Ross Santee

Writer and Artist

1888–1965

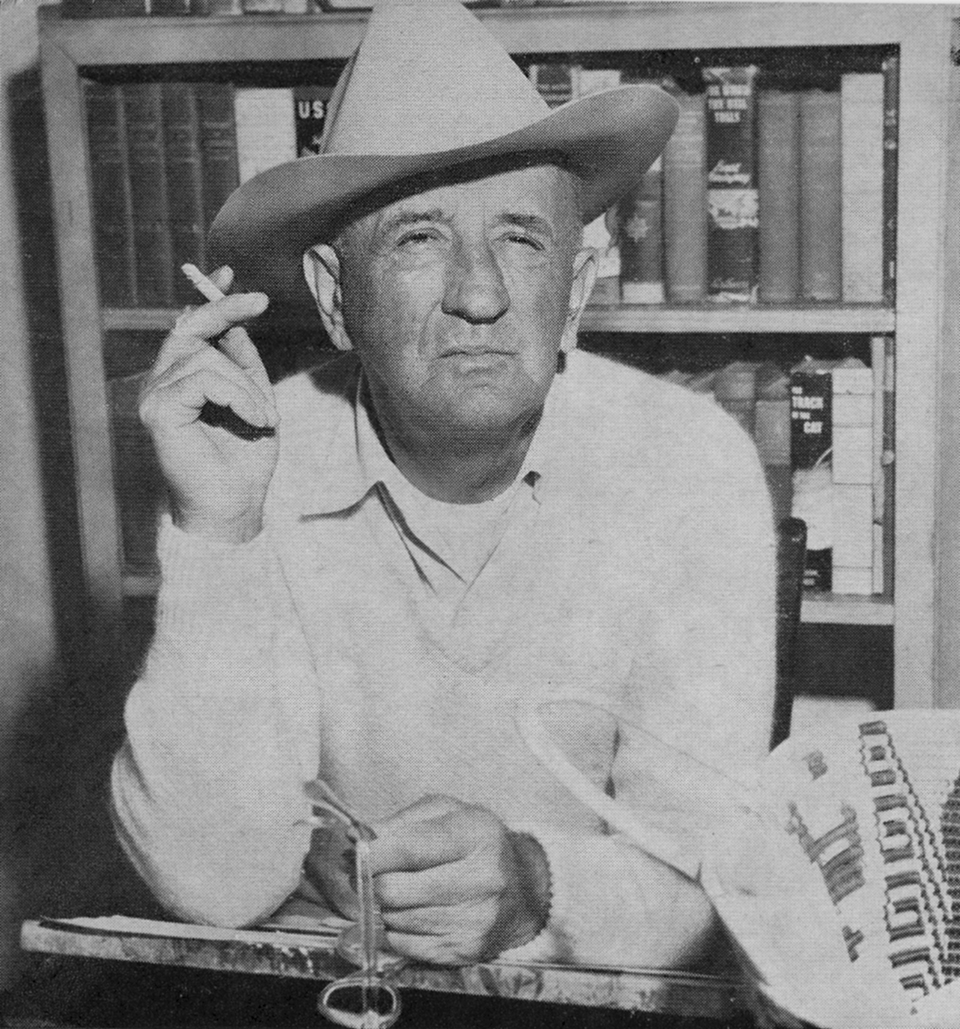

In a photo in a 1956 issue of Arizona Highways, longtime contributor Ross Santee leans forward, resting on his elbows. With a bookcase behind him, Santee squints as though scanning the horizon, cowboy hat characteristically tilted over his right eye, a curl of smoke rising from a hand-rolled Bull Durham cigarette.

At 6-foot-3 and 185 pounds, Santee embodied his nickname, “Slim.” One reporter described him as “sturdy as an oak, but gracious as a willow.” And like all great men, she observed, he was not readily recognized as such. “Most likely,” she wrote, “you’ll find him in the background somewhere.”

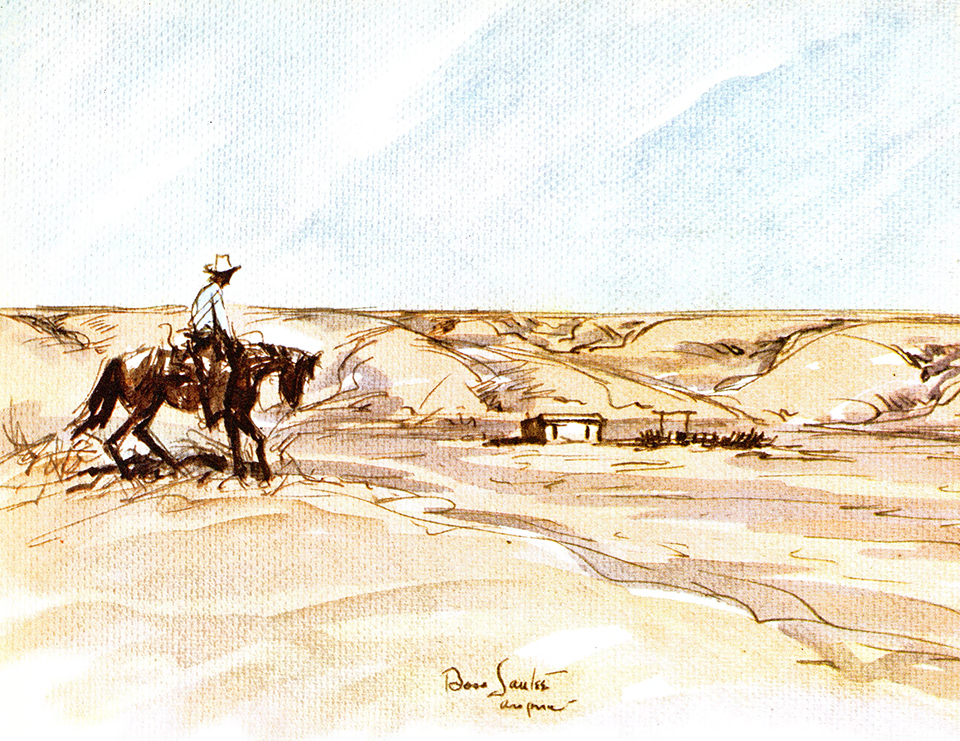

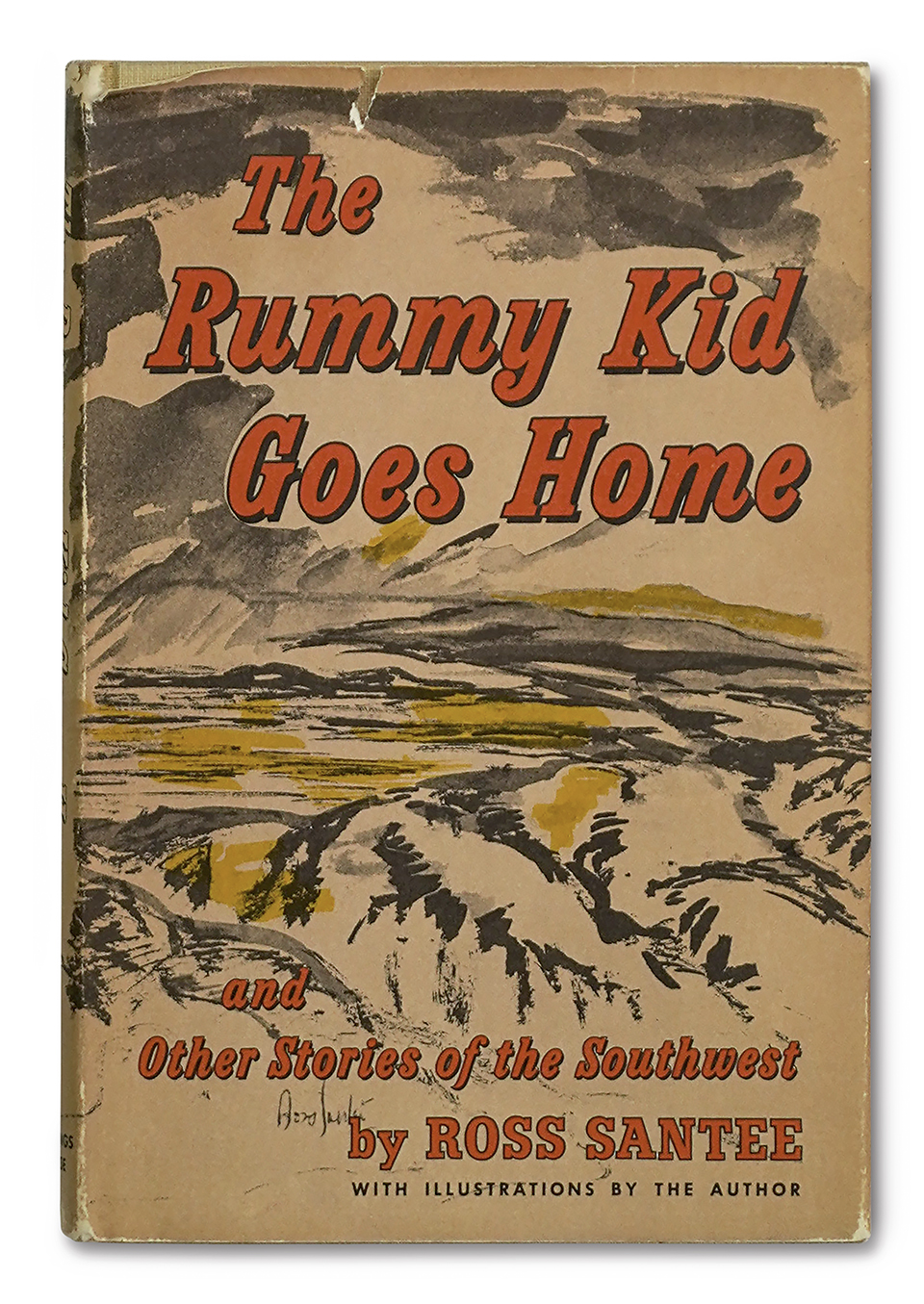

Among this magazine’s most notable contributors, Santee is part of a class of artists that includes Frederic Remington, Charles M. Russell and Maynard Dixon. But while his art was good enough to hang in the National Academy, it became secondary to his writing. The dozen books he penned included short story collections, novels, children’s books, nonfiction, a memoir and humor, and most of them were about cowboys, horses and the West. Reviewers have compared his novel Cowboy to Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. His short story Water, republished in Arizona Highways, won the O. Henry Award.

A Midwesterner by birth, Santee stumbled upon ranching and writing while aspiring to become a cartoonist. Yet he created some of the truest portraits of what he called “the West-That-Was.” And his contributions to Arizona Highways over nearly 30 years helped transform the magazine from what one commissioner called a “drab little journal of technical highway information” into an Arizona institution with an international reach.

Santee was born in 1888 to Quaker parents in the farming and ranching community of Thornburg, Iowa. Although he had no memory of his father, who died when he was 3, the town blacksmith told him “there was no horse he couldn’t ride or tame.”

Aside from requiring that he attend Methodist services on Sundays — Thornburg had no Quaker meeting houses — his mother left Santee free to pursue his interests, primarily hunting, sports and pool. While finishing high school in Moline, Illinois, Santee broke his nose playing football; later in life, the injury helped him appear to have been a lifelong cowboy.

But Santee also liked books, and he read everything Twain ever wrote. And although he failed art in high school — he recalled not being interested in “making copies of plants and flowers” — he liked to draw.

“Magazines were scarce in those days,” he wrote in his memoir, Dog Days. “At least, they were in our house. An’ about the only drawings I saw were John T. McCutcheon’s cartoons in the old Chicago Record. … His drawings interested me so much that when McCutcheon went over to the Tribune we switched along with him.”

About that time, Santee met his first “artist in the flesh,” a sign painter hired to do lettering on the local bank. It turned out, the painter knew McCutcheon, and he told Santee, “He makes a lot of money, too.”

“That settled it for me,” Santee wrote. “I’d be a cartoonist now for sure. For drawing pictures wasn’t work. An’ hard labor in any form had never appealed to me.”

While in Chicago to attend a football game, Santee wandered into the Chicago Art Institute and took in the student drawings that lined the hallways. “An’ when I found an original McCutcheon cartoon,” he wrote, “I knew I was going there to school.”

Santee paid for his first year’s tuition with traveler’s checks he won playing pool. “I thought three months would do the trick,” he recalled. “Maybe six.”

His first class began at 9 a.m. and lasted until noon, but at 11:30, he rushed off to his job in the cafeteria, which left him smelling like the day’s lunch. With characteristic humor, he wrote that a friend “finally quit because all the dogs followed him.”

Afternoon classes lasted until 4 p.m. Then, twice a week, Santee swept corridors and classrooms until 6. At 7, he headed for a job working backstage at a theater, which meant getting home around midnight.

Cartoon class met Fridays at 4 p.m. “We pinned our drawings on a line across the room, an’ the instructor criticized,” Santee recalled. “But most of the ideas we brought in had moss upon their backs.”

Like other students, Santee tried to imitate prominent cartoonists. “That was where I made my big mistake,” he said. “You can’t be someone else and get away with it.” He got fed up with cartoons — “hated the lousy things” — but didn’t have the nerve to admit he’d failed. After five years at the institute, he set out to make his fortune in New York and “damned near starved to death.” He added, “I knew my drawings were bad … for I wasn’t doing the thing I wanted to, an’ worst of all I didn’t know what that was.”

After a year, he’d had enough. Making a bonfire of his pencils, as one reporter put it, Santee vowed never to put pencil to paper again, except to sign a pay voucher. “I wanted to get as far away from pictures an’ people who drew them as I could,” he said. “So I took the first train West.”

Santee wrote about that trip in The West I Remember, first published in Arizona Highways in 1956. Western illustrations of the day featured close-ups of horses and cowboys, so Santee was unprepared for the vast expanses that rolled past his train window.

“The country itself dwarfed everything,” he wrote. “I couldn’t get enough of the big alkali flats or the mountains that appeared so close at hand and yet were many miles away.”

He found work wrangling horses at the Bar F Bar Ranch, near Globe. “It was a lonely job, but I liked it,” he wrote. “I wanted to be alone. For I’d failed in the thing I started out to do, an’ the less I saw of anyone, the better it suited me.”

He didn’t pick up a pencil for a year. Then, one day, he found himself sketching one of the horses on his chaps with a burned match. Eventually, he bought india ink and brushes and was making as many as 100 drawings a day. “An’ for the first time since I started off at school it was really fun again,” he recalled. “But each night before I took the horses in I built a fire an’ burned them up.”

About two years after arriving in Arizona, Santee included a sketch of the ranch foreman in a letter to an art school friend who worked at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. His friend showed it to his editor and wrote back to say the editor liked it and wanted more.

When the Post-Dispatch published his illustrations, Santee felt encouraged enough to return to New York, this time carrying sketches of things that interested him, done his way. After years of rejections, he got a friendly reception at Life magazine, where the editor who’d bought the first sketch he’d ever sold was working.

After Santee told the editor of another publication, Boys’ Life (now Scout Life), an anecdote about life on the ranch, the editor asked him to write it up. “Pictures cause me enough grief without taking on more misery,” he replied. But the editor insisted, then asked for another. And when an editor at Leslie’s Weekly asked if he’d published any writing, Santee said he’d just sold two lousy stories to a boys’ magazine. That editor “countered by asking me to bring him one of the lousy things,” Santee wrote.

Soon, the stories Santee was illustrating were his own, and he could afford to hang up his spurs. His success puzzled him. “Writing still comes hard to me, an’ I expect it always will,” he said. “The real fun in doing a story is drawing the pictures for it.”

It was the editor of The Red Book Magazine (later Redbook) who asked Santee to write a story about a drought, which became Water. The editor turned it down, finding it too unpleasant. So did almost every other editor in New York. Then Santee realized he hadn’t sent it to Collier’s, which published the story to great acclaim.

It’s not a coincidence that Santee married in 1926, the year his first book, Men and Horses, was published. His future wife, Eve, worked in a New York bookstore, and a friend had recommended the book. After a brief courtship, they married and built a home in Arden, Delaware, to be near an ailing family member. It remained Santee’s primary residence until Eve’s death in 1963, but they took frequent extended trips to Arizona.

From 1936 to 1941, the couple lived in Phoenix, where Santee served as state director of the Federal Writers’ Project — part of the New Deal-era Works Project Administration — and edited the Arizona State Guide. “For many of the kids on the project, it was their first job,” he wrote. One young writer recalled Santee had a flair for knocking “the gingerbread from a yarn.” Many of the project’s writers went on to have prominent newspaper careers.

“I really got more out of this project than anyone on it, I guess, because of the people I met and worked with,” Santee wrote. One of those was Arizona Highways Editor Raymond Carlson, who became one of Santee’s closest friends.

In 1936, Santee’s work began appearing regularly in the magazine, often accompanying stories credited to Federal Writers’ Project contributors. In the 1950s, Santee told a reporter the magazine was one of his favorite sketch outlets. “It isn’t like other magazines or newspapers that die tomorrow,” he said. “I’ve done a lot of work for that magazine, and I hope to do a lot more.” A decade later, he wrote to artist Philip C. Curtis: “Ray’s done quite a job with his magazine. … I don’t know how he survived all the pressures over the years.”

Curtis encouraged Santee to experiment with watercolor. “Phil also got me to paint in oil,” Santee recalled. “The damn medium had always had me buggered since it slipped an’ slid all over the canvas.” He figured out that by the time he’d smoked a cigarette, the paint would be dry enough to handle. “But,” he lamented, “I can still take pure color [and] make better mud out of it, I think, than anyone who ever tried the medium.”

Ted DeGrazia, another close friend, tried to get him to use a palette knife, but Santee couldn’t get a feel for it. “He was helpful in the fact that Ted uses simple colors,” Santee said. “Like myself, he gets confused if his palette is complicated.”

After Eve died, Santee returned to Globe. But less than two years later, in 1965, he died from a heart attack. A collection of stories he’d been compiling, all but two of them published in magazines years before, was published posthumously.

After Santee’s death, Carlson gathered a dozen of the cowboy’s closest friends on a knoll off State Route 77 south of Globe. On a trip to Safford, Santee had told Carlson he’d like to be cremated and have his ashes scattered there among the chaparral and mesquites.

Curtis and DeGrazia were there. So was Arizona Highways contributor Jo Baeza, whose book Ranch Wife Santee had illustrated, and Joseph Stacey, who later would succeed Carlson as editor. Each took turns scattering the ashes, which were mixed with rose petals.

A friend noted that Santee would have chuckled at the roses, adding, “Cow chips would have been more appreciated.”

Arizona Highways Inaugural Hall of Fame Inductees