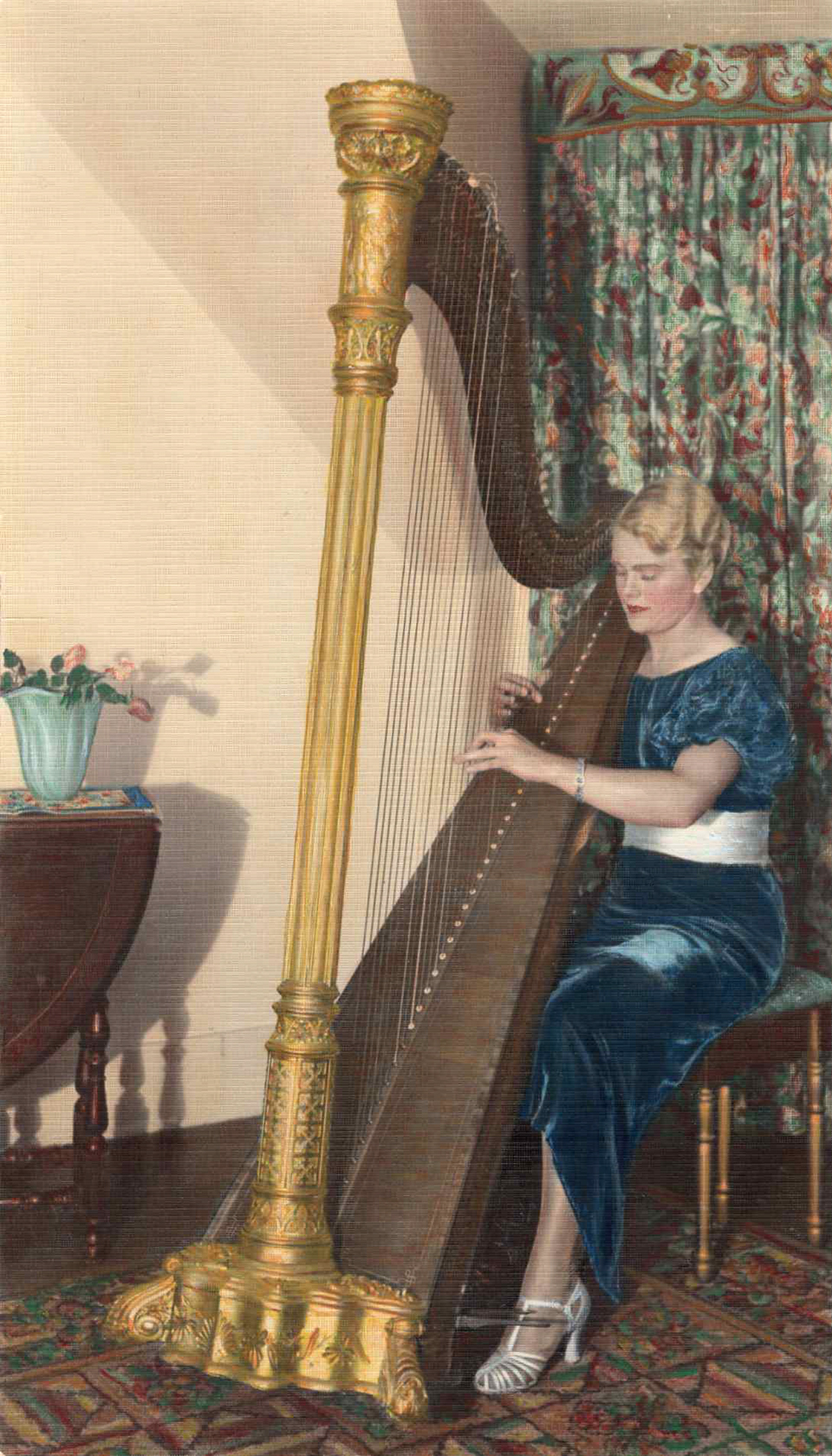

Joyce Rockwood Muench

Writer

1907–1982

One cloudy day in 1954, Joyce Rockwood Muench was dusting bookshelves when a single ray of sun fell directly onto the spine of Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales. Understanding it as a sign, she pulled the book from the shelf, opened it and read, “Whan that Aprille with his shoures soote ... .”

Chaucer had invited her on a journey into spring.

Her article, Pilgrimage Into Spring, was published in Arizona Highways in February 1955, then reprinted in the March 2018 issue. Reading her piece in preparation for my own article about spring for that issue, I was awed by the erudition I ascribe to anyone who reads Chaucer. (I never get very far.) I did, though, note that we shared the sense of adventure any journey into spring implies — a journey into the start of things.

We also share the last name of our photographer husbands. She is the mother-in-law I never met; I think we would have been friends. In 2018, Editor Robert Stieve liked the idea of including us both in the same issue.

Growing up in Two Rivers, Wisconsin, as the daughter of a college professor and the middle child of three, Joyce charted her own particular route through life. When her father accepted a job at the University of California, Berkeley, the journals she had already kept for years acknowledged her sadness at leaving close friends in Two Rivers but brimmed with excitement at spending her last two years of high school in Berkeley.

Like most literary teenagers, Joyce wrote poetry — poetry of longing, of exploration, of the search for meaning. Reading a notebook filled with her teenage poems, I was as moved by the intensity of feeling expressed in them as I was by the freedom in her writing to voice those feelings.

The notebook of poems was one of many packed in a box of Joyce’s journals, articles and unpublished stories. In another box, I found somewhat later writings, stories (labeled with the prizes they had won), typed copies of her journal entries, and tear sheets of articles written for Arizona Highways and other publications.

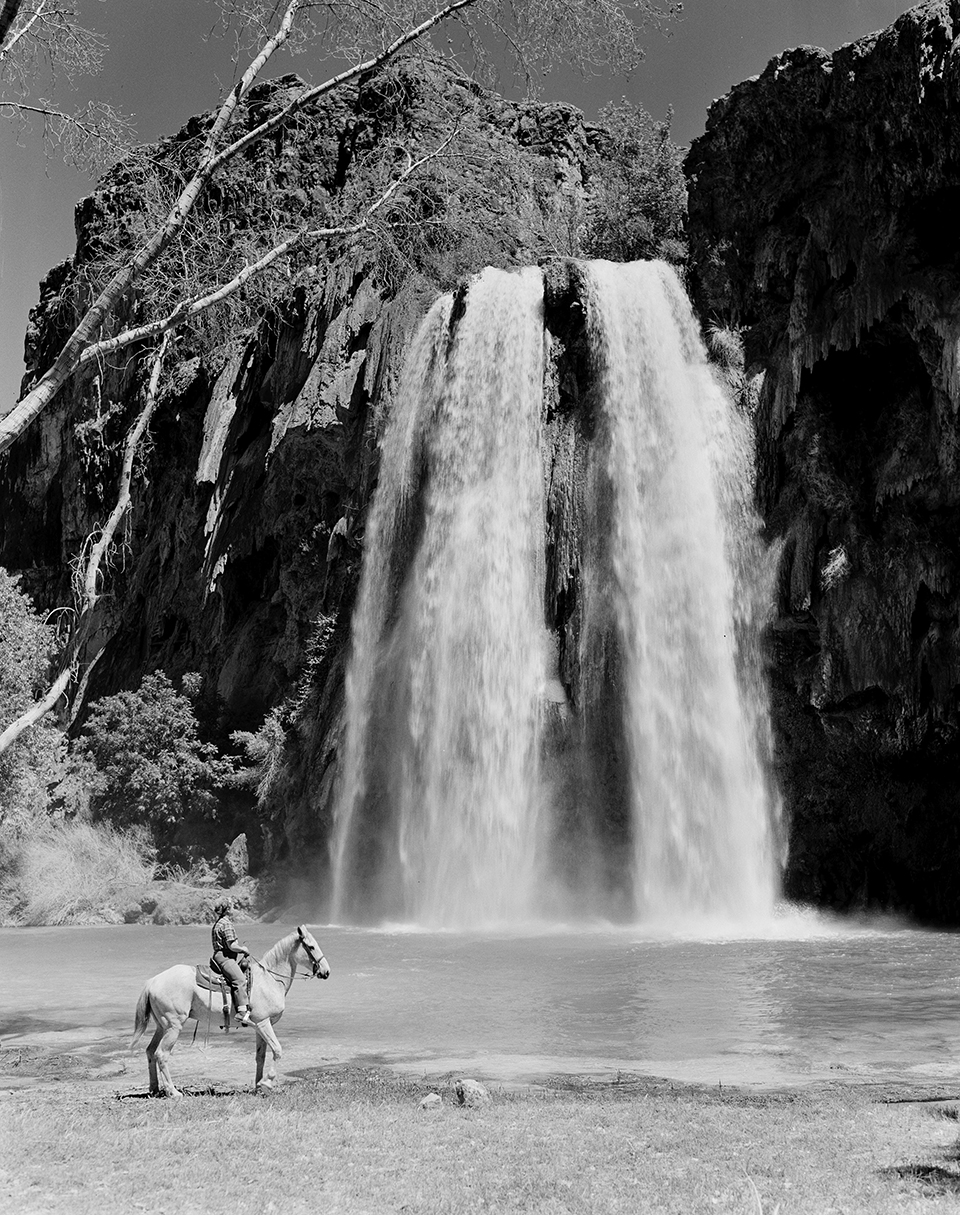

Most of her published writing was bylined Joyce Rockwood Muench, but she was a writer, if unpublished, long before she met Josef Muench. An experienced equestrienne, she and Josef met on horseback in a place called Happy Valley, California. (I’ve recently discovered this was an organized ride, although I prefer the version I’d imagined, in which the two of them, each alone on a horse loping across vast meadows from opposite directions, stop to chat. Finding they both are artists enamored with nature, they marry and go on to work together.)

I know nothing about their courtship. Nor does David, their son, which is probably as it should be. Although Joyce wrote pages and pages about a college love, I found only two journal entries connected to the relationship between Joyce and Josef. While she was in the hospital, producing her only child, she wrote, “I didn’t think it would be so hard to give birth.” This woman, imaginative and attentive to everything, had apparently not considered the reality of childbirth. (She did, however, have her journal with her.) A few days later, she wrote, “I love watching Joe hold the baby.”

Joyce was almost as excited about a new notebook in which to write as she was about the writing itself. “I like this journal so much!” she wrote. “As soon as Dad pulled it out of the box it looked interesting, and when he said I might have it, I knew it was to be my journal. I have a number of short stories I want to put into volumes. I have written some new sketches, and there are several that are waiting impatiently to be written.”

I understand the excitement of a new blank book — the anticipation of all that will go into it, the physical movement of a pen across the page, the reality of writing. Joyce’s image of herself was always that of a writer.

Which, on some level, makes it curious that at Berkeley, she majored in physical education. There is no one to ask how she became a gym teacher, although with Title IX, the landmark gender equity legislation, far in the future, it was one of the professions open to athletic women. Joyce was involved in her high school and college newspapers, too, and she continued to enter her stories in contests and record hopes and ambitions in her journals. But she never expressed a wish to major in literature or writing. She quotes from a letter written to her by “dear C.E.K.,” possibly a teacher: “I never wanted to dissuade you but wanted you to realize that there were two sides to majoring in Phys. Ed. … There is true joy in this field and not the smallest joy in being able to know and play with the girls. ... Please don’t get too highbrow ... it would be sad not to be able to converse with you. ... You must remember that Phys. Ed. did crowd out a lot of Thackery and Aristotle ... so keep a little bit of ordinary stock of conversation and thought around, won’t you?”

Joyce’s athleticism was useful when she and Josef began exploring the Sierra Nevada on pack trips. According to David — who was pulled out of school to go along but was required to write reports about the trips — they led donkeys and mules carrying their gear. Steep and rocky, the Sierras are terrain for serious hikers and adept riders. Kings Canyon, a favorite area for Joyce and Josef, requires skill and attention, both natural to Joyce. When Editor Raymond Carlson sent Joyce to Chiricahua National Monument for an Arizona Highways story, he called her “one of our most adventurous writers.”

Wanting her stories “out there,” Joyce entered them in writing contests, winning two first prizes, a second place and a couple of honorable mentions. She had bound a collection of stories on typewritten pages. It’s titled Prose, her name is printed under the title, and it includes work from 1922 to 1930. King’s Play, written in 1928, was awarded first prize — a book and $5 — in a 1934 contest. Another story, The Kut Sang, won first prize in a short story contest conducted by the literary society at Washington High School in Two Rivers in 1922, when she was a freshman. The award was $2.50.

The first page of this bound volume reads: “Collected in Santa Barbara, Calif., in the spring of 1936 from over a period of years and arranged more or less in the order written.” The spring of 1936 is close to the birth of Joyce’s only child, so it seems a natural time to be thinking of the work she had already produced.

Joyce was in her 50s when she left her marriage and moved to Arizona. In 1970 she wrote the editor of Arizona Magazine, a publication of The Arizona Republic, suggesting an article on dog training. College for Canines was, in fact, an idea close to the heart of this dog lover, but what strikes me is Joyce saying she hoped her name would ring a bell with the editor — that he had used work of hers when she was “the writing part of the Josef and Joyce Muench team.”

“I am now using my maiden name,” she continued, “and doing my own photography. I am living in Sun City and am completely sold on Arizona.”

In June 1972, Arizona Highways featured an article with Joyce Rockwood’s byline. I imagine the sight of her own name was liberating. Living in a time when married women generally used their husbands’ last names, and given that she worked on articles and books with her husband, Joyce certainly felt pressure to use his name. In several books written or edited apart from Josef, she remains identified as Joyce Rockwood Muench.

While most of Joyce’s articles are accompanied by Josef’s images, a couple feature David’s. I wonder how often that happens — a magazine article by a mother and son. (I also wonder if, in that case, she wasn’t delighted the two did share a name.) I think of her as Joyce Rockwood, a writer separate from her husband no matter how many articles and books they did together, no matter how many years and adventures they shared.

Her Arizona Highways articles, and those for other publications, were the product of good research plus lived experience. If she wrote about a place, she went there. I’m certain she was never without local wildflower or tree books as she wrote about the Arizona desert, Arizona’s mountains, Marble Canyon, Glen Canyon, California’s Sierras and much of the Southwest. She and Josef spent a great deal of time on the Navajo Nation, and although her writing about the tribe is “of the time” — by which I mean that while she and Josef had real friends among the Navajo people, they also viewed them as exotic — it also is respectful and caring.

Because she and Josef were close friends with Harry and Mike Goulding, proprietors of a lodge and trading post in Monument Valley, they spent much time there. In the September 1960 issue of Arizona Highways, Joyce wrote a piece about an Arizona road trip that covered virtually the entire state — which by then she probably knew by heart, so much time had she and Josef spent there. But she wrote with a special fondness for Monument Valley, which had become a tribal park two years earlier. And it was Josef’s photos, shown to film director John Ford, that influenced Ford to use Monument Valley as the location for many Westerns.

Joyce, too, would have fit right in as a cast member in Ford’s films. “Friday I went bareback riding,” she wrote in her journal on October 10, 1926. “I had quite a time getting Druscilla to canter, but when she began, she went like the wind.”

Could anyone have a more perfect image of their mother-in-law?

Arizona Highways Inaugural Hall of Fame Inductees