Red dust eddies across U.S. Route 191 as my buddy Tom Gamache and I wheel past the low-slung sandstone mesas that extend off the Lukachukai Mountains. There are roadside rodeo rings and hand-painted signs touting revival meetings in a big, empty country, where flocks of sheep graze and the gusting wind ripples through expanses orange with blooming globemallows.

Pulling into historic Teec Nos Pos Trading Post, we’re still in Arizona, if barely — five minutes from the Four Corners and 100 miles closer to Santa Fe, New Mexico, than to Phoenix. Ute Peak looms in Southwestern Colorado, while the dark mass of Mesa Verde and the snow-capped San Juan Mountains skyline rise to the east.

We’re out looking for Arizona’s last trading posts, and Teec Nos Pos is the real deal: a traditional business oriented to the local community, just as it has been since 1905. A propane-storage tower rises above a building topped by a corrugated roof and adorned with murals of Geronimo and other Native American icons. The canopy shading the gas pumps reads, in Navajo, Ahe Hee Hagoonee, with the English translation, “Thank You, Have a Good Day,” just beneath it.

Inside the general store, skeins of yarn destined for weavings dangle over John Wayne puzzles, and a kachina figure stands above boxes of Hamburger Helper. A side room displays premium Navajo blankets, jewelry and baskets that can be had for a fraction of what you’d pay in Scottsdale.

store building, which was erected shortly after World War I. | Mark Lipczynski

It’s no Circle K: A woman and her father deliver 71 pounds of mohair from their Sanostee, New Mexico, herd of Angora goats, and a medicine man out of Kayenta carries a ceremonial hand-tanned deer hide for trader John McCulloch to purchase.

“Tanning is a dying art; you can see the difference,” says McCulloch, who has run the post since 1994. He and his then-wife, Kathy Foutz, whose family operated Teec Nos Pos and other trading posts for generations, took over then, and McCulloch continued to run the operation after he and Foutz divorced. “And they want a hide with no bullet holes, but with the ears, tail and all four hooves, if possible. From an animal that died a natural death, or maybe been hit by a car. Not shot. So a big, beautiful hide with no holes can fetch the better part of $1,000.”

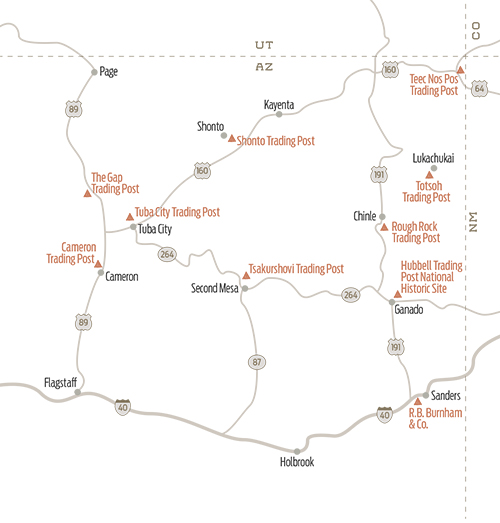

Not many authentic trading posts survive. Big-box stores in what the Navajos and Hopis call the border towns — Flagstaff and Winslow in Arizona, and Gallup and Farmington in New Mexico — greater mobility and the decline of the sheep trade have led to the virtual demise of the 140-year-old trading post system. Preserved as a national historic site, Hubbell Trading Post still operates. But most others have been converted into convenience stores. Or simply abandoned.

Running a trading post is both a business and a calling. Covering one wall in McCulloch’s office are rows of handwritten bills of sale recording loans he has doled out.

“There’s a drawer all full of them, too — probably half of them are uncollectable — and a filing cabinet where the top drawer is just dead loans,” he says. “It changes your perspective on money. You can’t mind losing a bit, because you’re going to. I know guys who sold out a post with $200,000 in uncollectable loans on the books. It accumulates over the years. But when you divide by 30 or 40 years, it’s not such a big deal.”

Even so, McCulloch is no easy touch. Wearing a pale, blue-checked shirt and white straw Larry Mahan cowboy hat, he walks through the post, fielding questions from staffers and customers. An employee hands him a phone: Someone in New Mexico wants to cash a check. “Who’s it from?” asks McCulloch. “Oh, your boss. Well, who’s your boss? Mickey Mouse, or Donald Trump?”

That hint of impatience notwithstanding, McCulloch speaks softly and respectfully with those at the post. Lula Tom, a weaver from Sweetwater, and her husband, Ranson, want to show McCulloch the rug she just completed. McCulloch flatters her — he’s off by a full 10 years when he guesses Tom’s age — before the staccato negotiation begins. He knows her weaving, and she holds up the 20-by-30-inch rug, done in the distinctive Teec Nos Pos style.

“So, how much you want?”

Tom coyly shifts back and forth, then smiles. “$550.”

“I can go to $300.”

“$350.” Done deal.

We slip into New Mexico, then back into Arizona along Indian Route 13, traveling through 8,441-foot Buffalo Pass in the Chuska Mountains, before dropping into Lukachukai. Stray dogs, seemingly assembled from mismatched parts, laze outside the orange cinder block Totsoh Trading Post. The gas pumps are long gone from the island out front. There’s the usual convenience-store fare, energy drinks and the like, but also lamb and calf formula, infant cradle boards and sacks of Blue Bird Flour, the go-to brand for fry bread.

Hank Blair has owned Totsoh with his Navajo wife, Vicki, since 1984. Four generations of family come into and out of the office as he waits for his new grocery distributor’s truck, now running way late. Blair’s father and brothers all worked in the trading post business, and his mother taught at the boarding school in Teec Nos Pos. He mostly grew up at Red Mesa Trading Post, where his mother home-schooled him back in the days when business was all trade and barter. Sheep provided the foundation for the economy: The Navajos paid their tabs with wool in spring and lambs in fall.

Then, in 1965, with the Beach Boys all the rage, Blair decided to become a surfer. Transitioning from Kayenta to “Cowabunga!” proved trickier than he anticipated. Blair discovered California water was cold and surfboards were heavy. “You can also drown,” he adds.

After serving in Vietnam, Blair resumed the trading post life. Rug weavers still sheared their own sheep, then cleaned, dyed, carded and spun the wool. “Used to take a month to prepare the wool,” he says. “Now, weavers just buy the wool. There are maybe a third of the sheep that there used to be. The wool market has gone all to heck.”

Another change came a few years ago, when the federal government stopped issuing checks and instead went to direct deposit and debit cards. Blair’s daughter, Cheryl, says until then, it was always an event when checks arrived. “I remember down there, oh, my gosh, the whole half of the store would be full of nothing but people for two hours,” she says. “Talking. Gossip. The latest news. It was a big gathering to come to the store and wait for your check. That’s completely stopped.”

Blair looks at the business with a mix of stoicism and humor. “I’m too dumb to know how to do anything else,” he says. “I make enough money to live, but not enough to leave.”

His daughter suggests there’s more to it than that: “People have known Dad from Kayenta to Chinle. He’s actually part of something that’s bigger. He’s a trader. It’s in our blood.”

We drive two hours south to Sanders off Interstate 40, where, for going on 50 years, Bruce Burnham has operated R.B. Burnham & Co. with his wife, Virginia, a silversmith and goldsmith who grew up on tribal land. Wearing a bola tie and a black shirt stitched with his name in script, Burnham greets us in the wareroom, the showcase for the rugs, baskets and jewelry the couple has amassed over the decades.

Burnham is a fourth-generation trader. In the 1880s, his ancestors were Utah polygamists, but when the Mormon church and the federal government sought to ban the practice, his great-grandfather and great-uncle left Salt Lake City, probably bound for Mexico. They settled in New Mexico, where his great-grandfather drove a trading wagon pulled by up to eight horses. He would start in Colorado with a load of lumber, then trade for supplies as he traveled the Navajo Nation, stopping to see three wives living in different towns along the route. Eventually, every trading post in the northeastern part of Navajoland belonged to a Burnham or family in-laws.

“I spent the first five years of my life on the Navajo Reservation, and everybody I associated with was Navajo,” Burnham says. “I felt at home with them. I thought there weren’t very many white people and was shocked when we moved to town for my sister and I to go to school, then found it full of white kids.”

Burnham didn’t plan on the trader’s life. But while driving a Coca-Cola delivery truck after leaving the Army, he stopped at Shiprock Trading Post. “I could smell the sheep pelts and the kerosene splashed on the floor. The Blue Bird Flour and the mutton fat from the meat we sell,” he says. “What lured me back was all of those odors that I hadn’t really smelled in 10 or 12 years. Hit me hard. Hard enough that I walked right in and applied for a job. That was where it all began again for me.”

He worked at Red Valley Trading Post back toward Lukachukai, but in 1965, worried that the world was passing him by, Burnham left Arizona. Like Blair and McCulloch (who worked at a high-end pawn shop in Beverly Hills), he moved to California, landing in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district. “It was raging then. Beatniks galore,” he says. “Finally I decided that wasn’t for me and came back home.”

Burnham’s post is among the few that still accept pawn, the longtime bartering and banking practice in which customers can trade crafts and valuables for cash loans. Pawn has always offered Navajos a way to get small sums unavailable from conventional financial institutions, particularly between shearing and lamb season, when they earn no income.

Pawn is prohibited on tribal land, but Burnham’s post sits on private property adjacent to the Navajo Nation. He unlocks the door to his pawn room, where rugs and buckskins stored in paper bags stack up on shelves and jewelry in sealed plastic bags hangs on the walls. He estimates the room holds up to 2,000 pieces.

The trader’s hope, Burnham says, isn’t to sell the item when someone fails to repay the loan on time. Traders actually want to avoid selling off what they call “dead pawn,” because it can violate a well-meaning customer’s trust. Plus, a rug or basket has greater value when pawned repeatedly than it does in a one-time sale to a tourist.

Even so, corrupt traders sometimes abused the system, and pawn came under fire in the 1960s and ’70s. New regulations dramatically changed the business, cutting into trader profits. Many posts shut down or reopened in border towns, especially in New Mexico.

Burnham says he has to keep innovating. He and his daughter, Sheri, attended auctioneer school and now conduct rug auctions at such institutions as the Museum of Northern Arizona. With the closure of so many posts, weavers lost access to markets. The few remaining posts couldn’t sell all the rugs being made, so now the auctions take the weavers’ work to their best customers. Burnham recently auctioned $129,000 worth of rugs, with 80 percent of the take going to weavers. “The everyday person has to put a loaf of bread on the table. That’s who we want to help,” Burnham says.

He adds: “I’ll admit it’s an ego thing in a lot of ways. Someone asked me, ‘How come you’ve stayed here so long?’ And I said, ‘Because when I’m here, I’m somebody.’ I’m the kingpin. I’m really somebody. If I’m in town, I’m just another guy that dropped out of high school. Out here, I’m somebody. They look up to me; they respect me. We have a mutual respect and a caring relationship. That’s what’s fed me all these years.”

Fast-moving clouds shadow Keams Canyon as we work our way west, along State Route 264, to see Joseph and Janice Day at their Tsakurshovi Trading Post on the Hopi Tribe’s Second Mesa. We find Joseph outside, next to his pickup, which is encrusted with red mud after he dug it in while checking his corn and bean fields.

When Joseph moved to the Navajo Nation from Kansas in 1965, the traditional ways prevailed among what he describes as the “long-hair-wearing, hogan-living, sheepherding, Navajo-speaking, National Geographic Indians” he met. After answering a newspaper ad in the early 1980s, the couple started running Sunrise Trading Post at Leupp. The Days read letters to the locals and wrote letters for them, too. They bought and sold livestock and hay, and many customers signed the credit book with a thumbprint. Sometimes the Days even prepared tax returns. The couple loved their work. As for the post’s manager?

“He treated everybody like they were over on their credit limit and wanted 20 bucks to go to Winslow and get drunk, you know? And you don’t have to treat people like that,” Joseph says. “I mean, there were some people, for sure, that was true. But most of ’em weren’t. The Navajos hated him, and we finally quit. I could have worked there forever if it weren’t for him.”

The Days opened up their own shop in 1987, operating out of an 8-by-16-foot shack while living in the old trailer behind it. They didn’t sell groceries, but, Joseph says, “We like to call ourselves the last of the old-time trading posts, even though we’re only 30 years old.”

While the fine collection of kachinas draws outsiders, the business focuses on Hopis and other Native American customers. The Days stock cottonwood root and mineral pigments for kachina carvers. There are fox skins and buckskins, deer hooves and turtle shells, as well as gourds for rattles and Hopi ceremonial textiles. Ninety percent of the baskets go to locals, who use them as a medium of exchange to pay for weddings and as prizes in ceremonial races.

Thanks to what Joseph calls “the Moccasin Telegraph,” customers from far beyond the Hopi mesas find the store, from a war chief from Jemez Pueblo looking for pigments to a couple of Apaches up from San Carlos needing buckskins.

After a lunch of green chile pozole, Janice comes in and out, showing Joseph kachinas that carvers want to sell. The Days help keep alive a timeless Southwestern trading tradition, but though some of the old ways endure, Joseph has few illusions that things won’t continue to change.

“Tell you a story,” he says. “Old Navajo man walks in. Face like a wrinkled-up brown paper bag. Old man. Real old. He’s got what must have been his great-granddaughter interpreting for him. He’s looking for moccasins. We got the pair he needs. We got his size. He’s standing there. A little short guy. He reaches into his jeans, and we know he’s going to pull out, in traditional Navajo style, a wrinkled-up $100 bill. Dude pulls out his debit card.

“You know what happened to trading posts? The late 20th and early 21st century happened to trading posts.”