Norman G. Wallace

Photographer

1885–1983

As soon as Norman G. Wallace arrived in Arizona Territory from his native Ohio in 1906, he fell in love with the landscape of what soon would become the 48th state. Fortunately for Arizona Highways, he channeled that affection into photographing the natural beauty, small towns, historic sites and just about everything else under the Arizona sun. And he blended his passion for photography with his career as a surveyor and civil engineer, a profession that took him to every corner of the Grand Canyon State with his camera by his side.

Wallace’s early surveying work sent him in many directions. From 1906 to 1931, he was employed as a draftsman and transitman for the Southern Pacific Railroad, surveying rail lines across the Southwest and northern Mexico. But after he was laid off by the railroad during the Great Depression, he took a new position with the Arizona Highway Department, a predecessor of today’s Arizona Department of Transportation, in 1932. He worked there as a transitman, surveyor and civil engineer; then, from 1943 to 1955, he served as Arizona’s chief location engineer. Throughout his 23 years with the Highway Department, he fundamentally shaped the state’s developing road network.

Soon after his hiring, he paved the way for modernizing Route 66. In later years, he lived in isolated tent camps around the state as he and his survey crews located and improved dozens of Arizona’s signature highways. He would spend weeks away from his wife, Henrietta (whom he married in 1934), roughing it in the state’s rugged backcountry. Wallace loved the work, spending days in out-of-the-way places with a motley crew of chain men, rod men, levelers, brush cutters and a cook. Recalling those years, Henrietta estimated her husband had camped in more than three dozen spots around the state as he surveyed Arizona’s modern highway network into existence.

Many of Wallace’s major surveying accomplishments with the Highway Department remain with us today. In addition to the improvements he supervised along Route 66, he located and modernized stretches of U.S. routes 60, 70 and 80 in the central and southern portions of the state. Arizona’s rugged canyons and mountains were constant challenges but rarely discouraged him. He helped modernize present-day State Route 64, along the Grand Canyon’s South Rim; the Apache Trail (State Route 88), east of Phoenix; and the Coronado Trail (present-day U.S. Route 191), through the White Mountains. And he was especially proud of his work along the Black Canyon Highway (later Interstate 17), which eventually forged a high-speed link between Phoenix and Flagstaff.

Through all these expeditions, Wallace’s camera was by his side, and he made thousands of pictures that recorded both his highway projects and the wider Arizona landscape he deeply cherished. When he wasn’t working, he would take “picture trips” on his days off or enjoy longer excursions with a camping buddy or two to explore some corner of the state he wanted to see and photograph. And within a year of Wallace’s hiring, his superiors at the Highway Department began to use his photographs in the department’s signature magazine, Arizona Highways.

Some of Wallace’s pictures in the magazine documented state-funded work on highways, but increasingly, his images of desert vistas, cactuses, sweeping cloudscapes, mining towns and historic sites promoted a broader vision of Arizona’s character and beauty. Indeed, Wallace’s published work in the magazine between 1932 and 1955 — photographs, as well as dozens of articles he authored — helped transform Arizona Highways from a technical publication focused on road and bridge building into the state’s flagship promotional periodical, one that reached millions of appreciative readers in the United States and beyond.

Wallace’s love of photography had begun early in life. His father, an accountant in Cincinnati, dabbled in picture taking, and young Wallace picked up the hobby. When he arrived in Arizona, he had a simple Kodak box camera, but in later years, he acquired more sophisticated equipment. At various points in his career, he owned a large-format 8x10 bellows camera, a 5x7 Graflex, a medium-format Zeiss Ikon Ikonta and a Ranca miniature camera, which he used for making color exposures beginning in the late 1930s.

Wallace readily embraced color photography, a skill that served him well in polychromatic Arizona and in his work for Arizona Highways. He was especially proud of producing a photograph of lower Oak Creek Canyon that would be the first color photograph to appear on the cover (July 1938). Henrietta even endured his photographic passions on their honeymoon, when he spent hours photographing the Grand Canyon — a trip that produced a future cover photo and story for the magazine (January 1935). As she lamented, “He was married to his cameras before he was married to me,” and much of that romance continued in later years. But she grew to accept Wallace’s desire for careful image making and patiently endured his lengthy roadside stops to capture just the right scene.

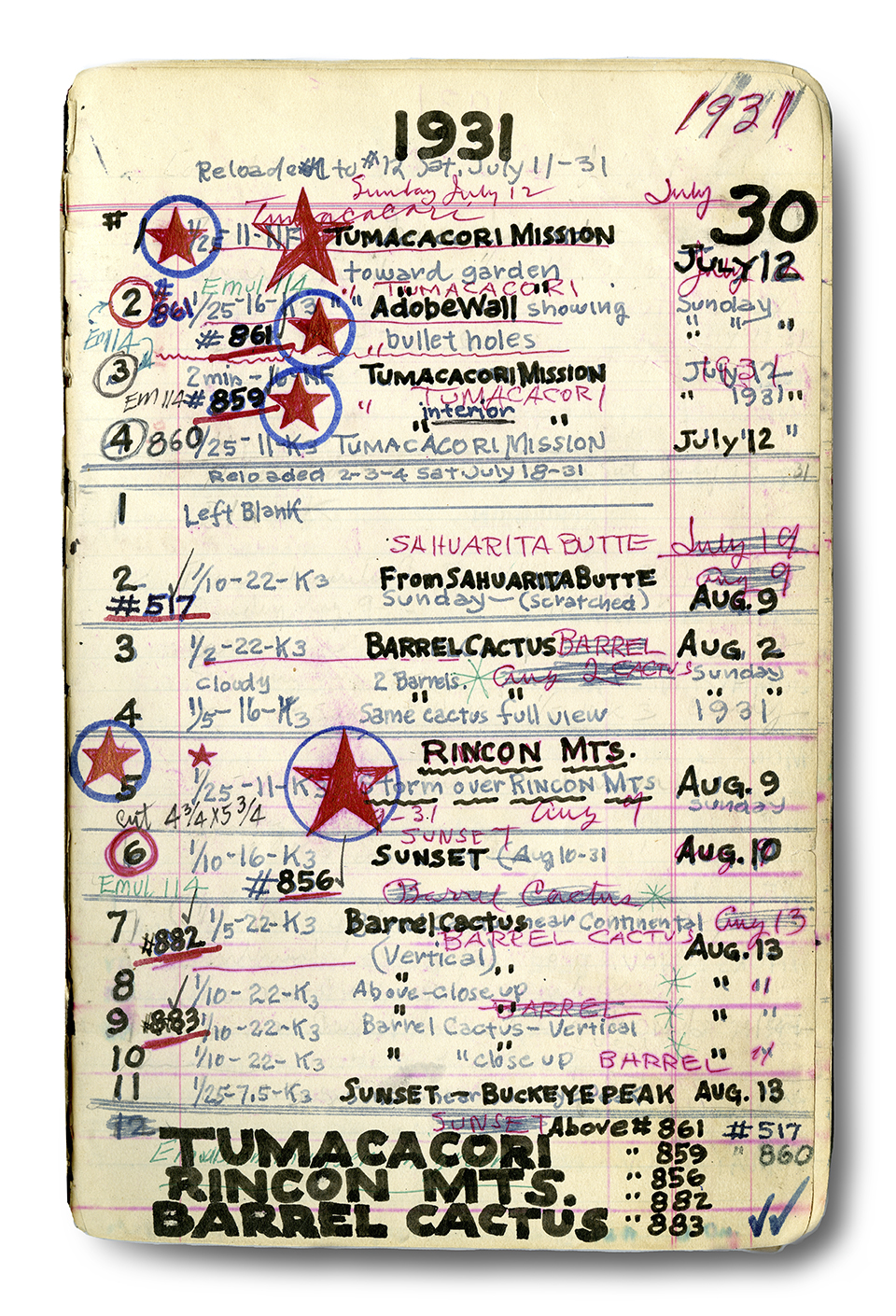

Wallace’s voluminous logbooks meticulously documented his photographic adventures. In more than 1,400 pages of detailed notes spanning many decades of picture taking, he noted the precise location and circumstances of thousands of exposures as he took them. Both his work-related images (“state pictures”) and his personal photographs (“art pictures”) were noted in the logbooks, and many were later annotated with bold stars (for a good shot) or complaints about “bad luck” or “blurred prints.” His daily dose of logbook entries would often include humorous commentary, such as the time he was camped north of Cameron on a chilly night beneath the stars at the “Hotel de Wallace.”

Wallace embraced diverse subject matter in his photographs and stories. Arizona’s natural landscape was vastly different from that of his native Midwest, and he learned the Latin names for desert cactuses and when and where yuccas and ocotillos would be in bloom. Many of his short, illustrated articles in the magazine focused on nature and carried headlines such as Storm in the Arizona Desert (October 1935), It’s Springtime in the Desert (May 1936) and Snow! Strange Sights Greet Arizonans (February 1937). In his personal collection of images, he had files labeled “Cactus Plants,” “Cloud Effects,” “Superstition Mountains” and “Wild Animals,” among other subjects.

He shared a similar passion for history, and ancient Puebloan settlements, Hispanic churches and Territorial forts always caught his eye. Predictably, his fascination with the past was captured through the lens of landscapes. Wallace often visited the windswept ruins of Wupatki National Monument, established in 1924, and loved camping there, sketching and photographing the surviving brick walls and towers. He also was drawn to Mission San Xavier del Bac, not far from his home base in Tucson; he visited dozens of times, and his shot of the church was featured on an early cover of Arizona Highways (December 1932). He also published an article on the Native history and scenery of Canyon de Chelly (Canyons of Death, November 1936).

One of Wallace’s favorite historical adventures, though, was following in the footsteps of Lieutenant Edward Beale’s federally funded wagon-road survey across present-day Northern Arizona in 1857. Memorably, Beale’s explorations featured two dozen African camels that carried the expedition’s equipment and provisions. Wallace delighted in rereading Beale’s journals, following the precise route of his journey and photographing the scenes along the way. In Arizona Highways, he published his detailed narrative of the trip, The Trail of the Camels, in October 1934.

The highways that Wallace modernized became leading characters in his photography and writing. He had an aesthetic attraction to a beautiful road — Henrietta recalled that he loved to take “a picture of a road that was always curving” and that she knew when and where he would stop along a highway. As his archive grew, he organized hundreds of his images by highway number, making it easy to find them and use them in his work. For Wallace, a highway was a story that unfolded across the Arizona landscape, taking travelers up and over spectacular grades, across rugged terrain, and through mining towns and desert scenery.

Some of Wallace’s best photographs and articles that appeared in Arizona Highways literally featured Arizona’s highways, and they were powerful promotional pieces that celebrated the state’s good roads and all they traversed. In one of his last contributions to the magazine, in May 1955, he penned a lengthy piece on one of his most beloved roads: Arizona 66: The Scenic Wonderland Highway. The essay follows Route 66 from east to west as it crosses Navajoland (“most of the terrain will be of the wide-open spaces type”), summits the pine-studded Coconino Plateau near Flagstaff (the “finest part” of the state) and descends toward the Colorado River (the “vastness of the desert regions of Western Arizona”). It was a captivating journey Wallace had taken countless times as he worked to modernize the Mother Road.

Wallace and Henrietta moved from Tucson to Phoenix in 1950, and Wallace retired from the Highway Department in 1955, at age 70. The couple witnessed the extraordinary expansion of the Valley of the Sun that saw Phoenix’s population grow from 100,000 in 1950 to 800,000 in 1980. Wallace spent his retirement organizing his photographs before donating a large collection to the state in 1968. His work was later honored in a display at the state Capitol in 1976.

He kept making photos, too — taking short trips around the state, revisiting familiar spots and favoring Ektachrome color slide film. There were pictures of Arizona scenery, special bridges and overpasses, and more intimate local portraits of a sunset at the house or a neighbor’s flower garden. Wallace remained engaged with the visual scene in these later images, but that world was shrinking — a far cry from his earlier, far-flung adventures.

Wallace died in Phoenix in 1983, at age 98, and Henrietta gave many of his remaining photographs to the Arizona Historical Society in 1984. The collection grew larger thanks to donations from Arizona Highways in 1999, and today, Wallace’s legacy is preserved in the Norman G. Wallace Photograph Collection at the AHS in Tucson. Occupying 55 boxes of material, the collection celebrates Wallace’s prolific photographic talents, his long career creating Arizona’s highways and the visual treasures of a state he dearly loved.

• William Wyckoff is the author of Riding Shotgun With Norman Wallace: Rephotographing the Arizona Landscape (University of New Mexico Press, 2020).

Arizona Highways Inaugural Hall of Fame Inductees