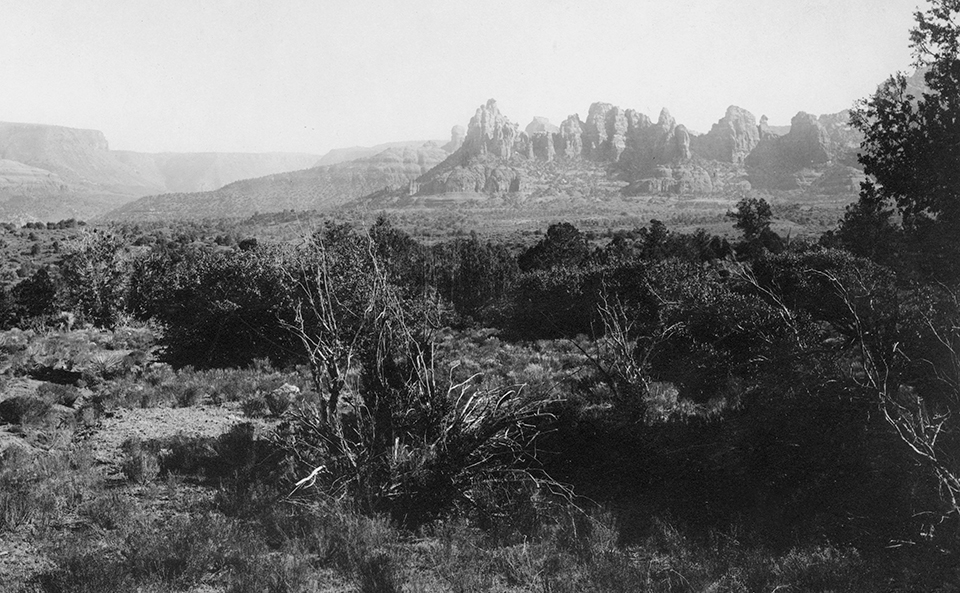

Nestled between ancient sandstone walls and shaded by centuries-old sycamores, Indian Gardens is a place deeply rooted in time. The most obvious monument to its past is the weathered stone face of Indian Gardens Oak Creek Market — a popular stop in Oak Creek Canyon for decades, and the oldest continually operated general store in the area.

But across the road stands a marker more easily overlooked. The small plaque speaks to a time when Indigenous people grew corn, beans and squash along the creek and the area’s first Anglo settler planted his own roots, helping to lay the foundation of Sedona’s modern era.

Spiritual pilgrims seeking enlightenment at Sedona’s vortexes have come to associate Sedona with the New Age. But to some, Sedona’s most revered sites are places such as these, where pioneer families settled before the turn of the 20th century, cultivating civilization in a wilderness that was as unforgiving as it was beautiful.

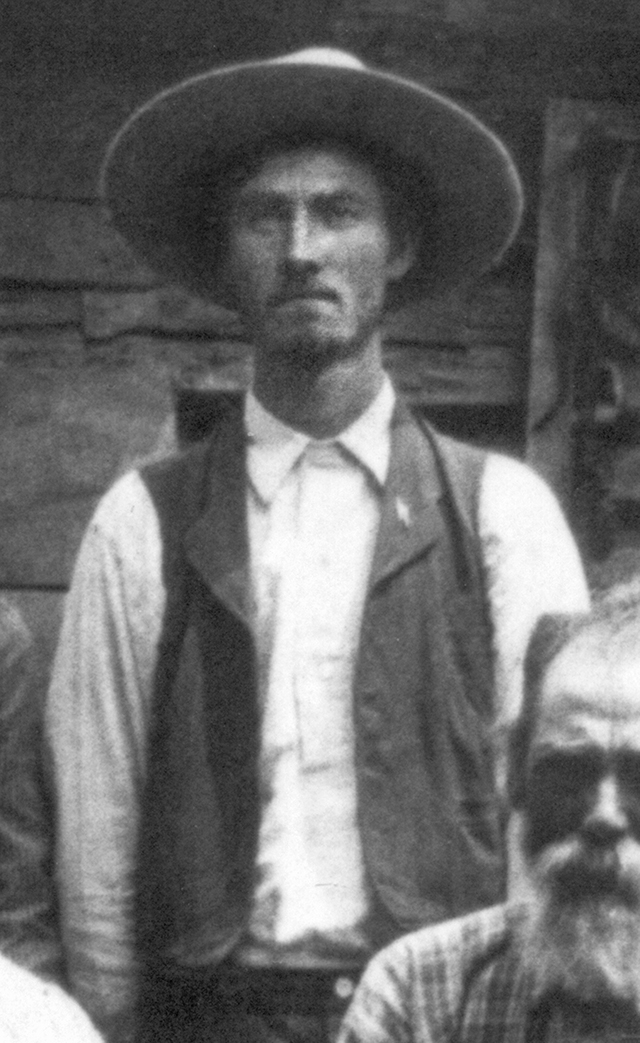

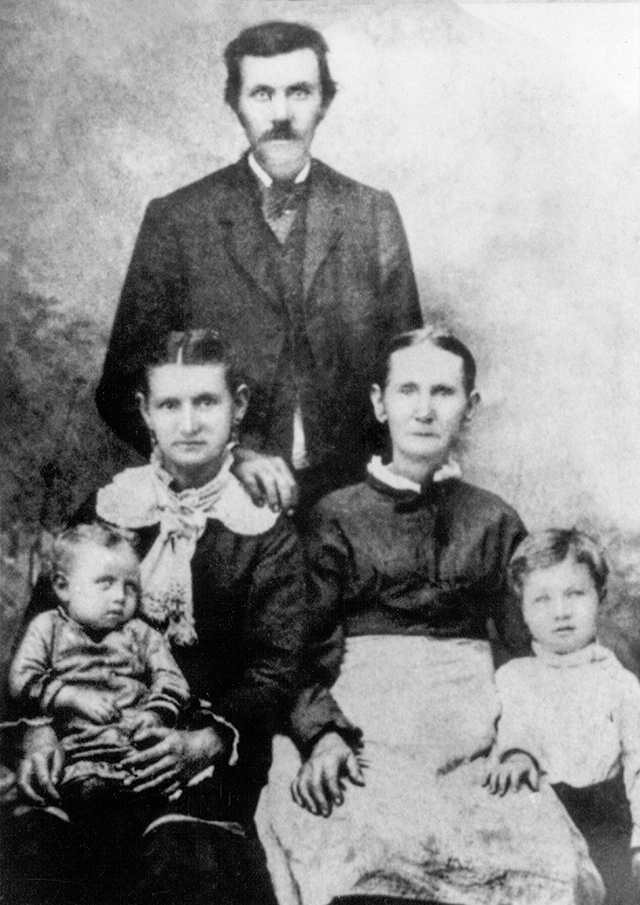

At 37, John James Thompson had already lived half his life by the time he found Indian Gardens in the mid-1870s, but he thought himself a younger man. Rail thin, with a wide forehead and a drawn face, Thompson never knew when he was born. Long after his death, his descendants located his baptismal records at the First Derry Presbyterian Church in Northern Ireland.

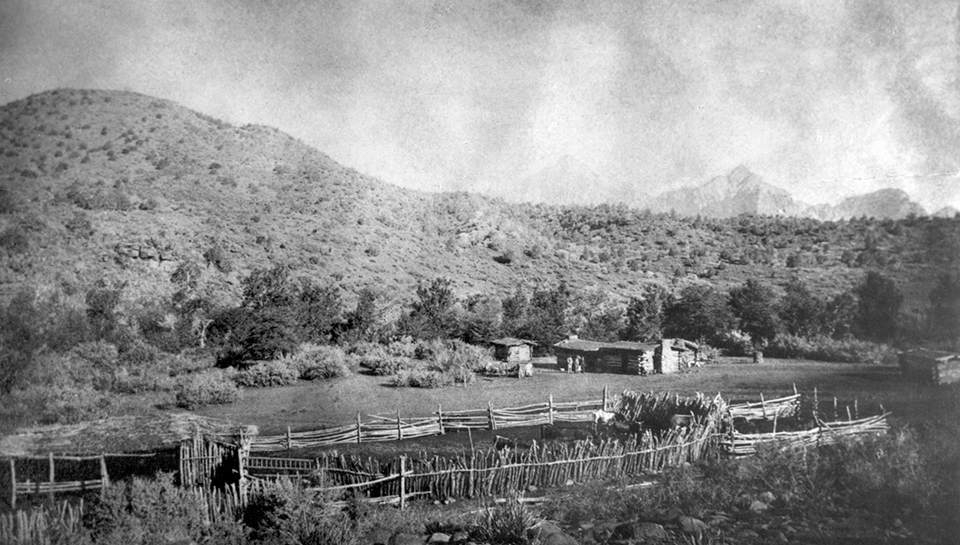

When Thompson first rode into the Indigenous camp, the U.S. Army had recently removed the so-called “renegades,” Apaches who had resisted relocation to San Carlos. They might have lived there undetected for years, Thompson thought, had they not been raiding livestock in the Verde Valley. He found their wickiups still standing and irrigation ditches watering corn, beans and squash. Taking a long drink from a spring, Thompson found it shockingly cold and decided to stay.

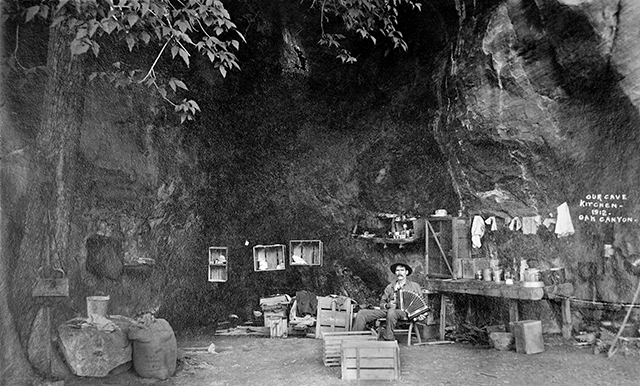

Posting a location notice on a tree, Thompson soon started building a log cabin. Meanwhile, seeing bear trails everywhere in the tall grass, he built scaffolding several feet off the ground to sleep on. Using a sapling as a rod and grasshoppers for bait, he could catch 40 pounds of trout in an afternoon to sell at Camp Verde. And, like any self-respecting Irishman, he planted potatoes. Thompson called his place Indian Gardens Ranch, later shortening it to Indian Gardens.

Born to strict Scots-Irish parents, Thompson sailed for New York when he was 11 — so young that the ticketing agent refused him a ticket. He got aboard only with the help of a young man he met on the docks. It was the second time he’d run away, chafing at his parents’ discipline and the drudgery of a printer’s apprenticeship.

From New York, Thompson’s initial goal was Canada. But, excited by tales of Indian fighting in Texas, he instead stowed away on a ship bound for Galveston. When he arrived, he met a childless couple with a ranch near the Irish enclave of Refugio, and they took him in.

With three other Johns in his new community, Thompson went by Jim, a name he’d use for the rest of his life. He never did fight Indians, but he learned to work cattle and to freight, which would eventually become his principal occupation.

Still seeking adventure, Thompson was itching to enlist in the Confederate Army when the Civil War broke out. But his enthusiasm soon dimmed: He was captured early on and sent to a prison camp. After his release, he was shot while fighting in Georgia. A surgeon told Thompson his right arm needed to be amputated or he would die. “All right,” Thompson replied. “I will die all in one piece.”

His arm eventually healed, but Thompson concluded the war was a big mistake and could have been avoided if not for hotheads on both sides. The Fourth of July became his favorite holiday — and, years later, an occasion for dayslong celebrations at Indian Gardens.

After the war, Thompson floated around, trying his hand at many things. He spent several years in Mexico before returning to the U.S., where he joined a long cattle drive and prospected on the Grand Canyon’s Diamond Creek. For a time, he operated a ferry across the Colorado River, where he met John Wesley Powell. He sold the operation to Daniel Bonelli, who gave his name to the landing that now is part of Lake Mead National Recreation Area.

After trying to sell wooden shingles in Phoenix — and discovering, to his dismay, that most of the adobe houses there had dirt roofs — Thompson went to Prescott and hauled timber before selling his freight outfit to explore Oak Creek Canyon. When he stumbled onto Indian Gardens, something about the place made him want to spend the rest of his life there.

But Thompson was a gregarious man. And, despite the place’s charms, he must have found it lonely. Perhaps thinking about the man’s daughters, he wrote to Abraham James.

Thompson had met James while operating the ferry and delivering mail. James and his wife, Elizabeth, had gone to California during the gold rush, but they hadn’t lasted long. Making their way back east, they’d stopped at St. Thomas, Nevada, to farm, hoping to build up their cattle herd and raise enough money to return to Missouri.

Thompson’s letter persuaded them otherwise. Sometime around 1878, the family moved to the Verde Valley, first farming at Page Springs. The following year, they moved to a place called Camp Garden, near the present-day Arabella Sedona hotel, where they put some land under cultivation and ran cattle, moving north to Munds Park with the herd each summer. Thompson spent a lot of time with the family and, in 1880, married Maggie James just after her 16th birthday.

Oak Creek Canyon was still wild and uninhabited, and Thompson was away a lot. Getting potatoes to market was difficult and there wasn’t much demand, so Thompson returned to freighting. For Maggie, he built a dwelling near the present-day Sedona Arts Center so she could be closer to her parents. When he was home, Thompson spent his days working at Indian Gardens and returned to Camp Garden in the evenings.

James didn’t live to see his first grandchild — he caught pneumonia and died the year after Maggie’s wedding. But before he did, he named many of Sedona’s formations, including Court House Rock (now Cathedral Rock), Bell Rock and Steamboat Rock.

Jim and Maggie welcomed their son Frank into the family in 1882. The first of nine surviving children, Frank was the first child born to homesteaders in the area. Their third child, Clara, was 3 months old when Thompson finally moved his family to Indian Gardens in 1887. “Frank had to take over the farming as soon as he was old enough, because Dad was gone from home so much,” Clara wrote years later. “Fred and I herded cows, pigs, ducks and chickens. We had to stay out all day and not even come in when we had company or to eat.”

When he went to market, Thompson bought 1,000 pounds of flour, a couple hundred pounds of sugar and coffee by the barrel. A later settler recalled that before a road was built through the canyon, residents transported supplies by wagon to the rim and brought them down on “Indian drags.”

“We made them by getting a couple of poles and nailing slats across them,” he wrote. “Then we would pile some stuff on them and … take off down the mountain. … We did not have much of a trail at first. It came right straight down the mountain over the tops of the brush.”

Around the time Thompson was getting married, a neighbor moved in up the canyon. Having recently escaped from jail, Jesse Jefferson Howard likely chose the spot on the West Fork of Oak Creek because it was remote and inaccessible. Assuming the name Charles Smith Howard, he built a small cabin and planted the area’s first fruit trees.

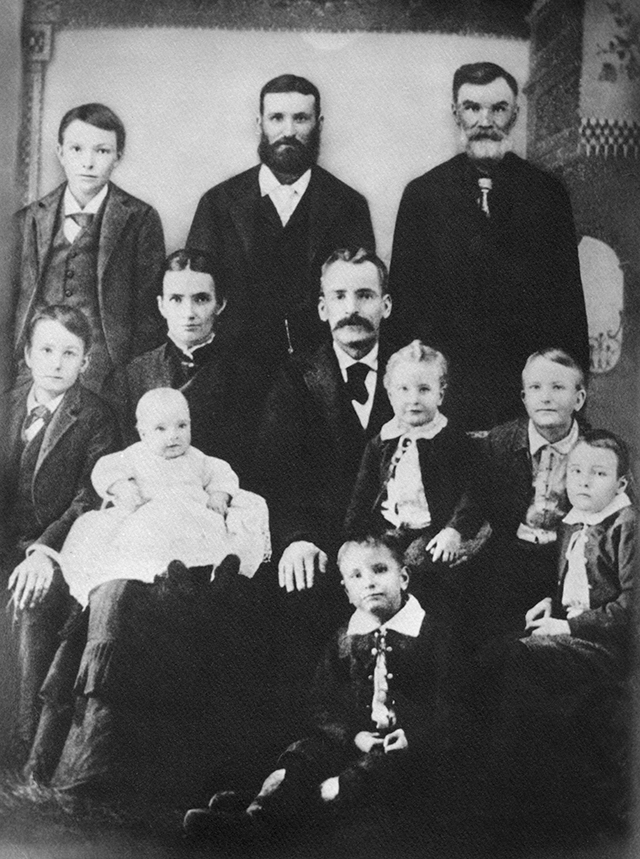

But Howard was not the type to blend in. To start, he stood at least 6-foot-4 — by some accounts, he was 6-foot-8 — and weighed at least 225 pounds. In photos, his bearded, heart-shaped face floats a full head above most of his companions. On horseback, he looked like he was sitting on a pony.

And Howard liked his whiskey. One bar patron reportedly required 29 stitches after tangling with Howard. But it was his skill as a hunter and trapper that earned Howard the greatest notoriety, as well as the nickname “Bear.” Already in his 60s by the time he arrived in Arizona, Howard hunted bear into his 80s. His exploits were so well known that he became a character in Western fiction, but his real-life exploits grew taller in the telling, too.

Born in Ohio, Howard fought in the Mexican-American War and was shot in Texas. According to a 1901 newspaper account, he carried that lead for more than 50 years until a Flagstaff doctor removed it that year, keeping the bullet to display.

After the war, Howard headed for California, where he made a living by hunting and trapping to supply prospectors. There, he married beautiful, dark-haired Nancy Cline, who had sailed with her parents from the Netherlands. Their first son died soon after birth, but Nancy gave birth to two more children, Jesse Jr. and Martha. She died when Martha was 3.

Bereaved, Howard sent his children to the mission in Santa Clara. After their return, Martha — along with Jesse Jr., in some accounts — was kidnapped by Indians until, with Howard in pursuit, her captors threw her into a cactus patch and fled.

Those were also the days of range wars, with sheep and cattle ranchers battling over grazing territory all over the West. Howard wasn’t a cattleman, but he did run horses and staked a claim near Ojai. After repeatedly finding sheep grazing on it, in 1877, he shot a shepherd.

Realizing he’d killed the man, Howard turned himself in. Convicted of second-degree murder, he escaped the night before his sentencing. Some said a sympathetic jailer set him loose. But a Ventura County deputy tracked Howard for nearly a year, locating him “in the mountain fastnesses of Arizona, then as wild a place as any in the world.”

A week after Howard returned to the Ventura County Jail, he escaped again. “The notorious Jeff. Howard … again escaped from jail,” a local paper trumpeted. A prisoner said Howard used a saw made from a table knife to cut the rivets from his shackles and the bolts that secured the lock. Howard then “offered to break open [the other prisoner’s] cell and release him, but he declined to go,” the paper reported.

Another account said Howard left behind “one crowbar, two knives, the shackles which had been welded in place around his ankles, and a fairly well destroyed jail cell.” And one newspaper bade farewell to Howard by saying, “We hope we never see you again,” adding, “We have to build a new jail.”

They never did see Howard again. At some point, he made his way back to the Arizona Territory along with Martha; her husband, Stephen Purtymun; and the first two of their nine children. To avoid putting them in danger, Howard traveled separately, joining their camp in the evenings. Sometime around 1880, he found the secluded spot near West Fork.

Bears were abundant, and hunting them was profitable. A hunter could earn as much as $50, the equivalent of more than $1,500 today, for the meat, hides and tallow. By 1897, ranchers offered a bounty of $110, while the government offered another $20. And Howard collected a lot of bounties: One year, he killed 12 bears by July.

Martha and her growing family moved around the Territory before settling in Northern Arizona to be closer to Howard, joining him in his tiny cabin for a short time. They established a homestead near present-day Kachina Village before building a cabin on Oak Creek in the late 1890s at the present-day site of Junipine Resort. Jesse Jr. came, too, and later proved up a homestead just below them at what now is Orchard Canyon on Oak Creek (formerly Garland’s Oak Creek Lodge and, before that, Todd’s Lodge).

Before there were enough children to warrant a school in Oak Creek Canyon, Maggie Thompson moved with her family to Red Rock, southwest of present-day Sedona, for a few months every fall. Henry Schuerman and his wife, Dorette, had built the area’s first school there when their oldest child turned 6.

“I went to the first school ever held there in 1891,” Clara recalled. “I was 5 years old. … It did not make any difference about my age, because I was needed to make up the attendance so they could have a school.”

Schuerman came to Red Rock in 1885 to check out land he owned but had never seen. He’d been living in Prescott, where his onetime employer, Dan Hatz, was experimenting with making wine from native canyon grapes. Hatz’s experiments may have interested Schuerman in making wine himself. If so, it may have seemed an attractive proposition when a couple who owed him $500 offered the deed to a farm at Red Rock to satisfy the debt. Schuerman accepted.

When he and his new wife arrived, though, it wasn’t at all what they’d expected. They thought the place wild and strange. They found only a small cabin on their property, no churches or schools nearby and not even any proper roads. They didn’t intend to stay. But the land was so remote, they couldn’t give it away. So, they rolled up their sleeves and made improvements in the hope of eventually selling the land.

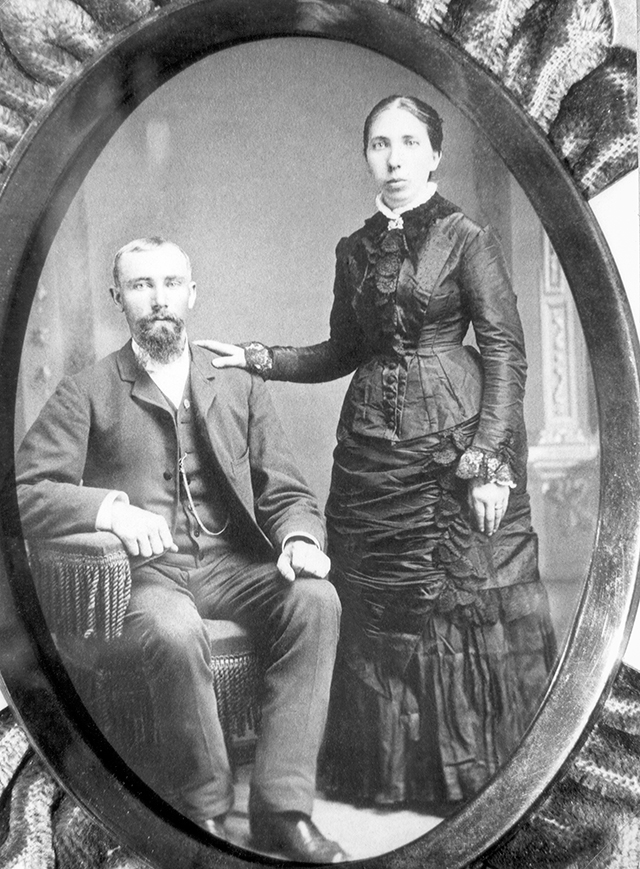

A German immigrant, Schuerman appears impeccably dressed in photos, with a neatly trimmed goatee, a jacket and a string tie. He served on the Red Rock school board for 25 years, and for years, teachers and sometimes students boarded at the Schuerman home.

Dorette wore bonnets and frowned on girls wearing pants. Her granddaughter, Martha Loy, recalls that she loved children, Christmas and books. Not knowing a word of English when she arrived at Red Rock, Dorette taught her children Scripture from a German Bible, finding translation too difficult. And she always spoke English with a heavy accent.

Jim Thompson’s grandson Paul remembers visiting the Schuermans when he was a child in the 1940s, and he recalls Dorette as a little wisp of a woman who always offered a glass of warm “mick” and a slice of fresh-baked bread with jelly.

Frank Thompson married a mail-order bride from east of London who spoke with a Cockney accent. Paul’s father, Albert, recalled that at the Schuermans’ 25th wedding anniversary celebration, Dorette observed, “Boy, Hilda sure don’t speak very good English.”

“My dad always got a kick out of that,” Paul says.

Born in the small mountain town of Melle, Germany, 17-year-old Johann Georg Heinrich Schuerman came to the United States with his friend Heinrich Beinke. Neither spoke English. Bakers by trade, the two traveled around the country, finding work in St. Louis and New Orleans, before heading West on foot. Years later, Beinke recalled walking “from Pueblo to Lake City, Colorado, both sleeping under one blanket that was hardly large enough for one.”

Beinke returned to St. Louis, but Schuerman, who Americanized his first name to Henry, arrived in Prescott sometime around 1877. Schuerman and his cousin, George, rented the Pioneer Hotel on Montezuma Street, changing the name to the Schuerman House after buying it from Hatz.

About the time Leonard and Minerva Carroll signed over their Red Rock farm, Schuerman began writing to his childhood friend Dorette back in Melle. “Dear friend Heinrich!” Dorette wrote back in an 1882 letter. “I wanted to write to you for a long time, but I never came around to do it. A little while ago you wrote that I should come over there. … Is the climate too warm and what are the other unpleasant points. … Write me about it then I shall think it over. … Do you think of youth memories once in a while. … Oh those were wonderful times. … Do you remember when we were together in your attic and you embraced me [and] I swooned.”

In 1884, Schuerman sent Dorette a picture, writing, “The house I am living in … is to the right of the courthouse. … My farm is not in the picture, in fact it is quite a distance.”

“It isn’t St. Louis yet today,” Schuerman said of Prescott, in response to Dorette’s observation that the houses looked small. “Twenty years ago there wasn’t a single house here in this area. My boss [Hatz] (a Swiss) was one of the first settlers here and had to be protected by the military at first.”

In June 1884, Schuerman met and married Dorette in New York City, and the newlyweds made their way back to Prescott. The following year, with Dorette expecting their first child, they sold their interest in the hotel and set out to find their farm. Making the best of their situation, they built a larger house and planted vegetables, an orchard and a large vineyard of mostly Italian Primitivo grapes.

By 1890, Schuerman had 20 acres of grapes under cultivation. Operating one of the Territory’s first commercial wineries, he was producing quality zinfandel under the Red Rock label and selling it to miners in Jerome. By the early 20th century, he was producing more than 35,000 pounds of grapes a year.

Dorette gave birth to Erwin in 1885. Elizabeth James, a midwife, delivered him, as she would all six Schuerman children. Their second child, Clara, died at age 4; the doctor chose a plot near their home, and Clara became the first person to be buried at Red Rock Cemetery.

Clara’s death was the first in a string of losses. In 1900, kids playing with matches burned down the Schuermans’ home. Dorette rescued her travel clothes and wedding dress, but nearly everything else was lost. Martha Loy says other family members have taken the blame, but she always understood Erwin was responsible.

The Schuermans rebuilt their home with stone, believing it would be safe. Then, the government surveyed their land and the Schuermans learned the Carrolls hadn’t had legal title to it. It belonged to the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad, and they had to buy it again.

A few years later, Schuerman filed on an adjacent 40 acres and built another small house on it. To meet the requirements of the Homestead Act, he and Dorette slept there every night for five years, returning to their stone house during the day.

On January 1, 1915, four years before Congress passed the National Prohibition Act, Arizona went dry. It’s unclear whether Schuerman understood he was breaking the law or thought there was no harm in selling his existing inventory. But in May 1917, he sold 100 gallons of wine for $80. After the buyers picked up two 50-gallon barrels at Red Rock, police stopped and arrested them on their way to Clarkdale.

After pleading guilty, Schuerman was sentenced to six months in jail and a $300 fine. Friends petitioned for his release, gathering hundreds of signatures and exerting whatever political influence they had.

It was a dark time for the Schuermans. After the country entered World War I, their sons Fritz and Henry were drafted and sent to France. As registrar for the Red Rock precinct, Schuerman had signed their draft registrations.

In October, Dorette wrote to her husband: “Every day we are waiting for you but you are not here yet. The boys are gone. Yes, this was the more horrible day in my life.”

Schuerman’s cousin George died the following month. In a letter to his daughter Frieda, Schuerman wrote: “Yesterday we buried George H. Schuerman. Mama and me were in the second car behind the hearse. … The way it looks now I will be out of here by the 15th of Nov. Mr. Fredericks and Mr. Goldwater [the future senator’s father] went to Phoenix and Tucson last week and I think they will fix things for me.”

In December, Governor Thomas Campbell pardoned Schuerman, citing his “exemplary conduct and good citizenship” throughout his 40 years in Arizona. It added that with two sons away, Schuerman’s property had suffered and confinement was affecting his health.

Schuerman returned home but never recovered. “They think he was depressed after all that,” Loy says. Then, after a 1919 flood, the Schuermans had to rebuild their home for the third time. Schuerman died the following year, at age 68. “For the last year Mr. Schuerman has been failing and his family and friends have known for some time the end must come,” a local paper reported.

Dorette buried her husband at Cottonwood Cemetery. Red Rock was too close, and she didn’t want to be reminded of her loss every day. As market conditions changed, orchards eventually replaced most of the vineyard.

One of the students who attended the Red Rock school was Ambrosio Chavez. His father, Manuel, brought his family to Red Rock not long after the Armijo family settled near the Schuermans in the early 1890s.

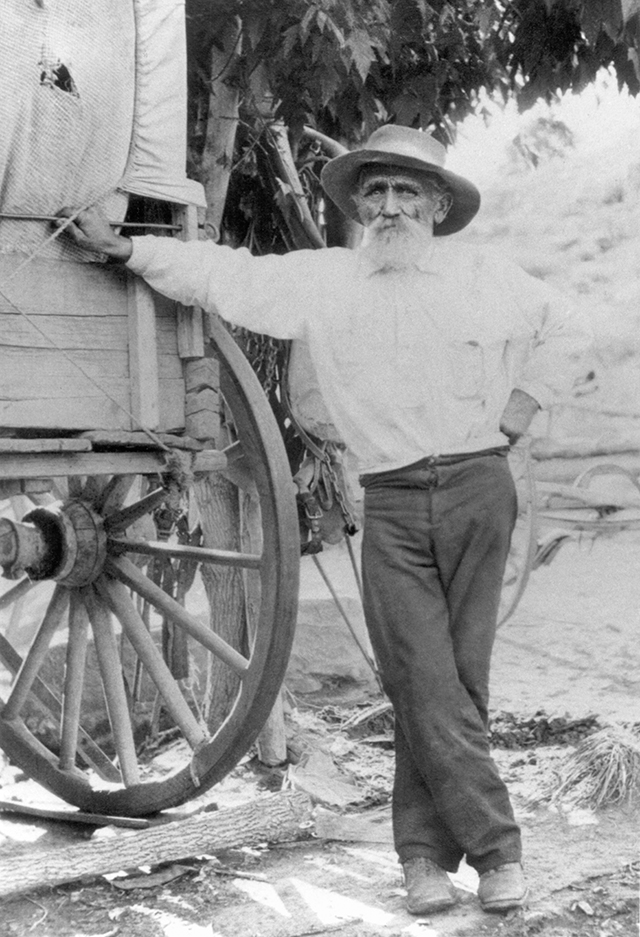

Manuel grew up in Santa Fe, New Mexico Territory, and joined the Army in 1862, serving as a scout and guide in the Apache Wars. A thin, wiry man with a full white beard, Manuel would have to fight the government to get his pension, riding alone on horseback from Red Rock to St. Johns to hire a lawyer while in his 70s.

The Chavez and Armijo families had long been close. Both families came to Arizona from New Mexico, where they had deep roots. In Arizona, both families had lived in Flagstaff and in the Hispanic community of San Juan, which English speakers later Americanized to St. Johns.

And both families had a lasting impact on the Red Rock district, patenting five homesteads between them. Along with Schuerman, Juan Armijo and Manuel both served on the Yavapai County Board of Supervisors. Armijo also served as justice of the peace and, in that capacity, officiated at Clara Thompson’s wedding. After he left the area, Armijo appeared in the inaugural Who’s Who in Arizona while serving as chairman of the Apache County Board of Supervisors in 1913.

But it was Manuel’s son-in-law, Juan Nuanez, who brought the Chavez family to Red Rock. Nuanez tried to file on a homestead near the Armijos, but a question about his citizenship prevented it. So, Manuel moved there with his wife, Inezita, 2-year-old Ambrosio and the rest of their family, then filed on Nuanez’s behalf.

When Manuel had proved up the homestead, he gave it to Nuanez and moved up the creek, trading Abraham James’ son Dave an old wagon and a set of harnesses for the rights to land on which Dave was squatting. Because Manuel had used up his homestead rights, Ambrosio filed on the property when he came of age. And when his citizenship issues were cleared up, Nuanez homesteaded an adjacent parcel in his own name.

The Chavez family ran cattle and planted alfalfa, orchards and a large truck garden. In his final years, after losing his sight, Manuel moved to Flagstaff to be near his son Andrew. A few years after his father died, Ambrosio married a woman he’d met at a J.C. Penney store in Winslow. It’s said that he announced he would take out the girl who would buy a box of peaches from him. Apparently, Apolonia Peralta liked peaches. And apparently, she also liked Ambrosio.

Ambrosio brought his bride to Chavez Ranch, where they built a home of native stone nestled among willows and cottonwoods, with vine-covered walkways leading to alcoves with statues of Catholic saints. Within a few years, Apolonia gave birth to Ambrosio Jr. and Dora. And when Nuanez was killed in a mining accident and his wife died a year later, they adopted 8-year-old Al.

Irene Rodriquez Brown wrote about summers she spent at Chavez Ranch with her cousins. “One of the first chores of the day for Uncle Ambrose and Lotatio [Al] was to milk the cows and feed the animals,” she recalled. “They would bring the milk to the house, wash themselves and get ready to eat breakfast. If Dad was there, Uncle and Dad would have a shot of whiskey. … [Dad] told me it helped digestion.” During Lent one year, Brown remembered, Apolonia asked Ambrosio if he could give up swearing. “Hell, yes,” he replied.

“We did a lot of hoeing of the weeds,” Brown wrote. “I can still see Uncle and Lotatio carrying shovels to divert the water to irrigate all the crops and trees. … In the fall, we would help Uncle pack the fruit and vegetables so he could take it into town. Green chile was a good seller.”

Life on the ranch had changed little by the time Al’s son, Frank, started working with his adopted grandpa when he was 8 or 9 years old. “[Ambrosio] could cuss in two languages, and he was hardcore,” Frank says. “But I loved the guy. He was amazing. He was up at the crack of dawn, and one of his favorite phrases was ‘We’re burning daylight.’ We’d be there weeding when the sun’s coming up.” And in an age when farmers were using tractors, Mollie and Brownie provided the horsepower on the ranch. “We used those horses every day,” Frank says.

One day, while Ambrosio was driving an old truck up Schnebly Hill to sell produce, Frank recalls “the wheel and the axle and brake drum came off and [were] running beside us.” Without missing a beat, Ambrosio stopped, “got the axle, jacked up the truck and slammed it in there. We went on into Flagstaff and went home.”

The last time Frank worked for his grandfather, Ambrosio was well into his 80s. “He worked me to death,” Frank recalls. “But I’m glad he did, because he taught me how to work.”

Today, the names of those early pioneers are inscribed on the landscape at places such as Thompson Point, James Canyon, Schuerman Mountain and Chavez Crossing.

After Bear Howard left Oak Creek Canyon, his cabin was incorporated into Mayhew Lodge, which burned down in 1980. But a few remnants of the lodge remain along the West Fork Oak Creek Trail, as do some trees Howard may have planted. Once named for him, the A.B. Young Trail was built along a path Howard used.

Much of the Armijos’ land became part of Red Rock State Park, and Chavez Crossing is now a U.S. Forest Service campground.

Martha Loy, who grew up in her grandparents’ second homestead house, donated it to the Sedona Heritage Museum. And several years ago, Eric Glomski of Page Springs Cellars began planting cuttings cloned from one of Schuerman’s original vines. He used fruit from them to produce a small batch of zinfandel, donating most of it to be auctioned to support the home’s restoration.

Primitivo grapes generally don’t grow well in Arizona. But the vines cloned from Schuerman’s produce fruit with characteristics better suited to the state’s climate. “I think there’s great potential for this clone,” Glomski says, “which we clearly have to name the Schuerman clone.”

So, in the same way these places honor the memory of the pioneers who settled there, a new generation of vintners may also carry Henry Schuerman’s winemaking legacy into the future.

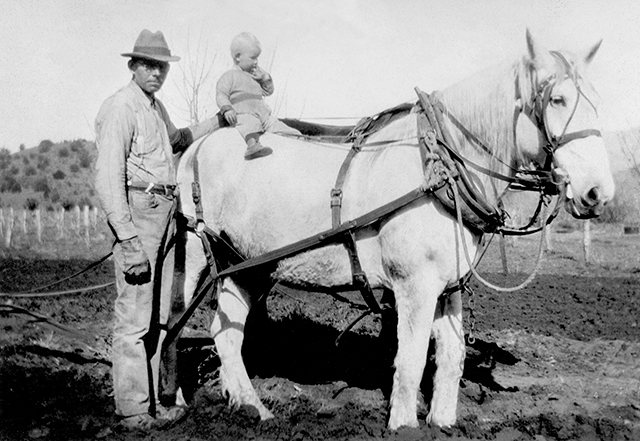

Thompson And James Families

Early settlers of the Sedona area

Howard and Purtymun families

A legendary hunter, a checkered past

Schuerman Family

From life in Germany to a winery in Arizona

in an undated photo.

CHAVEZ FAMILY

A lasting impact on Red Rock Country