FOR MOST OF MY YOUNG LIFE, I’ve traveled U.S. Route 160 to my family homestead in Teec Nos Pos more times than I can count. I pass the usual landmarks: the steep, winding road that leads to a place the locals call Red Wash; a wild Christmas tree someone always manages to decorate every holiday season; and the state line, where Arizona and New Mexico meet.

No matter when I make the drive to my late grandmother’s home on the Navajo Nation, I always manage to come across a herd of horses or a straggling mare. Up until last year, I never thought much about the horses that take the reservation as their own and roam free.

It wasn’t until recently that I began to wonder about horses and my family’s connection to them. I like to think the recent thoughts stem from a visit my parents, my uncle and I took to a place called Yellow Rock Point, Utah, which once was home to our family’s winter sheep camp. The place is named after a pointed rock that looks like the tip of an ice cream cone.

On that visit, which was around this time last year, my mother told me a story about an experience she had with her late grandfather Kady — as he was known to most — and his many horses.

It was a summer morning when Kady asked my mother to bring in a straggling horse. She looked high and low, but it was nowhere to be found. Feeling hopeless and afraid, she started to cry and continued looking. Then, at a distance, she saw two pointed ears peeking out near Yellow Rock Point. It was the horse she was looking for, a reddish-brown mare. She walked up to it, asking it, “Háadishá’ nánínáánit’éé’ ” (“Where were you?”), untied the rope used to hold the front hooves together and threw it around its neck to use as a makeshift rein. She had been taught to properly mount a horse, but, feeling defeated and defiant, she led the horse to a nearby rock and used it to hop on.

The story is one I’ve heard often, and for the past year, I could not get it out of my head. Why was this memory so important to her? Exactly who was this great-grandfather of mine they called Kady? And what made him the expert horseman everyone said he was?

AT THE START OF WINTER, I hopped back onto U.S. 160 looking for answers to all of my questions and more. I turned to my grandmother’s surviving brothers and sister for answers — and got more than I had bargained for.

I learned my great-grandfather Kady, who was more formally known by his children as Hastiin Gonna Yéé Biye’ Kady Wolyéhígíí, was descended from Hastiin Gonna, a man named after the fact that he was missing part of his left arm. Hastiin Gonna endured the Navajo Long Walk in the mid-1800s and shared stories of that devastating event, which changed the Diné’s lives forever. He said Navajo women spoke of how horses endured the Long Walk with the people.

And most of his children lived to share the stories. My grandmother Mary Kady Clah was the eldest daughter to Kady and the second-eldest of her siblings. George Kady was the eldest, then Mary, followed by Clifford Kady, Leonard Kady, Willie Kady, Paul Kady and Marilyn Kady.

“We took a whole bunch of horses over there [during the Long Walk], and not even one horse turned around and came back — we came back with the horses four years later,” said Leonard, recalling stories from Hastiin Gonna. “The horses never left us … they didn’t take off from us. That’s why the horse is so important.”

The stories of Navajo people and horses during the Long Walk laid the foundation for Kady’s admiration and respect for horses. And even before the Long Walk, it was known among the Diné that horses and other animals came before the people. Horses were said to have been given to us as a gift from the Holy People.

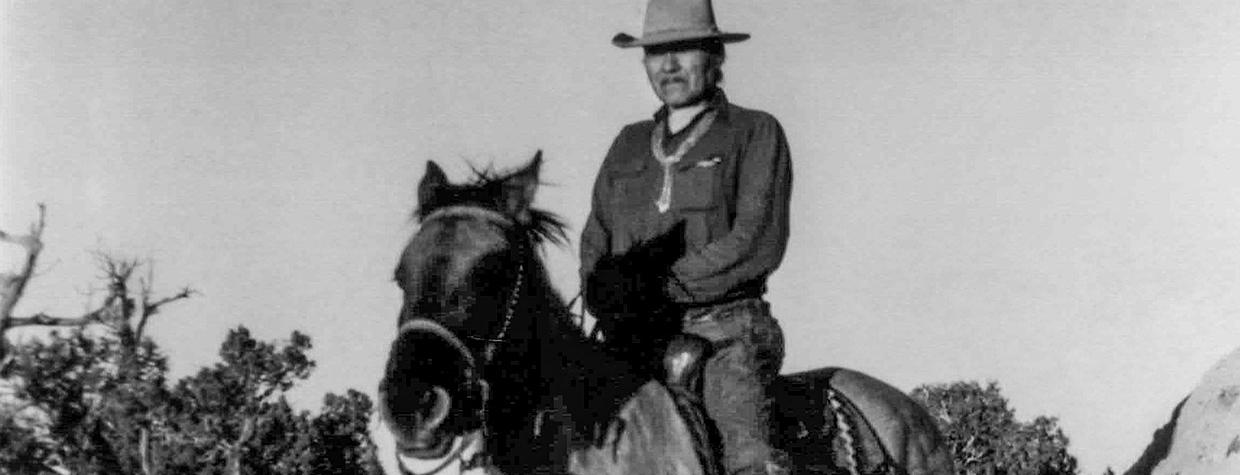

Kady was born near Yellow Rock Point and was of the Bit’ahnii clan. He grew up traditionally and developed his skills as a horseman early in life. As he matured, he was known for his physical strength, his horsemanship and the hundreds of horses he owned.

It is said that when Kady was about 18 or 19, he was out herding sheep and horses between the homestead in Yellow Rock Point and Aneth, Utah, when he saw two horses at a distance, standing nose to nose on the horizon. He inched closer to see if the horses were real. As he got closer, he could see that they were. They also were identical: pitch black, with the exact same conformations.

Horses were said to have been given to us

as a gift from the Holy People.

Kady realized the horses were on the other side of a small wash, atop a small hill. He made his way down the wash and up to the other side, but when he got there, the horses had disappeared. The land was flat and stretched for miles, so he knew they couldn’t have bolted off in any direction. Confused, he returned home to tell the family about the horses he had seen. The following day, he and some of the family members returned and looked high and low, but they saw only tracks that led nowhere. However, Kady did find two small horses made of steel, facing each other the exact way he remembered seeing them from afar. He and the family took the horses home and kept them in a safe place.

About a year later, a colt was born, and it looked exactly like the horses Kady had seen the year before. The following year, another was born with the same conformations as the first — and it was pitch black, exactly the same as the first. The vision of the two horses Kady experienced was said to have been a message, perhaps telling him that he would later have horses, and many of them. The small steel horses were left for him — a gift, if you will — and as long as he kept them, he would have many horses. And he did.

“In those days, in Navajo culture, people believed in it,” Leonard said. “But these days, nobody does. They brought them back; they had songs for them. The [horses] have their own ceremonies.”

The two horses became Kady’s prize horses. The three became a team that helped the family and the community survive the years to come. Eventually, Kady had hundreds of horses, but he used the two black ones for everything. He helped build dams in the Four Corners area under a New Deal program, receiving a dollar a day for his work. He helped establish an irrigation system from the Carrizo Mountains, south of U.S. 160. Later, he and his horses pulled his wagon and plowed the family fields and those of community members. He also helped others haul wood, groceries and whatever else they needed hauled. He was one of the first Navajos to run a freight wagon service, hauling flour from Farmington, New Mexico, through Teec Nos Pos to Kayenta, Arizona, along U.S. 160.

“He slept in the wagon every night. He just had one team, those two black horses. … Everyone else had two teams of horses,” Willie said. “Those two black horses never got tired. He always admired and cherished the two black horses that he had.”

All of his horses worked for him. He trained them with respect, and in return, they worked hard. Kady believed horses were a lot like the Diné: They were hard workers, partners, colleagues. And in return for their hard work, they received shelter, food, respect and companionship.

WHEN KADY HAD CHILDREN, including my grandmother, he passed his horsemanship down to them. Leonard recalled when he and two of his brothers were in a horse corral at one of their winter sheep camps, trying to rope a newly acquired wild horse. The horse was afraid and started kicking. Kady saw them from the top of a hill and yelled at the boys, asking what they were doing and saying that was no way to rope a horse. He came down to the corral, snatched the rope away, walked to the horse and gently placed the rope around its neck. Leonard said the horse looked backed at them and let out a deep neigh.

“The horse knew his voice — he recognized the whole thing, what was happening,” Leonard recalled. “These horses have memories for a long time. They can recognize you from a distance if it’s your horse. He can hear your voice; he knows.”

My great-grandfather understood horses. He had the magical touch that horses respond to. He knew how to approach them, how to earn their trust and how to treat them. He often sang to the horses and blessed them with corn pollen in an effort to protect them. When he acquired a new horse, he’d sing a special song to it while tying it to a post; the song was sung to keep the horse from running away and returning to its previous home. And when he shoed his horses, it took little to no effort, because they knew and trusted him. The horse would gently lift its hoof, and he’d gently place it between his knees and put the shoe on.

“A lot of people didn’t know how to do that, so some paid him a dollar to put horseshoes on,” Leonard said.

He was the most sought-after horseman in the area. Many looked to him, and later to his sons, to catch wild horses for them. George, Kady’s eldest son, took after his father when it came to his love and appreciation for horses. Like his father, he had a way with horses and was often sent on behalf of his father to catch wild horses for those seeking horses of their own.

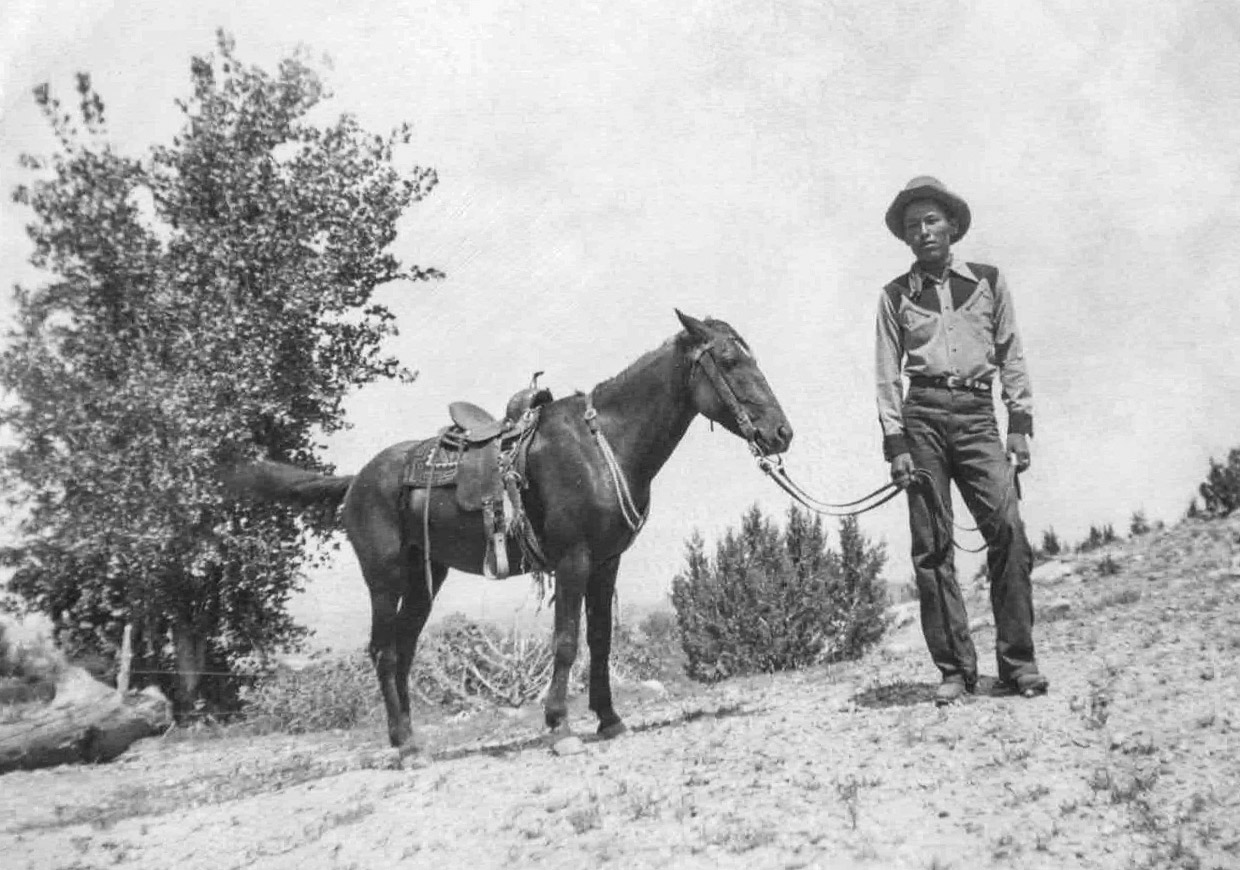

During the Navajo Livestock Reduction, starting in the 1930s, thousands of cattle, horses and sheep were rounded up and slaughtered by the United States government in an effort to protect areas that were thought to be overgrazed. Knowing officials were rounding up livestock, George used the winter sheep camp, which sat in a box canyon, to hide some of the family’s best horses. During the day, he’d corral them in a cave-like enclosure that sat in the canyon; at night, under the cover of darkness, he’d take them to the San Juan River to drink and graze. Before the sun rose the next day, he’d take them back into hiding and repeat the process. George knew how important the horses were to the family, to their upbringing and to their survival. He tirelessly looked after the sets of horses that would later breed to create another large herd like the one his father had owned.

The Kady children all grew up with livestock. Every family member had a horse they called their own. Men and women alike had horses, and the men trained all of their horses with their father’s guidance. It was from Kady that they also learned about the relationship between a horse and its owner, and the spirituality that runs deep within a horse.

Kady taught his children that horses develop deep relationships with their owners. One time, Kady and a friend roped the horse Willie would call his own. It turned out to be a horse that liked to run and almost never stopped. It was said the horse turned out that way because when he was roped and blessed by his father’s friend who helped rope him, they cut four slits of a leather whip and proclaimed that the horse would never have a whip used on him.

“I never used a whip; you always had to hold him back,” Willie said. “[When] you let the reins fall or when you let it loose, it started walking fast, starts trotting, he takes off. When you own a horse and use him most of the time, both of you will acquire each other’s attitude. They adopt your habits and all that. That’s what my dad used to tell us.”

Willie said it’s hard to deny his father’s teachings about horses. He said Kady often lectured his children about treating their horses with the utmost care and trusting them. But Willie learned the hard way. He and Kady once rode their horses to the trading post from the summer sheep camp atop the Carrizo Mountains. They spent the entire day at the store and started to make the trek back as the sun began to set. Willie grew nervous because he realized they were losing daylight and there was no moon in sight. He asked his father why they were waiting, and his father told him, “Horses have a quality of things that humans don’t have. He has the ability to sense danger from here to the highway. If there’s something beyond that hill, if there’s danger, the horse will tell you.” He also told Willie they were waiting because the rocks needed to cool so they would not affect the horses’ hooves.

The way you treat them, they’ll be the same way

to you,” Willie said. “They’ll take you wherever you want

to go, but you have to take care of them.”

When the two finally made their way onto the horse trail to the sheep camp, it was pitch black. Kady told Willie to let go of the reins and let them hang, saying the horse knew exactly where to step. “I had nothing else to do but sit there and trust the horse,” Willie said. “If we were walking [without horses], we would easily walk off a canyon, but the horses, they knew. They knew exactly where to go, where the road is. They can see in the dark. They can sense things.”

Kady believed horses were sacred. Every part of the horse’s body had a special purpose and representation. It was taboo to cut the mane or tail, as they represented the rain and cutting either of them would bring on a drought. It was said the horses should not be covered in blankets, as it interfered with their ability to adapt to natural elements. An arrowhead often was placed under each hoof with the tip facing forward, so the horse understood where it needed to go. Horses also played a vital part in Navajo ceremonies.

“The way you treat them, they’ll be the same way to you,” Willie said. “They’ll take you wherever you want to go, but you have to take care of them. If you mistreat them, then they start working against you. They repay you.”

I JUMPED BACK ON U.S. 160 and headed east. Before my sit-down with my grandmother’s siblings, I hadn’t thought much about my connection to horses beyond the stories my mother told me. I’d been on the back of a horse a few times in my lifetime, not knowing the strong connection my family had with horses.

But as I made my way home on U.S. 160, I took note of the wild horses that roamed the flat stretch of land and wondered if they, like me, were descendants of a great horseman they called Kady.

Sunnie R. Clahchischiligi is an award-winning journalist and writer whose work has appeared in The New York Times, Rolling Stone and other publications. A fifth-generation Navajo rug weaver, she also is an instructor and Ph.D. candidate at the University of New Mexico. This is her first contribution to Arizona Highways.