He came to Arizona in 1909, fresh from Yale University, where he'd earned a degree from the first forestry school in the United States. Like many young college graduates, Aldo Leopold expected to leave his mark on the world. And he did. Through his experiences and writings, Leopold became a leading voice against America's indifference to ecology.

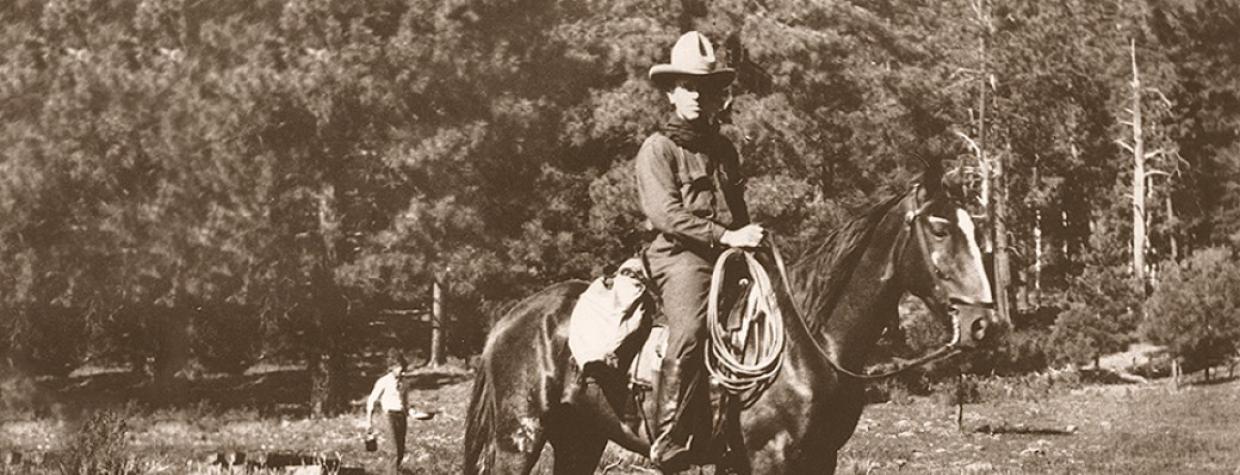

Enthusiastic, energetic and, perhaps somewhat naïve in the ways of the West, Leopold traveled by train from Iowa across the Great Plains to the soaring landscapes of the Southwest to work for the newly formed Forest Service. His first assignment — as a forest assistant for the 1-year-old Apache National Forest — brought him to the Arizona Territory. For the next two years, Leopold explored Arizona's White Mountains and fell in love with "the Apache." It was there that his views of wildlife and land conservation began to take shape.

Over the next decade, he moved up the ranks in the Forest Service, becoming supervisor of New Mexico's Carson National Forest. He was only 24. Eventually, the conservationist left the Southwest and moved back to his native Midwest, where he chaired the country's first Department of Game Management at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. He'd spend the rest of his life in Wisconsin, but he never forgot his time in Arizona.

In the course of his life, Leopold wrote more than 500 works, but he's best known for A Sand County Almanac, a collection of 41 essays that describe his Wisconsin home and outline his ideas about land ethics. In one of his most popular essays, Thinking Like a Mountain, Leopold wrote about killing a wolf in the Southwest:

"We reached the old wolf in time to watch a fierce green fire dying in her eyes. I thought that because fewer wolves meant more deer, that no wolves would mean hunters' paradise. But after seeing the green fire die, I sensed that neither the wolf nor the mountain agreed with such a view."

Leopold recognized that killing the wolf had serious implications on the mountain's ecosystem. So, he wrote about the effects, as well as other ecological issues. Although he died of a heart attack in 1948 — while helping his neighbors fight a grass fire — his writings helped initiate the modern environmental movement, and today he's regarded as the father of wildlife conservation in America.